|

|

| J Eng Teach Movie Media > Volume 24(2); 2023 > Article |

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of employing the metaverse platform Gather for shadowing practice using TED Talks, focusing on the development of oral proficiency and affective attitudes among Korean EFL learners. A total of 49 college students participated, divided into two experimental groups. Group 1 (n = 24) engaged in shadowing practice on Gather, while group 2 (n = 25) partook in the same shadowing activities in a traditional classroom. Data collection involved pre- and post-speaking tasks and pre- and post-questionnaires assessing affective attitudes. The results revealed significant improvements in speaking skills for both groups, with group 1 demonstrating a higher degree of effectiveness. Furthermore, participants in both groups exhibited increased interest, motivation, and confidence levels. However, a notable difference emerged in anxiety levels, as the students in group one displayed a significant decrease in speaking anxiety, while those in group two showed no improvement in speaking anxiety after participating in the study. The findings indicate that integrating Gather for shadowing practice can effectively enhance Korean EFL learners’ oral proficiency and positively influence their affective attitudes toward language learning. The study contributes to the growing body of research on the potential of metaverse platforms as alternative learning environments for language instruction.

Language learning in the digital era has undergone significant transformations due to the emergence of cuttingedge technologies and platforms, which hold the potential to redefine language teaching and learning practices. One such platform gaining notable attention is the metaverse, a platform that provides immersive and interactive learning experiences for users. The term “metaverse” denotes a space where virtual and real worlds converge and interact, originating from the combination of the words “meta” and “universe” (Acceleration Studies Foundation (ASF), 2006). The metaverse offers considerable advantages as an educational domain, empowering learners to express their selfidentity through avatars and fostering an immersive environment that encourages active participation and interaction, aspects that may be lacking in other online platforms (Lee & Choi, 2022). In terms of foreign language acquisition, the metaverse is expected to demonstrate significant potential by facilitating an integrated learning setting that supports interactive communication and collaboration within a virtual reality that resembles the real world (Jang, 2021; Lee & Ahn, 2022). Importantly, metaverse-enhanced instruction differentiates itself from alternative online platforms by enabling learners to make social connections and engage in meaningful communication and collaboration (Lee & Ahn, 2022). In addition, the use of the metaverse in education overcomes the limitations of traditional face-to-face classrooms, providing learners with immersive and realistic experiences that broaden their experiences and strengthen their future core competencies (Lee et al., 2022). Thus, the metaverse has significant educational value in terms of diversifying learning methodologies.

Such a learning environment is particularly beneficial for courses focusing on the development of speaking skills. Lee and Ahn (2022) suggested that metaverse platforms could be effective for English speaking courses, which require active and dynamic learner participation. The metaverse platform is expected for its ability to provide language learners with an authentic and engaging speaking experience, facilitating real-time interactions with peers and intensifying immersion. However, empirical research examining the efficacy of metaverse platforms in improving L2 speaking proficiency and their impact on learners’ affective factors remains limited. Consequently, this study aims to address this research gap by investigating the impact of the metaverse platform on EFL learners’ speaking proficiency and affective factors in English speaking instruction.

This study utilized Gather, one of the most user-friendly and educationally useful metaverse platforms, to conduct English speaking classes in a virtual world that is implemented similarly to the real world, presenting learners with realistic tasks to increase their engagement and facilitate interactions with other learner avatars. Gather offers a distinctive and interactive environment for language learning, allowing users to create customizable virtual spaces and engage in real-time communication with others. In this study, shadowing activities were selected for speaking practice to integrate metaverse-based interactions with shadowing techniques. During the shadowing process, learners can utilize the Gather platform to engage in real-time interactions and practice sessions with their peers, offering further opportunities for communication and immediate feedback. By merging shadowing techniques with the interactive features of the metaverse platform, learners can benefit from both the proven effectiveness of shadowing in enhancing speaking proficiency (Kim, 2018; Lee et al., 2010; Park, 2013) and the dynamic, interactive environment provided by Gather. Shadowing, a method in which learners listen to and simultaneously repeat native speaker speech, has been widely acknowledged as an effective means of improving language learners’ listening and speaking skills (Kim, 2018; Park, 2013). This technique allows learners to become familiar with the speed, pronunciation, and intonation of the target language, resulting in improved overall oral proficiency. By incorporating shadowing activities into the metaverse platform, learners can actively engage with each other and practice speaking in a highly interactive and supportive environment.

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on metaverse-assisted language learning by examining the effectiveness of the Gather platform in comparison to traditional classroom settings for English speaking practice. It investigates the impact of shadowing practice using TED Talks on the Gather metaverse platform on affective factors and the development of oral proficiency among EFL learners. TED Talks, engaging presentations featuring experts from various fields sharing their ideas, insights, and experiences, serve as an ideal source of authentic language input for shadowing practice due to their diverse range of topics and captivating content. In summary, this study seeks to bridge the research gap in the current literature on metaverse-assisted language learning by exploring the impact of shadowing practice using TED Talks on the Gather metaverse platform on EFL learners’ affective factors and oral proficiency development. The findings are anticipated to provide valuable insights and evidence to the field of language education, supporting the effective integration of metaverse platforms in L2 speaking instruction.

Shadowing activities have emerged as an effective technique for improving speaking proficiency among EFL learners. The shadowing method involves learners listening to and simultaneously repeating audio input in the target language, which can be from various sources, such as audio recordings, videos, or even native speakers. This method encourages learners to focus on the rhythm, intonation, and pronunciation of the language while also enhancing their listening and speaking skills. Park (2013) suggests that the shadowing learning technique has a positive impact on language learning by facilitating English sentence pattern learning, adaptation to native English pronunciation and pace, acquisition of natural stress and intonation, and motivation for English listening and speaking. Ryu (2010) also supports shadowing, stating that it can improve prosody, pronunciation, syntactical thinking, listening comprehension, reading and speaking speed, as well as vocabulary and idiom memorization. Additionally, shadowing enables learners to self-evaluate and improve their speech, without the need for teacher feedback (Kim, 2018).

Shadowing activities offer numerous benefits for EFL learners in terms of speaking proficiency development. First, these activities provide learners with a structured and focused approach to practicing their speaking skills, enabling them to concentrate on specific aspects of language production, such as pronunciation, intonation, and rhythm. This targeted practice can lead to significant improvements in speaking proficiency over time. Second, shadowing activities promote active listening, as learners need to closely attend to the input in order to repeat it accurately (Chung, 2010). This heightened attention to the input can enhance learners’ listening skills, which are critical for effective communication in the target language. Finally, shadowing activities can boost learners’ confidence in their speaking abilities (Chung, 2010; Kim, 2018), as the practice of repeating native speaker input allows them to become more familiar with the target language’s natural speech patterns. This increased familiarity can make learners feel more comfortable and competent when speaking in the target language, leading to more effective and efficient language learning.

Several studies have examined the effectiveness of shadowing activities for improving spoken language abilities in EFL learning contexts (e.g., Amoli & Ghanbari, 2013; Jin, 2022; Kim, 2013; Kim, 2018; Lee et al., 2010). Recently, Jin (2022) conducted a study that revealed the effectiveness of movie-shadowing activities for improving the speaking skills of EFL students. The study found that movie-shadowing activities were more effective than traditional English classes, particularly for students with low to intermediate English proficiency levels. Moreover, the results indicated that movie-shadowing activities had a positive impact on students’ interest, confidence, and motivation towards learning English. Similarly, Kim (2018) investigated the impact of movie-shadowing on listening and speaking abilities in English and found that it had a significant positive impact on speaking ability, but not on listening ability. In general, the study recommends movie-shadowing as an effective approach to enhancing EFL students’ English speaking skills and attitudes. In addition, Lee et al. (2010) conducted a study to examine the effect of shadowing activities on listening, speaking, and self-directed learning abilities among middle school English learners. The results showed that shadowing was more effective than traditional learning methods in improving listening and speaking abilities, particularly in improving phonological and sub-phonemic aspects. Furthermore, self-directed shadowing was more effective than traditional shadowing in enhancing listening and speaking abilities. Similarly, Kim (2013) found that shadowing had a positive effect on speaking ability, especially in fluency and pronunciation, but did not show significant improvement in listening ability among sixth-grade elementary school students. Amoli and Ghanbari (2013) also provided empirical evidence supporting the positive impact of shadowing activities on EFL learners’ oral performance based on accuracy, emphasizing the importance of this technique in enhancing learners’ language skills.

Overall, these reviewed studies provide empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of shadowing activities for enhancing EFL learners’ speaking proficiency and attitudes towards English learning, highlighting the importance of this technique as a valuable tool for L2 speaking practice.

In recent years, metaverse platforms have gained popularity in language learning due to their ability to provide immersive and interactive experiences. These environments offer unique opportunities for learners to practice their language skills in realistic contexts, interact with other learners or native speakers, and access a wide range of multimedia resources that can support their learning. Compared to traditional classrooms, metaverse platforms provide increased motivation and engagement, enhanced learner autonomy, access to authentic language input and resources, and opportunities for real-time interaction and feedback (Jeong et al., 2021; D. K. Lee et al., 2022; S. M. Lee & Ahn, 2022). Learners can participate in interactive activities, collaborate with peers, and explore new virtual spaces at their own pace and in their preferred settings, leading to more personalized and targeted language practice (Choi, 2022; Lee & Kim, 2020). Furthermore, metaverse platforms facilitate real-time communication and interaction among learners and instructors, enabling immediate feedback and opportunities for collaboration.

Apart from these advantages, metaverse platforms have the potential to significantly impact the development of speaking proficiency in language learners. They can provide learners with ample opportunities for speaking practice, which can lead to increased fluency over time (Lee & Ahn, 2022; Lee et al., 2022). In addition, learners can develop their ability to speak more naturally and spontaneously by engaging in real-time conversations with peers or native speakers. Moreover, virtual environments can expose learners to a wide range of vocabulary in context, allowing them to learn new words and expressions through authentic communication and multimedia resources. These benefits can contribute to more effective and efficient language learning outcomes, making metaverse platforms a valuable alternative to traditional classroom settings.

So far, there is limited research that utilizes metaverse platforms for EFL speaking instruction. Some studies have focused on using metaverse platforms for L2 speaking instruction, such as those conducted by Lim (2022) and Lee and Ahn (2022). Lee and Ahn (2022) conducted two sessions of English speaking activities using Gather with middle school EFL learners and found that metaverse-based education had positive effects on learners, including high satisfaction with the learning experience, increased interest in learning, and active participation. The study also revealed that interactions among learners and between learners and teachers were smooth and effective in metaversebased classes, suggesting that metaverses offer numerous benefits for English speaking classes, such as enhancing learners’ motivation and confidence. Lim (2022) conducted five Gather-based English discussion activities for college EFL learners and found that learners had an overall positive perception of metaverse-based education, which positively impacted their interest in learning and motivation. They also reported that communication with peers and teachers in the virtual space of Gather was easy and free-flowing. Lim (2022) proposed that metaverses could be used to enhance interaction among peers and teachers in classes that combine face-to-face and online instruction.

There is currently a scarcity of empirical studies that have examined the efficacy of metaverse platforms for improving L2 speaking proficiency among EFL learners and provided empirical evidence of its effectiveness. The majority of previous studies have been relatively short-term experiments, thereby necessitating a more comprehensive investigation of the development of learners’ speaking proficiency in metaverse-based English speaking classes, along with an extended experimental period. Such an investigation would yield empirical evidence and support for the effectiveness of metaverse platforms as a means of L2 speaking instruction.

Affective factors play a crucial role in the language learning process (Gardner & MacIntyre, 1993; Horwitz et al., 1986; Sun, 2019; Young, 1991). These factors significantly influence learners’ engagement, persistence, and success in acquiring a foreign language (Horwitz et al., 1986). Understanding the impact of affective factors on language learning outcomes is essential for developing effective teaching methods and learning strategies that cater to the diverse needs of language learners.

Research on the relationship between language learning and affective variables often focuses on factors such as interest, confidence, motivation, and anxiety (e.g., Ainley et al., 2002; Bandura, 1997; Gardner, 2001; Hortwiz, 2001; MacIntyre & Gardner, 1994). Interest in L2 learning is crucial for maintaining learners’ engagement and promoting successful language acquisition. Studies have demonstrated that increased interest in language learning positively correlates with improved L2 performance (Ainley et al., 2002; Renninger & Hidi, 2011). Factors contributing to learners’ interest include the relevance of the learning content to their lives, the challenge level of tasks, and the use of engaging instructional methods (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). Learners genuinely interested in the target language and its culture are more likely to actively engage in the learning process and consistently improve their language skills. Interest drives learners to explore new learning opportunities, seek authentic language input, and persist in challenging tasks. Additionally, confidence, or self-efficacy, is another key affective factor in L2 learning. According to Bandura (1997), self-efficacy plays a crucial role in shaping learners’ persistence, effort, and achievement, as individuals with higher self-efficacy are more likely to participate in speaking activities, take risks in their language use, and overcome setbacks during the learning process. Numerous studies have demonstrated that increased confidence in language learning leads to enhanced oral communication skills and overall language performance (Mills, 2014; Mills et al., 2007). These findings underscore the significance of building learners’ confidence in promoting successful L2 learning.

Furthermore, motivation is a driving force determining the amount of effort and persistence learners invest in language learning and it is critical for success in L2 learning (Dörnyei, 1998). Highly motivated learners are more likely to set challenging goals, dedicate time to practicing their language skills, and remain committed to achieving language proficiency. Research has consistently shown that motivation positively impacts language learning outcomes (Gardner, 2001). In a study by Dörnyei and Csizér (1998), they found that motivated learners tended to use more effective language learning strategies, which contributed to their success in L2 learning. This research highlights the importance of fostering motivation in L2 learners to enhance their language learning outcomes. Several factors can influence learners’ motivation, including the classroom environment, learners’ beliefs about language learning, and the perceived value of the target language (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011). Teachers can enhance motivation by adopting student-centered approaches, fostering a sense of autonomy, and promoting a positive classroom atmosphere (Alrabai, 2015).

Speaking anxiety, another important aspect of the affective domain, is a common challenge faced by language learners and can hinder their ability to effectively communicate in the target language. High levels of speaking anxiety can lead to avoidance of speaking activities, reluctance to participate in class discussions, and overall diminished speaking performance (Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre & Gardner, 1994). Researchers have investigated the impact of speaking anxiety on language learning performance and found that high levels of speaking anxiety negatively affect learners’ speaking proficiency, as anxious learners may avoid speaking activities or struggle to effectively express themselves in the target language (Horwitz et al., 1986; Phillips, 1992; Scovel, 1978). However, studies have also shown that interventions aimed at reducing speaking anxiety, such as providing a supportive learning environment, offering constructive feedback, and promoting learner autonomy, can lead to improvements in speaking performance and overall language proficiency (MacIntyre, 1995; Papi, 2010; Phillips, 1992; Woodrow, 2006).

Overall, affective factors play a vital role in determining the success of language learning experiences. By understanding the impact of factors such as interest, confidence, motivation, and speaking anxiety on language learning outcomes, educators can develop more effective teaching methods and learning strategies that cater to the unique needs of language learners.

Nonetheless, the empirical research specifically examining the effects of engaging in metaverse platforms for speaking practice on learners’ affective factors remains limited, as this innovative approach has only recently emerged in the literature. As previously mentioned, the significance of this study is underscored by the current scarcity of empirical research investigating the efficacy of metaverse platforms for enhancing L2 speaking proficiency and their impact on learners’ affective factors among EFL learners, as well as providing empirical evidence of their effectiveness. This study aims to address this research gap by conducting an in-depth investigation into the use of shadowing activities on the metaverse platform Gather, ultimately yielding empirical evidence and support for the effectiveness of metaverse platforms as a means of L2 speaking instruction. The current study is guided by the following research questions:

1. Do shadowing activities on metaverse platform Gather have a positive effect on improving EFL learners’ speaking proficiency?

2. Do shadowing activities on metaverse platform Gather have a positive effect on improving EFL learners’ affective aspects?

This study was conducted in compulsory college-level EFL courses in Korea. The courses meet twice a week for 100 minutes each, and the primary goal is to develop students’ English communication skills. A total of 49 students participated in this study and were grouped into experimental group 1 (n = 24, 11 males, 13 females), and experimental group 2 (n = 25, 13 males, 12 females). They were aged between 19-20 years old. Based on the results of an English proficiency test conducted in the first week of the study using the Oxford Placement Test, students were classified as intermediate-level learners with a score range of 51 to 59. Participants in experimental group 1 engaged in shadowing speaking activities using TED Talks videos on Gather, while participants in experimental group 2 engaged in shadowing speaking activities using TED Talks videos in a traditional classroom setting. According to the students’ background survey conducted in the first week of the study, all students had no experience living or studying in an English-speaking country. Only four students (8 % of the total) had prior shadowing activity experience, which they had learned individually during their free time to improve their English proficiency, rather than in a classroom setting.

In the first week of the semester, pre-oral tasks and questionnaires on affective attitudes, such as interest, motivation, confidence, and speaking anxiety, were administered to both the experimental and control groups in the classroom. Both groups followed the same textbook, 21st century reading: Creative thinking and reading with TED Talks 2 (Blass et al., 2016), and attended weekly 100-minute lectures in the classroom. The instruction involved studying relevant vocabulary and expressions related to the topics covered in each chapter, and reading materials related to the TED Talks videos. However, the speaking activities differed between the two groups. The experimental group practiced speaking through shadowing activities using TED Talks on the Gather platform online, while the control group engaged in the same shadowing activities but in a traditional face-to-face classroom setting.

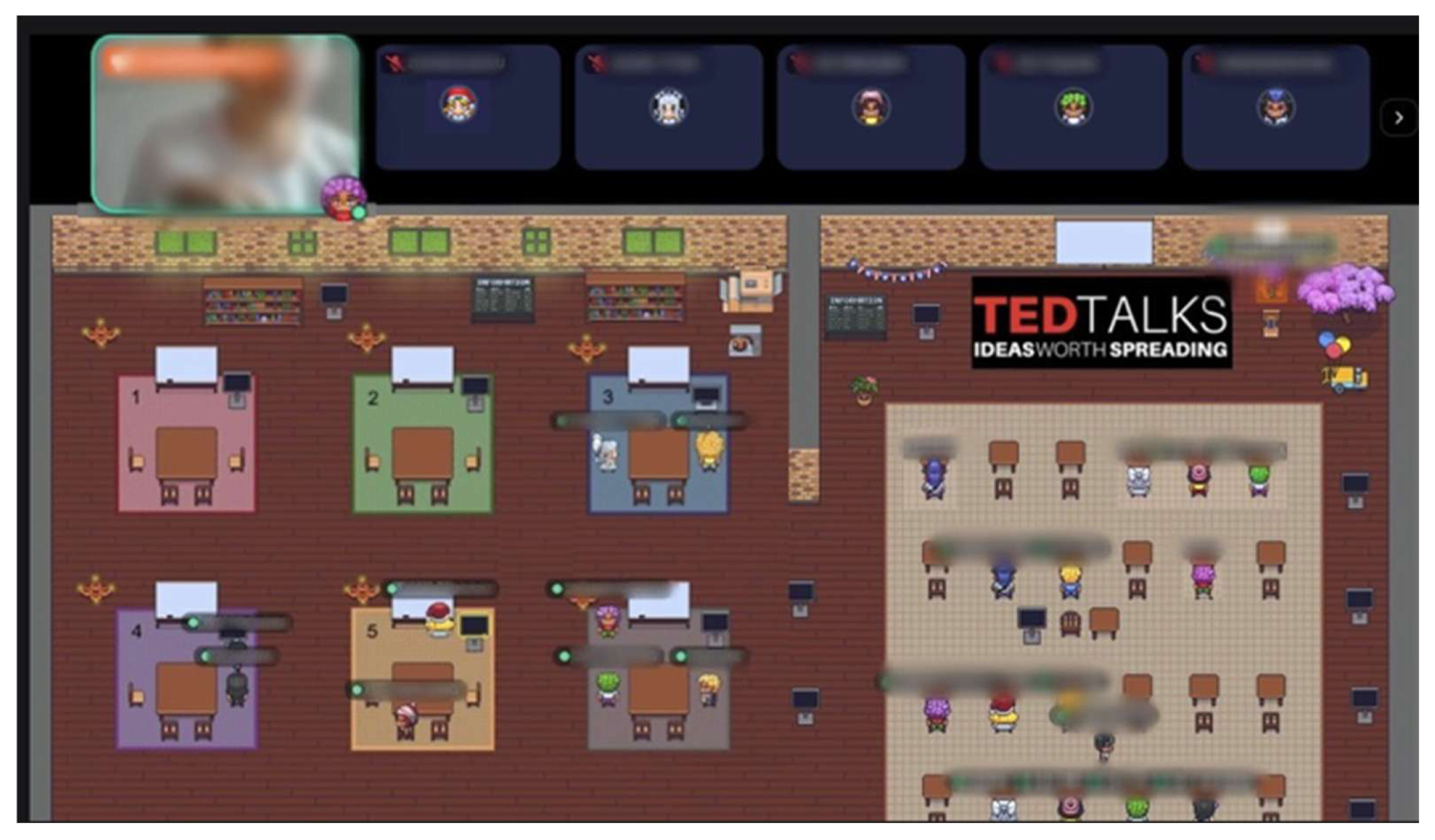

For the weekly shadowing activity for speaking practice, participants in experimental group 1 met online for 100 minutes in a virtual classroom on Gather. Students participated in the online sessions from their individual locations, allowing them to engage in the activities remotely and at their convenience. The researcher set up a virtual classroom on Gather, where TED Talks videos for each week were linked in TV screen objects in the virtual classroom. The participants were provided with scripts of the TED Talks videos to aid in their understanding of the content and clarification of the words and expressions used in the videos along with the lesson. In the first step of the shadowing activity, students watched selected TED Talks for each chapter, followed by shadowing activities. Students repeated sentence by sentence or line by line with the TED Talks videos at the same speed and volume. This activity was performed individually at their own pace. In this study, the shadowing method presented in Table 1 was adopted from Jin’s (2022) study, which modified Kim’s (2013) five-stage shadowing method. The five stages were as follows: Stage 1, shadowing without subtitles and without making sound (1-2 times); Stage 2, shadowing without subtitles but with speaking out loud (1-2 times); Stage 3, shadowing with subtitles and with speaking out loud; Stage 4, shadowing without subtitles but with speaking loud; Stage 5, repeating shadowing until the lines of each scene is perfectly shadowed (as many times as possible). Students were encouraged to repeat the shadowing activity until they felt they could proficiently follow the English lines, including pronunciation and intonation, at a native speaker’s pace within the given time, except for Stages 1 and 2.

After individual shadowing activities, participants entered a group room set up for group work on the Gather course platform. In groups of 2 or 3, participants took turns presenting their TED Talks shadowing and received feedback from peers, followed by a Q&A session. Next, as a whole class, several students were selected to give a speech as if they were a TED Talks presenter. The stage was set up in the Gather platform to resemble a TED Talks stage. The selected students virtually walked their avatars towards the stage and delivered their speeches in front of their peers, who played the role of the audience. After the presentation, they had a Q&A session as in a real TED Talks. The instructor ensured that all participants had this opportunity to present throughout the course. Participants’ speaking performance and presentation on the stage received corrective and supportive feedback from the instructor.

During one semester, a total of 10 weeks of shadowing activities were conducted, excluding the course orientation (week 1), midterm week (week 7, 8), evaluation (week 14), final exam (week 15). Each week, the students met online on Gather and watched TED Talks videos provided by the instructor, and learned various topics and contents through them, enabling them to engage in shadowing activities. The following Table 2 presents the list of the TED Talks used for shadowing activities in this study, along with their respective topics, arranged by class session.

The following Figure 1 illustrates one of the shadowing activities for English speaking practice conducted in this study. As shown on the Figure 1, the left side of the Gather classroom platform is dedicated to a space for group work, while the right side is a conference room where presentations for whole classroom can be given. A podium is placed at the front row to give students a sense of reality and the opportunity to physically step up and give their presentation, just as they would in real life. Throughout the semester, each of participants had the opportunity to present as a TED Talks presenter in front of the classroom after completing individual and group shadowing exercises.

Experimental group 2 participated in shadowing activities using TED Talks following the same procedure as experimental group 1, but in a traditional face-to-face classroom. They also met once a week for 100 minutes, just like experimental group 1, for shadowing activities. The shadowing activities followed the same steps as experimental group 1, with students watching TED Talks for each chapter and using scripts to aid in their understanding. The shadowing activity was done individually, following the five-stage shadowing method, and then presented in groups of 2 or 3, followed by a Q&A session. Same as experimental group 1, several students were selected to give a speech as if they were a TED Talks presenter in front of the class. The presentation was followed by a Q&A session and feedback from the instructor to improve their speaking performance.

Both groups of participants completed a pre-speaking task during the first week of the semester and a post-speaking task one week before the final week to determine whether there was an improvement in their speaking proficiency. The speaking task adopted for this study was based on the TOEIC speaking test and asked students questions related to their daily lives (e.g., ‘How long do you use the Internet every day?’, ‘What are your favorite activities to do while on vacation?’, etc.) The English speaking evaluations of the participants were recorded and evaluated using Brown’s (2001) speaking proficiency scoring scale, which assessed grammar, vocabulary, comprehension, fluency, pronunciation, and task on a 5-point scale with a total score of 6-30. The speaking evaluations of the participants were scored by two university-level English teachers in Korea, one being a native speaker of American English and the other a Korean teacher. Prior to scoring, both teachers received orientation on the evaluation method to ensure consistency in their criteria. The inter-rater reliability test showed high reliability for experimental groups 1 and 2, with pre- and post-evaluation results of .88 and .89, and .91 and .86, respectively.

In this study, pre- and post-questionnaire were conducted to examine any changes in affective attitudes of the participants towards language learning, including motivation, confidence, interest, and speaking anxiety. The survey questionnaire used in this study consisted of 16 items, with 4 items for each of the 4 subcategories, as seen in Table 3. The same survey was used for both pre- and post-surveys, and the survey was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The survey questions used in this study were tailored to fit the research goals and were derived from Jin’s (2022) study (interest, motivation, and confidence), as well as the Foreign Language Speaking Anxiety Scale (FLSAS) developed by Öztürk and Gürbüz (2014). In this study, the affective attitude survey instrument was evaluated for reliability, and the results showed high reliability. The pre-survey reliabilities were .77 for interest, .85 for confidence, .78 for motivation, and .77 for speaking anxiety, while post-survey reliabilities were .71 for interest, .74 for confidence, .74 for motivation, and .82 for speaking anxiety. These findings confirm the reliability of the survey instrument and support its use in this study. The survey questionnaire is available in Appendix for further information.

To analyze the data collected in this study, the SPSS 24.0 statistical program was used. The first research question focused on the impact of shadowing activities using TED Talks on Gather on learners’ speaking proficiency. To answer this question, pre- and post-speaking task results for both groups were analyzed using independent sample ttests and paired sample t-tests. Additionally, an independent t-test was used to compare the speaking task results for the six categories of speaking proficiency to provide a detailed analysis of development between the two groups. The second research question examined the effect of shadowing activities using TED Talks on Gather on affective attitudes, including interest, confidence, motivation, and speaking anxiety. To answer this question, pre- and post-affective attitude questionnaire results for both groups were analyzed using paired sample t-tests. The results of the survey related to speaking anxiety were analyzed by reversing the item scores to ensure that a high score indicated a positive outcome.

Prior to conducting the study, it was necessary to ensure that the English speaking proficiency levels of both experimental groups were comparable. Therefore, an independent t-test was conducted on the pretest results of the two groups for speaking abilities, which were administered at the beginning of the semester. The mean pretest score for experimental group 1 was 11.13 with a standard deviation of 1.54, while the mean pretest score for experimental group 2 was 11.76 with a standard deviation of 2.57. The results showed no statistically significant differences in the pretest scores between the two groups (t = -1.04, p = .30). This indicates that the English speaking proficiency levels of the two groups were equivalent before the study.

To address the first research question, this study examined whether there were any changes in the level of oral proficiency after participating in the study for both groups. The statistical comparison of pre- and post-test results for oral proficiency development is presented in Table 4, using paired samples t-tests to examine the effect of the intervention on participants’ speaking proficiency scores. The mean post-test score for experimental group 1 was 14.96, with a standard deviation of 2.66, which was significantly higher than the pretest mean score of 11.13 with a standard deviation of 1.54. This indicates an improvement of 3.83 points, and the difference between the two scores was statistically significant (t = -9.42, p < .001). Similar results were observed for experimental group 2, with a pretest mean score of 11.76 and standard deviation of 2.57, and a post-test mean score of 13.36 with a standard deviation of 1.93, showing a difference of 1.60. A statistically significant difference was found between the two evaluations (t = -3.70, p < .01). These findings provide evidence that the English speaking proficiency of all experimental group participants who engaged in TED Talks shadowing activities for one semester significantly improved, thus demonstrating the effectiveness of this method.

An independent t-test was further employed to compare the mean differences (post-test minus pre-test scores) between the two experimental groups in terms of speaking proficiency development. The results presented in Table 5 revealed that experimental group 1 had a significantly higher mean gain score on the speaking tests (Mean difference = 3.83, SD = 1.99) compared to experimental group 2 (Mean difference = 1.60, SD = 2.16). This significant difference in the mean gain scores of the two groups (t = 3.76, p < .001) suggests that the TED Talks shadowing activity group on the Gather platform was more effective in improving the participants’ speaking proficiency than the traditional classroom group. Therefore, these findings indicate that the use of the Gather metaverse platform was more advantageous than traditional classroom settings in enhancing the speaking proficiency of the participants.

To provide a more detailed analysis, this study investigated whether there were significant differences in the improvement of each component of speaking proficiency between the two experimental groups. The study focused on six categories, namely grammar, vocabulary, comprehension, fluency, pronunciation, and task. Table 6 shows the outcomes of an independent t-test on the mean differences for each category of speaking proficiency development for both groups. The statistical analysis indicated that the two groups exhibited significant differences in the areas of vocabulary (t = 2.62, p < .05), fluency (t = 2.36, p < .05), and pronunciation (t = 5.07, p < .001). However, no significant differences were found between the groups in the category of grammar (t = .573, p = .569), comprehension (t = -.71, p = .481), and task (t = -.225, p = .823). These findings suggest that shadowing activities on the Gather platform can be an effective method for enhancing specific areas of speaking proficiency development, such as fluency, pronunciation, and vocabulary. This further supports the potential of Gather platform as a viable alternative to traditional classroom settings for English speaking practice.

To address the second research question, this study examined whether there were changes in the levels of interest, confidence, motivation and speaking anxiety among learners in both groups after the intervention. The following Table 6 presents the results of a comparison of pre- and post-test results for the improvement of affective attitudes for each group in the study. As illustrated in Table 7, each of the affective factors, including interest (t = -4.70, p < .001), confidence (t = -4.98, p < .001), motivation (t = -2.93, p < .01), and speaking anxiety (t = -6.09, p < .001), demonstrated a significant enhancement for experimental group 1 following their participation in the study. In the case of experimental group 2, the factors of interest (t = -5.15, p < .001), confidence (t = -3.53, p < .01), and motivation (t = -2.85, p < .01) also exhibited a considerable increase after engaging in the study. However, no significant improvement was observed in the area of speaking anxiety for experimental group 2 after their involvement in the study (t = -.923, p = .365). It is essential to highlight that while experimental group 1 experienced a significant reduction in the level of speaking anxiety, there were no substantial changes detected in the level of speaking anxiety for experimental group 2. This finding indicated that participating in shadowing activities on Gather platform can have a positive impact on learners’ interest, confidence, and motivation towards English speaking proficiency. Moreover, the study suggests that shadowing activities on the Gather platform can be an effective intervention for reducing learners’ speaking anxiety. Considering the fact that no significant change exists in the shadowing activities in the conventional classroom setting, the findings imply that Gather can provide a more favorable environment for learners to improve their affective attitudes towards English speaking proficiency, especially in terms of reducing speaking anxiety.

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of shadowing activities on the Gather platform in improving English speaking proficiency and affective attitudes. Specifically, the study sought to examine the potential role of the Gather metaverse platform for enhancing speaking proficiency and affective factors in comparison to the traditional classroom. The results showed that both experimental groups significantly improved their English speaking proficiency after participating in TED Talks shadowing activities for one semester. This finding empirically supported that the shadowing activity for English speaking practice is an effective approach for developing EFL learners’ speaking proficiency. This is in line with previous studies of Kim (2013), Kim (2018), Lee et al. (2010), and Park (2013), which demonstrated the positive outcome of shadowing activities for EFL learners’ development of speaking proficiency.

Moreover, the results revealed that the Gather platform was more effective in enhancing the speaking proficiency of the participants compared to the traditional classroom environment that also engaged in the same shadowing activities. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that metaverse platform can be effective in improving language proficiency (Lee & Ahn, 2022; Lim, 2022). Additionally, the study showed that the Gather platform was more effective in enhancing specific areas of speaking proficiency development, such as fluency, pronunciation, and vocabulary. Based on the data collected, it is possible to speculate that the Gather platform may offer a more immersive and interactive learning experience for language learners, which could potentially lead to more effective and efficient language learning outcomes. There are several possible reasons for this. Firstly, the platform’s use of avatars and virtual environments may have created a more engaging and dynamic learning environment that motivated learners to participate more actively in the TED Talks videos and shadowing activities. Additionally, the flexibility of the Gather platform empowered learners to practice their English skills at their own pace and in their preferred settings, catering to their unique learning needs. This feature allowed learners to use online resources, such as dictionaries, to look up the definitions and pronunciations of unfamiliar words or phrases encountered during the TED Talks videos. This way, learners could address their areas of improvement more effectively, making their language learning experience more efficient and effective. Lastly, the Gather platform facilitated more effective feedback and peer interaction, as students could collaborate and communicate with each other in real-time using avatars. This feature may have contributed to an increase in speaking opportunities, as learners received immediate feedback on their performance and were able to practice speaking with their peers in a supportive environment. Additionally, the use of avatars can help learners hide moments of embarrassment or worry about receiving negative feedback from peers. However, further research is needed to confirm these assumptions. Overall, the results of the study suggest that the use of the Gather metaverse platform provided a more effective and engaging learning environment for improving English speaking proficiency among the participants, and it has the potential to be a viable alternative to traditional classroom settings for English speaking practice.

Furthermore, the results of the affective attitude assessment demonstrated that participating in shadowing activities on Gather platform can positively impact learners’ interest, confidence, motivation, and speaking anxiety towards English speaking proficiency. In particular, the experimental group that engaged in shadowing activities on Gather platform showed a significant decrease in their level of speaking anxiety, which is a crucial factor in improving learners’ overall speaking performance. The virtual environments and avatars used in Gather create a sense of presence and immersion that may enhance the learning experience, especially for learners who struggle with traditional classroom settings. This may be particularly beneficial in reducing learners’ speaking anxiety, as the platform provides a more comfortable and supportive environment for learners to practice their speaking skills. This is consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness of online learning environments in reducing stress and speaking anxiety among English language learners (Jeon, 2022; Namaziandost et al., 2022). The Gather platform has also been found to have the potential to reduce learners’ speaking anxiety and improve their speaking proficiency. Speaking anxiety is a common issue among language learners and can significantly hinder their ability to improve their speaking skills (Horwitz et al., 1986; Young, 1991). By reducing speaking anxiety, learners may feel more comfortable and confident when communicating in English, which can lead to more effective language learning and increased motivation to continue practicing their skills. The findings of this study suggest that shadowing activities on the Gather platform can be an effective intervention for reducing learners’ speaking anxiety and improving their overall speaking performance. This is particularly important in language learning, where anxiety can have a significant impact on learners’ motivation and willingness to communicate in a foreign language. By providing a supportive virtual environment that promotes interaction and feedback, the Gather platform can help learners overcome their anxiety and build confidence in their speaking abilities, leading to more successful language acquisition. The potential of Gather as a tool for English language learning is significant, and further research is needed to fully explore its capabilities and effectiveness in enhancing speaking proficiency and reducing speaking anxiety.

The study’s conclusion highlights the effectiveness of the Gather platform in improving English speaking proficiency and affective attitudes towards speaking English. The use of avatars and virtual environments in Gather provided a more engaging and immersive learning environment compared to traditional classroom settings and created a supportive environment that reduces speaking anxiety, leading to improved overall speaking performance and enhanced learning experiences for language learners. This study builds upon earlier findings that emphasize the potential of new technologies, such as metaverse platforms, for enhancing language learning and teaching practices (Lee & Ahn, 2022; Lim, 2022). The results of this study, along with existing research, suggest that Gather could be a promising alternative to traditional classroom settings for English speaking practice, particularly for learners struggling with speaking anxiety. Moving forward, future studies could further investigate the effectiveness of virtual environments in language learning and explore ways to optimize their use for language learning. This includes examining different instructional strategies, analyzing the impact of virtual environments on other language skills, and exploring the benefits of combining virtual environments with traditional teaching methods. By building on both this study and previous research, educators and researchers can continue to advance our understanding of how best to utilize virtual environments to enhance language learning outcomes.

The pedagogical implications of the study suggest that language instructors should consider incorporating Gather into their teaching methods for English speaking practice. The platform provides a more immersive and interactive learning environment that enhances learners’ speaking proficiency, reduces speaking anxiety, and enhances learners’ affective attitudes. Additionally, the platform’s flexibility allows learners to practice at their own pace and in their preferred settings, which can result in more targeted language practice. Furthermore, the interactive and engaging features of the platform can facilitate peer interaction, helping learners improve their speaking proficiency by practicing speaking with their peers in a supportive environment. Moreover, incorporating Gather as an assignment or out-of-class activity in offline classrooms could offer an innovative approach to language learning, making it more dynamic and engaging for learners. By integrating virtual environments into traditional teaching methods, instructors can create a complementary learning experience that combines the advantages of both online and offline learning contexts. This approach can also help learners struggling with speaking anxiety by providing a more supportive and low-pressure environment for speaking practice. Overall, incorporating Gather into language teaching practices can potentially revolutionize English speaking practice and provide learners with an effective alternative to traditional classroom settings.

However, this study has some limitations. The research was conducted in a specific context and with a relatively small sample size. Therefore, the generalizability of the results may be limited. Additionally, the study only focused on the effectiveness of the Gather platform for English speaking practice, and further research is needed to investigate its effectiveness for other language skills and in different contexts. Further research is required to confirm the generalizability of the findings and to explore the platform’s effectiveness for other language skills and in diverse settings.

TABLE 1

The Five Stages of a Shadowing Method for Speaking Proficiency

TABLE 2

The List of Selected TED Talks

| Topic | TED Talks videos | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Starting up | How to start a movement by Derek Sivers (TED, 2010d) |

| 2 | Fragile forests | Explores canopy world by Nalini Nadkarni (TED, 2009a) |

| 3 | Bright ideas | A warm embrace that saves lives by Jane Chen (TED, 2010a) |

| 4 | Game changers | Gaming can make a better world by Jane McGonigal (TED, 2010c) |

| 5 | Lesson in learning | The key to success? Grit by Angela Lee Duckworth (TED, 2020) |

| 6 | Food for life | Teach every child about food by Jamie Oliver (TED, 2010b) |

| 7 | Body signs | Your body language shapes who you are by Amy Cuddy (TED, 2012) |

| 8 | Energy builders | How I harnessed the wind by William Kamkwamba (TED, 2009b) |

| 9 | Changing perspectives | Deep sea diving…in a wheelchair by Sue Austin (TED, 2013) |

| 10 | Data detectives | The beauty of data visualization by David McCandless (TED, 2010e) |

TABLE 3

The Questionnaire Categories for Affective Attitudes

| Category | Sub-category | Survey item |

|---|---|---|

| Affective attitudes | Interest | 1, 5, 9, 13 |

| Confidence | 3, 7, 11, 15 | |

| Motivation | 4, 8, 12, 16 | |

| Speaking anxiety | 2, 6, 10, 14 |

TABLE 4

Comparison of Pre- and Post-Test Results for Oral Proficiency Development

| Group | Test | N | M | SD | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre | 24 | 11.13 | 1.54 | −9.42 | 23 | .000 |

| Post | 24 | 14.96 | 2.66 | ||||

| 2 | Pre | 25 | 11.76 | 2.57 | −3.70 | 24 | .001 |

| Post | 25 | 13.36 | 1.93 |

TABLE 5

Mean Differences (Post-Test Minus Pre-Test Scores) in Speaking Proficiency Between Groups

| Group | N | Mean differences | SD | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24 | 3.83 | 1.99 | 47 | 3.76 | .000 |

| 2 | 25 | 1.60 | 2.16 |

TABLE 6

Mean Differences (Post-Test Minus Pre-Test Scores) in Oral Proficiency Across Six Categories Between Groups

TABLE 7

Comparison of Pre- and Post-Test Results for Changes in Affective Attitudes

REFERENCES

Acceleration Studies Foundation (ASF). (2006). May 5-6; Metaverse roadmap: Pathways to the 3D web. https://www.metaverseroadmap.accelerating.org/.

Ainley, M., Hidi, S., & Berndorff, D. (2002). Interest, learning, and the psychological processes that mediate their relationship. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 545-561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.545.

Alrabai, F. (2015). The influence of teachers’ anxiety-reducing strategies on learners’ foreign language anxiety. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 9(2), 163-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2014.890203.

Amoli, F. A., & Ghanbari, F. (2013). The effect of conversational shadowing on enhancing Iranian EFL learners’ oral performance based on accuracy. Journal of Advances in English Language Teaching, 1(1), 12-23.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company.

Blass, L., Vargo, M., & Yeates, E. (2016). 21st century reading: Creative thinking and reading with TED Talks 2. National Geographic Learning,

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd ed). Pearson Education.

Choi, J. H. (2022). An analysis of metaverse studies in English education in Korea. Studies in English Education, 27(3), 353-380. https://doi.org/10.22275/SEE.27.3.06.

Chung, D. U. (2010). The effect of shadowing on English listening and speaking abilities of Korean middle school students. English Teaching, 65(3), 97-127. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.65.3.201009.97.

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31(3), 117-135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X.

Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2(3), 203-229. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216889800200303.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed). Pearson Education.

Gardner, R. C. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition. pp 1-19. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre, P. D. (1993). A student’s contributions to second language learning. Part II: Affective variables. Language Teaching, 26(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800000045.

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4.

Horwitz, E. K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 112-126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190501000071.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.2307/327317.

Jang, J. Y. (2021). A study on a Korean speaking class based on metaverse: Using Gather.town. Journal of Korean Language Education, 32(4), 279-301. https://doi.org/10.18209/iakle.2021.32.4.279.

Jeong, Y. S., Lim, T. H., & Ryu, J. H. (2021). The effects of spatial mobility on metaverse based online class on learning presence and interest development in higher education. The Journal of Educational Information and Media, 27(3), 1167-1188. https://doi.org/10.15833/KAFEIAM.27.3.1167.

Jeon, J. (2022). Exploring AI chatbot affordances in the EFL classroom: Young learners’ experiences and perspectives. Computer Assisted Language Learning, https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.2021241.

Jin, S. H. (2022). The effects of a shadowing activity using movies on Korean EFL college learners’ speaking skills and their affective attitudes. Journal of English Teaching through Movies and Media, 23(1), 27-41. https://doi.org/10.16875/stem.2022.23.1.27.

Kim, G. H. (2013). Effects of shadowing on English listening and speaking abilities of elementary school student (Unpublished master’s thesis) Gyeongin National University of Education, Incheon.

Kim, J. H. (2018). The effects of shadowing with English movies on Korean EFL college students’ listening and speaking achievement, and learning interest and attitudes (Unpublished master’s thesis). Chosun University: Gwangju.

Lee, B. R., & Choi, E. K. (2022). A study on beginner Korean speaking education using metaverse: Focusing on metaverse platform ZEP. Culture and Convergence, 44(10), 99-115. https://doi.org/10.33645/cnc.2022.10.44.10.99.

Lee, D. K., Kim, D. W., & Byeon, S. J. (2022). Analysis of the status and perception of elementary and secondary school students on the metaverse in education. Journal of Learner-Centered Curriculum and Instruction, 22(12), 443-458. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2022.22.12.443.

Lee, G. Y., & Kim, H. J. (2020). The effects of virtual reality based English learning on vocabulary achievements and affective domains of elementary students. Journal of Learner-Centered Curriculum and Instruction, 20(16), 1213-1235. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2020.20.16.1213.

Lee, N. E., Lee, H. J., & Jang, D. S. (2010). A study on the effect of shadowing for the improvement of middle school students’ oral communication. The Journal of Modern British & American Language & Literature, 28(4), 89-108.

Lee, S. M., & Ahn, T. Y. (2022). Middle school students’ interactional behaviors and perception of English speaking activities in metaverse. Secondary English Education, 15(3), 25-44. https://doi.org/10.20487/kasee.15.3.202208.25.

Lim, J. Y. (2022). Mediated effect of mentoring between functional elements of metaverse and learning motivation English debate learning. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society, 23(12), 318-330. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2022.23.12.318.

MacIntyre, P. D. (1995). How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply to Sparks and Ganschow. The Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 90-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05418.x.

MacIntyre, P., & Gardner, R. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Language Learning, 44(2), 283-305.

Mills, N. (2014). Self-efficacy in second language acquisition. In S Mercer & M Williams (Eds.), Multiple perspectives on the self in SLA. pp 6-22. Multilingual Matters.

Mills, N., Pajares, F., & Herron, C. (2007). Self-efficacy of college intermediate French students: Relation to achievement and motivation. Language Learning, 57(3), 417-442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00421.x.

Namaziandost, E., Razmi, M. H., Hernández, R. M., Ocaña-Fernández, Y., & Khabir, M. (2022). Synchronous CMC text chat versus synchronous CMC voice chat: Impacts on EFL learners’ oral proficiency and anxiety. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(4), 599-616. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1906362.

Öztürk, G., & Gürbüz, N. (2014). Speaking anxiety among Turkish EFL learners: The case at a state university. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 10(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.17263/JLLS.13933.

Papi, M. (2010). The L2 motivational self system, L2 anxiety, and motivated behavior: A structural equation modeling approach. System, 38(3), 467-479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2010.06.011.

Park, Y. J. (2013). The effects of the shadowing learning method on Korean university students’ English listening and speaking skills (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) Hoseo University, Chungnam.

Phillips, E. M. (1992). The effects of language anxiety on students’ oral test performance and attitudes. The Modern Language Journal, 76(1), 14-26. https://doi.org/10.2307/329894.

Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (2011). Revisiting the conceptualization, measurement, and generation of interest. Educational Psychologist, 46(3), 168-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.587723.

Ryu, G. Y. (2010). The effect of shadow reading on the improvement of Korean learners’ listening comprehension and their learning attitudes: By targeting learners for academic purposes (Unpublished master’s thesis) Ewha Womans University, Seoul.

Scovel, T. (1978). The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the anxiety research. Language Learning, 28(1), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1978.tb00309.x.

Sun, Y. (2019). An analysis on the factors affecting second language acquisition and its implications for teaching and learning. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 10(5), 1018-1022. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1005.14.

TED. (2009a). March 5; Explores canopy world Nalini Nadkarni [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rN7VcY1f-1Q&t=11s.

TED. (2009b). September 24; How I harnessed the wind William Kamkwamba [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=crjU5hu2fag.

TED. (2010a). January 29; A warm embrace that saves lives Jane Chen [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IwidCkCmWg4.

TED. (2010b). February 13; Teach every child about food Jamie Oliver [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=go_QOzc79Uc&t=179s.

TED. (2010c). March 18; Gaming can make a better world Jane McGonigal [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dE1DuBesGYM.

TED. (2010d). April 2; How to start a movement Derek Sivers [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V74AxCqOTvg.

TED. (2010e). August 23; The beauty of data visualization David McCandless [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLqjQ55tz-U.

TED. (2012). October 2; Your body language shapes who you are Amy Cuddy [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ks-_Mh1QhMc&t=168s.

TED. (2013). January 9; Deep sea diving…in a wheelchair Sue Austin [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PCWIGN3181U.

TED. (2020). March 21; The key to success? Grit Angela Lee Duckworth [Video]. YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_XOWsgMd5fA.

Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC Journal, 37, 308-328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206071315.

- TOOLS

- FOR CONTRIBUTORS

-

- For Authors

- Instructions for authors

- Regulations for submission

- Author’s checklist

- Copyright transfer agreement and Declaration of ethical conduct in research

- Conflict of Interest Disclosure Form

- Disclosure Form for People with Personal Connections

- E-submission

- For Reviewers

- Instructions for reviewers

- How to become a reviewer

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print