Critical Literacy and Semiotic Juxtaposition: The Possibilities of Multimodal Pedagogy in Korea

Article information

Abstract

The various explanations and definitions of critical literacy share key characteristics with Peirce’s semiotic theory regarding the ideological nature of texts, readers, and interpretive practices. This article locates critical literacy in the semiotic juxtaposition of signs, and uses Pierce’s (Freadman, 2004) classification of signs as icons, indexes, or symbols, as a semiotic framework to analyze two multimodal literacy events as critical practice. Teachers and researchers can use this semiotic framework to identify, qualify, and design multimodal texts and interpretive events that contribute to critical literacy practices. Through an analysis of critical literacy, semiotic theory, and multimodal project examples from two American middle school classrooms, this paper seeks to illustrate how such pedagogies may enhance the teaching practices of language teachers, including Korean EFL teachers, in ways that will increase students’ critical thinking skills and better understand how they are being ideologically positioned by representational meanings in all forms of textuality. In addition, it will be shown how such pedagogies may enhance students’ social agency as well as benefit their society. The purpose of this paper is not only to discuss these issues, but also to illustrate why the theories and pedagogies discussed should be included in Korean English teacher education.

I. INTRODUCTION

The Critical literacy is generally believed to have begun with Freire’s (1970) seminal work Pedagogy of the Oppressed which theorized a new form of literacy that rejected autonomous forms of literacy, which Freire called banking, into a form of literacy that viewed textuality as ideological. Freire’s theorization was derived from Marxist theory, the neo-Marxism of the Frankfurt School, and what has become known as poststructuralism (Luke, 2012). Freire’s pedagogy for enacting critical literacy included the reading of a text, be it written or visual, situating it into differing socially relevant contexts, discussing, and debating what students have found, and publishing the results of their inquiry. Since then, critical literacy has been further developed by a wide range of scholars from differing academic disciplines and has become a political movement in education known as critical pedagogy that is specifically invested in issues of social justice, social agency, and the furthering of democratic principles (Apple, 2004; Giroux, 1997; Luke, 2012, Pennycook, 2001). In addition, it has also helped to inform the educational movements of multiliteracies and multimodality in ways that often elide these three terminologies (Jewett, 2007; Kress, 2000). As such, critical literacy views textuality as including the written word, film, images, media representations, and all information communication technologies (ICT). As such, the idea of critical literacy has become commonplace in reading and language education and has had several extensive articulations over the past two decades (Beck, 2005; Behrman, 2006; Cervetti, Pardales, & Damico, 2001, Fairclough, 1992; Fehring & Green, 2001; Gee, 1992; Iyer, 2007; Lankshear & McClaren, 1993; Morgan, 1997; Shor, 1999; Stevens & Bean, 2007). Critical literacy has also seen increasing use in English as a foreign language (EFL) pedagogy as well (Canagarajah, 1999; Luke, 2012; Morgan & Ramanathan, 2005; Norton & Toohey, 2004; Pederson, 2019; Pennycook, 2001). These authors describe interpretive activity with print and/or multimedia texts in similar ways to represent meaning making as a type of thinking or knowing that is referred to as critical. The characteristics of the critical literacy events they define are at times comparable, and at other times complementary aspects of a broader interpretive practice that can be named as critical literacy. In defining a critical literacy, the focus is at times on the nature of the text, on the cultural background of the reader and their interpretive response, on the social context and purpose of the interpretive event, or on all three as they constitute a literacy practice that has the characteristics of being criticical.

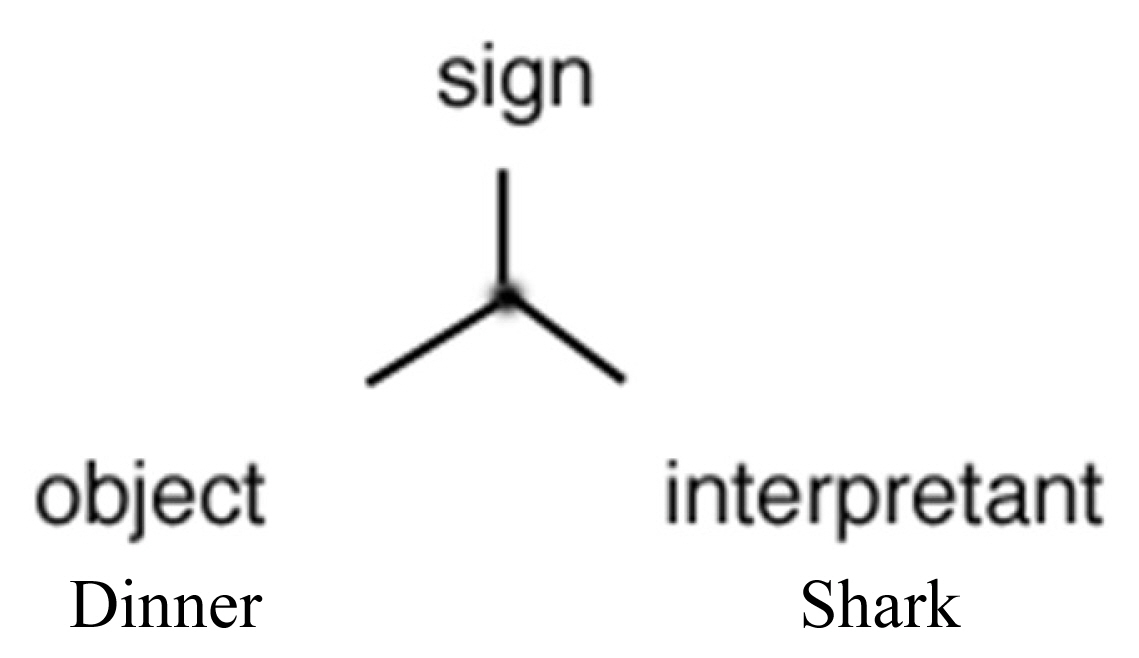

Semiotics is an academic discipline that seeks to define and better understand how meaning is encoded into language. Ferdinand Saussure and Charles Peirce were the pioneering scholars of semiotics in the 19th century (Freadman, 2004; Hall, 1997). In simple terms, semiotics focuses on signs, comprised of the signifier (object or word) and the signified (meaning as constructed in the individual mind) to determine the function and meaning of language. However, it was Pierce that theorized how a third aspect of the sign, the interpretant, functioned as the mediating factor of a sign as the interpretant serves as an individual representation of meaning within the human landscape of language and meaning. As such, meaning is always in flux and an interpretant is always a representation of another interpretant, or representation (Freadman, 2004). It is important to understand that there are dyadic and triadic interpretations of signs in semiotics; where the dyadic interpretation focuses on one specific meaning of a sign and the triadic interpretation is open to the multiplicity of meanings of interpretants that are in constant flux through social interactions. In addition, it is also crucial to understand that representations of meaning may focus on the possible meanings embedded in a specific sign within a text or may analyze the milieu of representations that focus on an issue or meaning in a society, such as how Black men are represented in media. Both approaches to representation and meaning allow one to better understand the ideological production and repercussions of such representations and how to counter them (Hall, 1997). In both ways, semiotic analysis dovetails with the basic goals of critical literacy.

Critical literacy began as a pedagogical initiative designed to not only foster the common literacy of students, but to also to develop students critical thinking skills through the situating and questioning of bodies of knowledge and all texts, including visual media, to improve student’s social agency for the purposes of social justice and the strengthening of democratic principles. The resulting conscientization of a student’s worldview and consciousness is viewed as the key to unlocking the potential to improve an individual’s and group’s social positioning (Freire, 1970; Luke, 2012). As such, critical literacy is not limited to traditional concepts of textuality, i.e., the written word, but includes media representations and ICT as well. Thus, for an individual to better understand her social positioning in society, she needs to decode the representational meanings that daily bombard her consciousness more accurately. For these reasons, semiotic theory is of great use to critical literacy practices as semiotics is fundamentally about the encoding, decoding, and interpreting the representational meanings of signs (Freadman, 2004; Hawkes, 1997). This pedagogical practice is both useful and important to EFL as its pedagogical practices increasingly utilize multimodal forms of textuality (Gray & Lee, 2019; Kress, 2002; Royce, 2002; Van Leeuwen, 2015). Indeed, EFL teachers are increasingly using film, the internet, and educational software in their teaching practices (Kaiser, 2011; Park, 2020). As the multimodal examples of critical literacy used in this paper are student made video representations of an issue or ideation derived from specific texts, it is important to note that such practices, as well as video story telling (VST), are increasingly used in EFL classrooms as well (Akdeniz, 2017; Chen, 2018; Hung, Keppell, & Jong, 2004; Naqvi, 2016; Nikitina, 2009; Pederson, 2018: Puspa, 2016). In addition, as EFL is dominated by the methodologies of the Grammar Translation Method (GTM) and the Audiolingual Method (ALM) (Shin, 2010), which present a specific dyadic meaning to words in a given context, triadic semiotic interpretations of language would both foster the language learning of our students as well as give them a greater insight into the target culture (Chen, 2018; Hung & Huang, 2015; Naqvi, 2016). The purpose of this paper is to theoretically examine how and why semiotic theory may benefit critical literacy practices in EFL contexts. Using two American middle-school critical literacy student video projects as examples for the pedagogical processes of critical literacy, and how semiotic theory adds to this process, this paper hopes to demonstrate how this approach is applicable to both K-12 classroom practices as well as English teacher education in Korea.

II. CRITICAL LITERACY AND SEMIOSIS

Semiotic theory posits that signs always have meaning within an ideological context of other signs, while critical literacy practices seek readers who can identify the framing of social contexts and give voice to their silent underlying values. Therefore, semiotic theory applied to critical literacy can escape a deterministic reproduction of the social identities and meanings attributed to the ideological text masquerading as a corresponding description of reality. Critical literacy is a kind of pedagogy with specific aims about making visible to students the inherently social nature of language and how texts are positioning them ideologically (Mission & Morgan, 2006). Critical literacy requires an explicit examination of the connections between a sign and its ideological context that values specific objects, actions, and social relationships. Essentially, critical literacy and semiotics recognize how representations of meanings across all forms of textuality socialize people into specific ideologies and constructed desires. (Knickerbocker & Rycik, 2006). In doing so, critical literacy can interrupt the social and multimodal processes of socialization that position the young into specific ideologies and identities in ways that allow them to choose what benefits them and their societies. Thus, critical literacy brings awareness to one’s assumptions, beliefs, and attitudes. This burgeoning awareness increases the insight into how our identities shape our meanings for signs and broadens the focus of critical literacy beyond how texts are ideological to how one’s own identity is a collocation of ideological signs (Shor, 1999).

The critical literacy utilized in this paper is not difficult understand or use as it begins with introducing students to the nature of critical literacy and semiotics through examples and does not use any theoretical terminology. This may be done by the teacher showing the students a specific text and questioning them as to possible meanings, following this with a discussion of the nature of these differing interpretations of meaning. Similarly, the teacher may show a text, or texts, and point out how many ways the meaning changes according to its interpretation. These textual investigations and explanations are followed by situating the meanings in multiple contexts, or engaging in inquiry, which leads to group discussions that transform the knowledge and meanings within the textual representations. This interpretation/response of the reader of any form of textuality is often considered to be the first step towards criticality (Groenke, 2008). This means that representational meanings are never fixed, that all representations are ideological in nature, and that every individual derives ideological meanings from textuality. Therefore, the primary purpose of critical literacy is for students to become aware of how representations and meaning position them ideologically and to understand if this positioning benefits them or others. In order to achieve such outcomes, teachers need to create a supportive space withing the classroom that allows for student experiences to enter into group discussions so that students may come to better understand how textuality attempts to socially and ideologically position them in specific ways: ways that are not always to their benefit (Beck, 2005).

What is common across definitions of critical literacy is the need to first understand meaning as ideological in all three components of interpretation (text-reader-response), then to examine, even debate, our relative and differential support for particular values and beliefs, then to finally examine how these values and beliefs permeate the words, images, gestures, and actions we signify in our symbolic interactions with others. In dealing with the socio-cultural orientations of language, and through this with the political nature of language, critical literacy moves beyond the textual, to questions of ideology (Iyer, 2007). This literacy practice, which Street (1995) calls “autonomous,” is problematic because it separates oneself from the world such that one is always dependent upon authority to name and define experience. This autonomous form of literacy practice is also indicative of traditional EFL practices, such as the GTM and the ALM, that not only recognize one correct answer, but also conform to the meritocracy of high stakes testing and social reproduction (Shin, 2010).

Critical literacy practices attempt to bring interpreters into the negotiation of subjective experiences of the social world in order to arrive at intersubjective values and beliefs that result in explicit and public articulations of a more socially just distribution of power. This leads learners to a greater sense of control or agency over how one’s possible identities are defined, how one’s relationships might develop, and how one’s purposes in life can be mutually achieved with others’ desires.

As a theory, critical literacy espouses that education can foster social justice by allowing students to recognize how language is affected by and affects social relations. Among the aims of critical literacy are to have students examine the power relationships inherent in language use, recognize that language is not neutral, and confront their own values in the production and reception of language.

(Behrman, 2006, p. 490)

Therefore, to engage in critical literacy practice, students and teachers need to symbolically engage with texts and each other in ways that continually invite each other to uncover and explicate the underlying beliefs and values that arise through our symbolic interaction and move our joint social activity forward toward some pragmatic goal. This pedagogical process of making ideology visible in order to negotiate it with others enables us to exercise a level of agency and control in the construction of our own identity and the identities of those with whom we interact. As such, this form of pedagogy facilitates the growth of an awareness of how textuality is used for the purposes of the producer, which in turn fosters considerations for taking social action for one’s own social agency (Dozier, Johnston, & Rogers, 2006). Just what this uncovering of underlying ideological assumptions, beliefs, and values might look like, how it impacts our understanding of the ways in which we use language, and how students might direct their awareness towards social action, is of keen interest to literacy teachers and researchers who hope to construct critical literacy practices. Here is where Pierce’s (Freadman, 2004) description of signs and semiosis may illuminate the critical practices we seek, and provide metaphors that can help students, teachers, and researchers make critical thought more explicit.

To better understand the nature of semiotics and representation as foundational aspects of critical literacy, it is necessary to briefly discuss how representation is generally viewed in the social sciences. Hall’s (1997) seminal work Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices, gives a historical view of theories of language and meaning that include Saussure’s (2012) semiotics, through discourse theory, to the current use of representation in the social sciences. While Hall (1997) does cover basic semiotic theory, he does not dig deeply into the nature of Pierce’s (Freadman, 2004) theory of the interpretant, which theorizes how representation functions in the human mind and social practices but leads the reader to post-structural theories of discourse to lead to his final view of how representations function socially (Hall, 1997). This difference between these two ideations of representation is necessary to understand how and why Hall’s view of discursive representation is the most used theory of representation in the social sciences. Indeed, it is common for representational theory to be referred to as theories of representation as several iterations exist in the social sciences. Although they are, in effect, doing the same theoretical analyses, they differ in a profound way. Semiotics deals with the representations of signs in a micro way as it explicates the workings of individual signs while discursive views of representation examine macro, or discursive, uses of representations as they function in societies.

Through a discursive focus, analyses may illustrate how and why there are dominant and alternative representations existing in media, what discourses they benefit, and how and why they may be changing. A good example of this is how gender inequality is analyzed in terms of women being represented in various films as brainless sexual objects, or at least in supportive positions of men (Kitsinger, 2010), or even how successful female entrepreneurs are often also similarly stereotyped despite their success, and signaling positive change is occurring (Nadine, Smith, & Jones, 2020). Regardless of this differing approach to representation, both means of analysis are based on semiotics and deal with the ideological nature of signs. Finally, critical approaches to EFL commonly use Hall’s (1997) macro form of representation for analyses of wide-ranging topics (Luke, 2012; Morgan & Ramanathan, 2005; Norton & Toohey, 2004; Royce, 2002; Shah & Elyas, 2019). In terms of the pedagogy of representational meanings, semiotic theory looks at individual signs at the OBJECT level, whereas discursive theories of representation examine representations at the societal level. Examples of the use of such representational theory in second language include Kubota’s (2001) study of how American education was represented in Japanese educational discourse, Nguyen’s (2017) study on the representations of native English-speaking teachers, and Davis and Skilton-Sylvester’s (2004) inquiry into the lack of gender education in TESOL practices. These insights lead to an understanding that the semiotics of signs are not only a part of discourse, but also serve to structure and maintain the ideologies of the various discourses that exist internationally and within a society.

Finally, different discourses bring different interpretants to texts. Discourses might be understood as collections of triadic signs that define the possible meanings of signs in multimodal and linguistic experiences by bringing specific interpretants to the signs of a text. A discourse that is dominant will often bring interpretants to a sign that are largely implicit and hidden, thus the discourse seems to carry the meaning of a sign. A linguistic or multimodal text can be deconstructed by bringing it in relationship to different multiple discourses in which meaning may be contrasted and contested by contextualizing a sign with different interpretants. Discourses are collections of triadic signs that serve to identity their power and purposes by organizing interpretants to frame a particular definition or meaning for a sign in any linguistic or multimedia text.

1. The Dyadic Sign

As we use symbols and language, and enact gestures and actions, we offer many signs for interpretation to those with whom we socially interact. As Vygotsky (1981) argued, these signs in external social interaction are internalized as ways of thinking that constitute consciousness:

The very mechanism underlying higher mental functions is a copy from social interaction; all higher mental functions are internalized social relationships. . . Even when we turn to mental [internal] processes, their nature remains quasi-social. In their own private sphere, human beings retain the functions of social interaction. (p. 164)

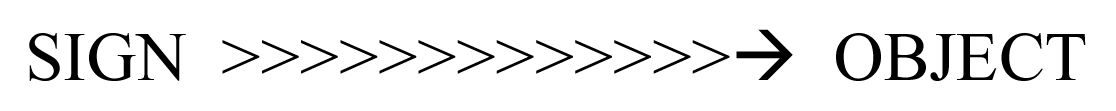

In an everyday sense, the predominate way of thinking about meaning is illustrated in the diagram below:

The OBJECT is the meaning that one has for a sign. This way of thinking–that things have a specific name we can share and a definition upon which we can agree–arises in our early social interactions as a pragmatic consequence of communication with others in order to live in the world. In other words, the object is the mental representation of meaning for the words, physical objects, mannerisms, and concepts we are exposed to in our daily lives. We commonly take for granted the OBJECT meaning of thousands of signs that we have at some earlier time negotiated the meaning through symbolic interaction (Blumer, 1969). The physical objects in our house, i.e., forks, doors, ceilings, water, computer, furnace, etc., are signs that typically function with this dyadic meaning. The emotional signs in our home might be more spontaneous, evolving, or changeable; however, over time in social interaction, a particular word or gesture from a partner or child, or even oneself, can be fixed to a particular meaning. This reification of language is also a common way of thinking in schools where words have right and wrong definitions. This practice of authorized meaning is even extended to the body as students must raise hands, remain in seats, keep eyes on the teacher, line up to go to lunch, and wear particular clothes or suffer the ideological meaning consequences.

Words are the most malleable of signs, but our common social practice is to interact and negotiate until we can denote a specific meaning. As we write, we use redundancy, modifying adjectives and adverbs, conditional phrases and clauses, in an attempt to cut off tangents to say what we mean. Yet, every word is full of connotations, and we often don’t mean what we say. As a result of our social interactions in multiple groups and contexts, every sign offers unlimited potential meaning when we reframe it from the social relations of another context. Metaphor is a concept that recognizes the unlimited potential meaning of each and every sign. Yet, metaphors can become overused in social interaction and become dead such as “table legs,” or cliché such as “fish out of water.” That signs can yield unintended, multiple, even subversive meanings is also a way of thinking internalized from social interactions in which our initial meanings are challenged, or are set in humorous play, depending upon the social relationships at work.

Language as a system of signs, and a way of internalized thinking, tends toward the construction of dyadic meanings, perhaps in part, because language as a tool is most powerful in organizing social activity when actors assume to hold the same meaning for a linguistic sign. Eco (1984) asserts that linguistic signs “are not based on the model of inference but on the model of equivalence. Aristotle was in fact the first to insist that linguistic terms are equivalent to their definitions and that word and definitions are fully reciprocal” (p. 29). Equivalence characterizes our common practice with language, even when we enter into debates about the correct meaning for a word or definition of an object in the world. Equivalence even extends to our negotiation of meaning for non-linguistic shared experiences, as we turn to language to discuss our responses to art, music, movies, dance, a party, or any lived event/activity. “Language is a primary modeling system, through which the other systems are expressed” (Eco, 1984, p. 32).

A model of equivalence in which meanings are dyadic between a SIGN and its OBJECT is precisely the internalized model of interpretation that critical literacy practices attempt to transform. It is a dominant social practice to socially construct and accept static and transcendent sign meanings that can be easily defined, described as a unitary whole, taught or transferred, and judged as to the extent that each iteration of the sign with another person, place, or time aligns with the convention that has been established. And it is precisely the affordances of written alphabets and print to represent language, and the means of mass reproduction and distribution of representations that has supported the social practice of dyadic equivalence across time, space, and culture, as well as between students and teachers in education. Street (1995) argues that changing this literacy practice must begin early in external social interactions of school:

Every literacy is learnt in a specific context in a particular way and the modes of learning, the social relationships of student teacher are modes of socialization and acculturation. The student is learning cultural models of identity and personhood, not just how to decode script or to write a particular hand. If that is the case, then leaving the critical process until after they have learnt many of the genres of literacy used in that society is putting off, possibly forever, the socialization into critical perspective. (p. 140)

The value or desire for power in a social context also contributes to how particular signs come to hold specific meanings that constitute the available hierarchical identities and relationships in a community that embraces a dyadic model of equivalent sign meaning. Critical literacy practices seek to make explicit how such dyadic meanings are constructed by examining the negotiation of signs in social interactions with questions such as: “How might this sign mean something else in reference to a different time, place, or intention?,” “Whose interests are served or ignored in this representation?” and, “What values and beliefs might explain why the actors embrace this particular meaning?”

Our compulsion towards convention in dyadic literacy practices does not eliminate the unlimited possibility of invention. Perhaps invention has been more evident in non-verbal sign systems of representation and communication, such as art, music, and dance. However, “a linguistic term appears to be based on pure equivalence simply because we do not recognize in it a ‘sleeping’ inference” (Eco, 1984, p. 35). It is these hidden inferences that suddenly appear when we say something that had no intention to harm yet produces in response hurt feelings. It is also these underlying inferences that we attempt to mask, control, or keep hidden, when we design a political message in our community. It is then, precisely these sleeping, underlying, disguised, ignored, inconsistent, or despised inferences that critical literacy practices seek to make visible as the shaping referents or context for the meaning of a message that must be explicitly discussed to examine the ideological consequences for identities and relationships desired in a community.

This compulsion towards convention in dyadic literacy is perhaps even more evident in EFL practices as the use of standardized forms of English and the meritocracy of high-stakes testing dominates EFL curricula in Korea and other Asian nations (Pederson, 2019; Shin, 2010; Stein & Newfield, 2006). This autonomous from of literacy tends to stifle critical thinking and limit a greater understanding of the creative potentials of language use and interpretation (Street, 1984), as well as limiting a greater understanding of the target culture (Shin, 2010). It is clear that the dominance of GTM and ALM methodologies in EFL curricula function as autonomous forms of literacy, and thus, do not generally allow for Vygotsky’s (1981) theories of learning through social interaction and by doing that many progressive second language educators believe greatly facilitates learning (Lantolf, 2000; Morgan & Ramanathan, 2005). As such, EFL students are constricted to the boredom of rote learning, or banking education (Freire, 1970), that not only stifles greater engagement in learning but also retards creativity and the goal of gaining greater fluency in the target language (Lantolf, 2000; Pederson, 2019; Shin, 2010). In addition, traditional dyadic methodologies typically used in Korean EFL classrooms do not follow the dictates of the current Korean National Curriculum that calls for student-centered classrooms, communication, the application of knowledge to context, and creativity (Pederson, 2019).

2. The Triadic Sign

When we always recognize that each SIGN has an OBJECT meaning only with respect to an underlying inference, a third component, then we begin to explicate the ideologies that frame our interpretations of texts. Pierce defines the sign as “something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity” (Eco, 1984, p. 14). The respect or capacity of a sign constitutes how that sign fits within a meaningful context of ideas, values, beliefs, and purposes—a third sign that Pierce named the Interpretant. Through symbolic interaction, we negotiate conventional meanings that attempt to fix, or control, these interpretants so that signs, especially language signs, can function as tools to achieve the pragmatic goals of a socially valued activity. Just as a sign is not inherently dyadic in meaning, a sign is never static in the triadic relationship of the sign, object, and interpretant. “In truth, the sign always opens up something new. No interpretant, in adjusting the sign interpreted, fails to change its borders to some degree” (Eco, 1984, p. 44). In fact, a sign is full of potential meanings because it can have an infinite number of interpretants, all of which layer the sign with different meanings, each with a social purpose or ideological direction when those meanings are wielded in social interaction.

Identifying the sign’s potential meanings is a central activity in the study of literature in school, a literacy practice in which students search for symbols and metaphors, and connecting themes, that will transform a linguistic text into a great work of literature. The identification and discussion of intertextual links between signs within and beyond the text is an inquiry into interpretants that generate powerful hidden meanings. However, this inquiry often takes the character of a dyadic practice when the meanings of the signs and their interpretants are pre-authorized by literary experts and communicated through the power of the teacher in the classroom social context. This dyadic form of literacy is also indicative of common EFL methodologies given the domination of GTM and ALM in EFL practices as well as the power of the meritocracy of high stakes testing in Korean education (Shin, 2010). This again highlights how the meanings for signs become authorized in practices that have more to do with power relationships than with inquiry into representations of human experience. Again, the dyadic model of equivalence guides the external social interactions and becomes reinforced as an internal way of thinking in a non-critical literacy practice.

The triadic thinking sought in critical literacy practices is similar to what Pierce defines as semiosis. While meaning seems to be contained within a triadic sign, it quickly relies upon and moves into an array of signs that juxtapose other multimodal signs from texts and life experiences. “If the sign is not a three-term relation based on the structural centrality of the interpretant, it fails to be a sign and cannot account for semiosis or for inquiry” (Freadman, 2004, p. 118). The movement among signs is so instantaneous and infinite that segmentation and reification of sign meaning becomes an understandable aspect of symbolic interaction in order to actually use signs as tools to accomplish and negotiate intersubjectivity and shared activity. But, it is a fundamental premise of Pierce that all thought is in signs, perception is nothing but signs in relation to other signs, and representation is our only reality.

When semiosis asserts that signs have object meanings that are mediated by interpretants, it does not mean that physical objects, including words or gestures, are experienced empirically. The object itself is a sign. The object is the first intention of a sign’s meaning and this first intention is embedded in a model of equivalence in which signs are dyadically associated with their object meanings. Interpretants open up the meaning between a sign and its object because it causes us to realize that the first intention is a representation itself, thus the object is a sign for another object and interpretant, and so on. Pierce relates that each interpretant is a second intention, or inference that in adjusting the meaning of the triadic sign, itself is a sign that is open to further thought in the direction of equivalence or inference. “Finally, the interpretant is nothing but another representation to which the torch of truth is handed along; and as representation, it has its interpretant again. Lo, another infinite series” (Freadman, 2004, p. 12). Thus, Pierce asserts that the social world abounds with signs.

Before going further, it is critical to distinguish two uses of the word “sign” in this article. At times, “sign” has referred to a symbol, or object, or word, or gesture–some experienced sign that has an intended object meaning and interpretant inference which themselves are signs. While this description is helpful in describing the structure of a sign, such relationships within the sign of its interpretant can give the impression that signs exist as separate and intact entities of an empirical reality or phenomenological experience. A sign is always a triadic entity; a sign always consists of a sign, object, and interpretant. A sign that only has a sign and object in some dyadic relationship of meaning does not exist; the interpretant is just sleeping or has yet to be considered or recognized. A sign that is only a sign cannot exist because it would not even be perceived until it is brought into relationship with two other signs, the object and interpretant. This should make sense with regard to perception, as we often do not initially notice some signs in an experience because we did not bring to bear interpretants that would have generated, or mediated, a particular object signification. Thus, the world is full of potential signs, but we only think within the flow of those that have triadic relationships. This flow is semiosis.

This lack of semiosis would obviously be more the case with second language learners who have an incomplete understanding of specific signs in the original language. Applications of semiotics to critical literacy in EFL practices would greatly expand student understandings of the possible meanings inherent in triadic approaches to signs as, by definition, critical literacy seeks to uncover not only the specific ideological meanings encoded into texts by the producer, but to also situate the sign into various contexts to see how it may be transformed for the purposes of greater social agency and justice (Freire & Macedo, 1987; Giroux, 1997; Luke, 2012). Clearly, the inclusion of this form of critical literacy into EFL practices would be of great benefit to student learning as it would necessitate student-centered practices, group and class discussions, increased critical thinking and creativity, as well as promoting greater fluency and understanding of the target culture. Finally, such pedagogical initiatives would also invite, if not necessitate, the inclusion of multimodal texts within EFL practices in ways that would not merely treat them as additional texts for a dyadic understanding of language but would invite differing student interpretations of the signs within these texts (Jewett, 2007; Kress, 2000).

III. SEMIOSIS WITHIN CRITICAL LITERACY PRACTICES

Semiosis is a social practice, a way of using signs that directs interpretation towards a model of equivalent meaning, a model of inferential meaning, or a balance between the two depending on the desired goals, identities, and relationships in the particular interpretive community. This pragmatic framing of semiosis is central to Pierce’s goals in identifying the underlying structure of logic and inquiry as acts of representation that are accomplished by signs in sequence with signs in ways that construct different types of thought. Pierce proposed three broad classes of signs, the icon, index, and symbol to explain the primary relationships we make between a SIGN-OBJECT-INTERPRETANT in order to accomplish thought and social action. Freadman (2004) describes these three classes of signs drawing examples from Pierce’s collected papers:

The ‘mediating representation’ is the interpretant; the mechanism described thus far does not make the difference between icons and indices on the one hand, and symbols on the other. All are representations, and hence, all are of the ‘third’ category. Peirce moves, therefore, to make distinctions within this category. The distinction he makes is this: those representations ‘whose relation to their objects is a mere community in some quality’ are termed likenesses (=icons); those ‘whose relations to their objects consists in a correspondence in fact’ are termed indices; but those ‘the ground of whose relation to their objects is an imputed character’ are called symbols (W 2:4, p. 56). The three classes are distinguished by the grounds of their claim to be representations, and to be representations of what they represent. Only one ground is of relevance to logic: it is ‘imputation,’ that is thought. (p. 12)

Thought is generally understood to be inner speech, composed of linguistic signs that bear an arbitrary relationship between word and meaning. And it is precisely this arbitrary, or imputed, relationship that embodies ideological INTERPRETANTS that mediate meaning between a SIGN and its OBJECT. “Taxes” is a word that does not have a static or reified meaning but is a site of struggle within a social practice. Different interpretants can be brought to bear on the linguistic sign to generate connotations that each fit a different set of values and beliefs about the relative good of taxes. Logic would involve developing the sequence of signs that would align interpretants to support one ideological perspective about taxes and minimize the involvement of other ideological perspectives by cutting off differing interpretants through a move towards an equivalent meaning in the object.

Icons and indices are relevant within each social practice because these two classes of signs bring us as close to the apprehension of reality as semiosis allows. While symbols, predominately as linguistic signs, are negotiated in the balance between convention and invention, they do not have any claim to empirical or palpable reality. The word “cup” does not look or sound like the any number of possible objects to which it might refer, just as each physical cup may have characteristics that imputes a cup for travel, for tea, of a wealthy person. However, a photograph or a drawing of a cup, although stylized by an artist, does share a quality of likeness to the cup. This Iconic relationship is often used in the production of signs as a representational practice that helps identify the characteristics of an object that are relevant to the pragmatic purpose of the symbolic representation. Also, with pragmatic intentions, indices establish causal relationships between signs. A broken cup on the floor is a sign of a fall from the counter, an object meaning made possible by interpretants from experience with witnessing the drop of objects with similar qualities. The exact cause of the fall remains a sign without an object, and many possible interpretants; it could be the cat, an earthquake, a tussle between children who quickly disappeared.

Together, the juxtapositions of signs as icons, indexes, and symbols allow us to represent and communicate our experience in the physical and social world. They give us the sign tools to hypothesize causes, compare and contrast qualities, invent patterns and names, and negotiate the control of meaning that regulates our own and others’ lives. To wield signs with agency and consciousness we must take up the interpretants in our semiotic practices. Iconic and indexical relationships provide important connections to our perceptual world; however, symbolic relationships construct our ideologies, our logics that frame through ideological interpretants the factual meanings that we come to attribute to iconic and indexical signs. Critical literacy practices intentionally seek to explicate the possible interpretants for deliberation, debate, and transformation. The critical quality of a literacy event can be analyzed by identifying the sign relationships as icons, indexes, and symbols, and using these relationships to juxtapose signs in ways that intentionally take up for critique the underlying interpretants. Thus, the practice of critical literacy conforms to the current Korean Ministry of Education’s English Curriculum in that it encourages communication between teachers and students, promotes critical thinking, seeks the situating of knowledge to context, and promotes the creativity of thought and action (Pederson, 2019).

Given a triadic understanding of meaning, and critical literacy as the intention to take up or consider the interpretants that mediate potential object meanings for signs, we can examine the sequence and juxtaposition of signs in a multimodal text and evaluate the degree to which their design brings interpretants under critical reflection. It is helpful to understand the sequence of signs as falling into Pierce’s (Freadman, 2004) broad classifications of icons, indices, and symbols. Iconic and indexical juxtapositions most often reify the object meaning by their characteristic purposes of defining the qualities of an object and setting objects into cause-effect relationships that represent empirical experience. With iconic juxtapositions, the signs share key qualities of the same object meaning. With indexical juxtapositions, the signs are connected as facts of nature without pushing a consideration of why or how such a connection came to be a commonly held belief. Iconic and indexical juxtapositions rarely raise questions about the hidden underlying interpretants. Thus, the greatest potential for the critique of interpretants involves symbolic juxtapositions in which the sequence of signs force a consideration of the sleeping inferences and the beliefs and assumptions upon which meanings are based.

Metaphors are a prime example of semiotic juxtapositions. While the term metaphor is most often contextualized within a practice of literary analysis, the relationship established between two distinct signs with different object meanings is characteristic of everyday semiosis. To say that a child flies through the room mediates the activity of the child (the SIGN) through an interpretant characteristic of another sign such as a bird and plane. The child is not literally flying. In mediating the child’s activity as flying, the underlying interpretant becomes available for critique: Is it acceptable for this flying, or do certain cultural beliefs, values, and expectations need to be examined to modify or resolve meaning for the action and its interpretation. This particular metaphor and many similar to it might be rather commonplace and do little to prompt examination of underlying ideological beliefs about the events being represented. In fact, this particular metaphor may be rather iconic and indexical as it connects two signs based on shared qualities about movement in a cause-effect empirical world. It does not raise questions about the underlying interpretants of either sign as a consequence of the juxtaposing metaphor. Differences in the quality of metaphors are often at the heart of literary analyses as readers of great literature identify those powerful metaphors in a work of art that push at the deeper themes and issues inferred in the transaction. Symbolic juxtapositions, far more than iconic and indexical, open up the signs being related in a metaphor so that previously assumed cultural values and beliefs of deeper structures can be explicated and critiqued.

It is necessary to now turn to the analysis of examples to further clarify and define the utility of semiotics for the assessment of critical literacy in multimodal texts. In the analysis of multimodal juxtapositions of signs, the guiding questions are:

1. Is the juxtaposition, or sequence of signs, an icon, index, or symbol? Icons represent a shared quality. Indices represent a correspondence in fact. Symbols represent an imputed character.

2. Does the juxtaposition emphasize the object meaning, or does it open up an examination of how the sign might have different meanings, or questionable meanings, when mediated by different interpretants?

We begin with the analysis of a video poem written by a 7th grade student in an American English class entitled “Just People” (see Figure 1). This video poem was made by an individual student in an English unit on poetry. The project portion of the unit followed the major pedagogical stages of critical literacy which included the group discussion of texts and their meanings, in which triadic interpretations of signs would occur, the brainstorming and discussion of individual project topics, the creation of the video representation, and its presentation to the class.

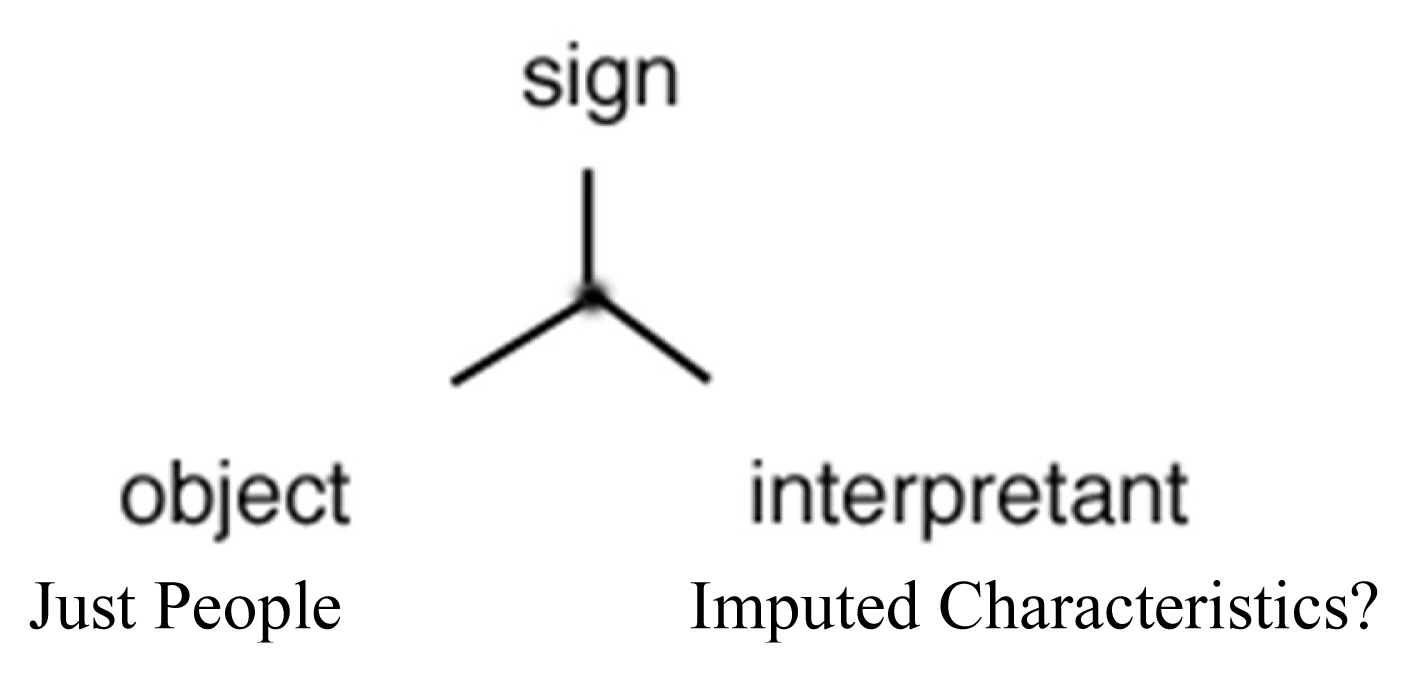

The poem title juxtaposes the idea of “people” with “just,” immediately inviting an inquiry into what interpretants might mediate people as “just people.” This juxtaposition is symbolic and critical. “Just” does not have a set of qualities or characteristics in common with “people” so the juxtaposition is not iconic. “Just” does not signify some factual correspondence of cause or consequence with “people;” therefore, it is not indexical. “Just” mediates “people” by symbolically asking what interpretant signs would define or impute the characteristics of people who could be signified as “just.” The imputed character of people as mediated by the juxtaposed sign “just” functions critically because it invites the exploration and critique of the imputed characteristics that might be valued in people who are “just people.” It can be helpful to diagram the sign to visualize the semiotic mediation generated in the juxtaposition. As discussed above, the title would look as follows (see Figure 2):

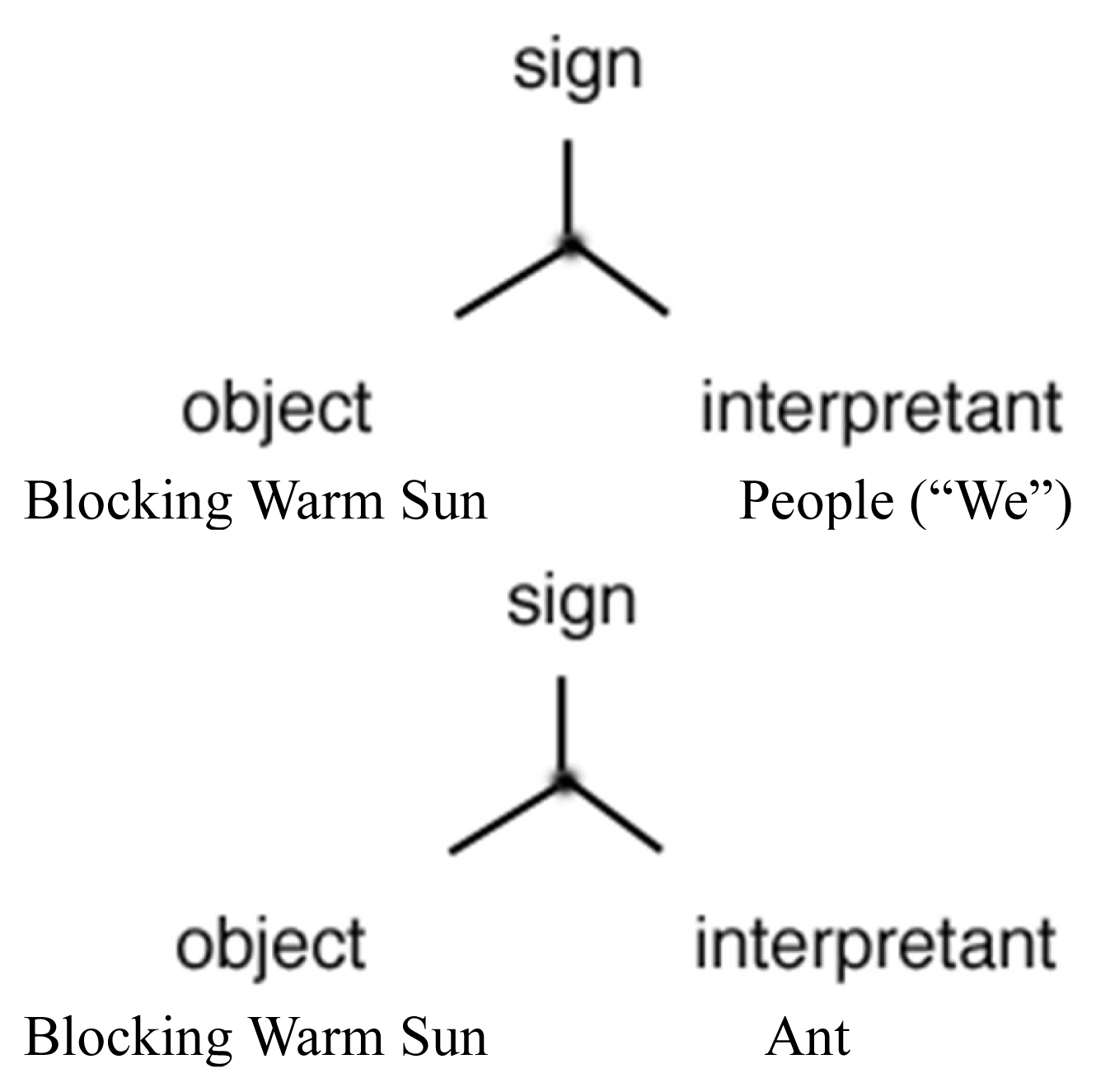

When we move to the sign sequence of the multimodal poem, however, the juxtapositions become primarily iconic and indexical in character and do not, until the very final image, take up interpretants that might mediate, thus critique, the imputed character of “just people.” The first two lines of the poem juxtapose people, as “we,” to “a cat” and “giants.” A cat is used as the interpretant for an indexical relationship between people and giants, as both exhibit the “towering” consequences of their relative size. Giants are towering with respect to people, and people are towering with respect to a cat (see Figure 3).

The towering consequences of a giant are not critiqued, explored, or questioned, nor are the towering consequences of people over a cat; thus, the interpretants are not being engaged in any critical inquiry, but merely function as an indexical link between two sign relationships (giants to people & people to cats) that both have the same consequence in fact (towering).

The juxtaposed images likewise do not open any critical exploration of the signs or object meanings, but merely present iconic representations of a cat and a giant. Of course, the particular image of the particular cat and particular giant used in this design could open up critique of underlying interpretants about why that rendition of a cat or giant; but, the design of the poem does not take up any critique of those image choices and their potential mediation of “cats” and “giants.” They are used in the design as iconic signs.

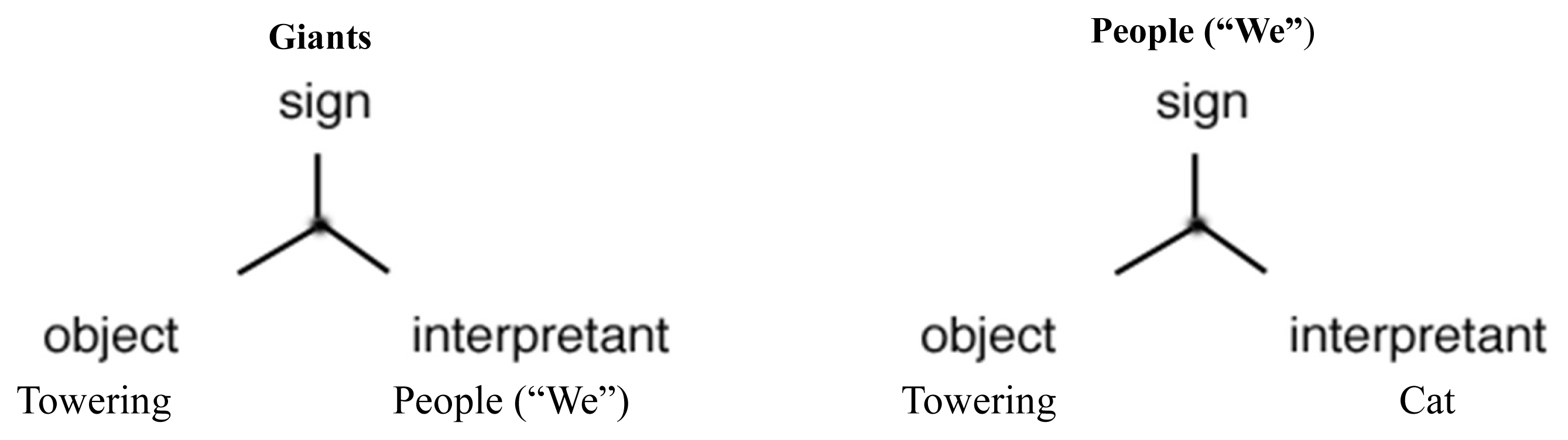

This pattern of indexical and iconic signs is repeated in the next sequence of signs in the poem: “To an ant, we are mountains blocking the warm sun.” (see Figure 4)

Here, we have displayed the triadic relationships of the signs to illustrate how the “mountains” signify “blocking the warm sun” when mediated by “people,” and how the design of signs in the poem then turns this interpretant into a sign for the repetition of the same indexical consequence for ants. “Mountains” and “we” both signify an indexical consequence of our relative size in blocking the warm sun. Likewise, the juxtaposed images of the ant and a mountain function within the semiotic design of this poem as iconic signs that do not critically take up the interpretants that might question the representations and consider alternatives. The image juxtapositions emphasize the first intentions of the signs’ objects, simply an ant and a mountain.

Something interesting happens in the third sequence of the poem, “To a shark, we are dinner just waiting to be eaten.” The juxtaposition of the words alone do not suggest more than an indexical relationship between people and sharks in that one common consequence of putting the two together is a dinner for the shark (see Figure 5).

No critical intention appears in the design of this juxtaposition as any issues related to people being dinner are not focused within the interpretant of sharks’ habits, habitats, or interactions with humans. Yet, the juxtaposed images for this sequence of words does generate a humorous reversal that reframes the three signs and their relationship. The first image of the shark during the lines “to a shark,” is clearly iconic as it emphasizes the object meaning of the giant fish. The second image of a dinner plate with a portion of fish juxtaposed with the line, “we are dinner waiting to be eaten,” intentionally contradicts the words by making the shark dinner for people (see Figure 6).

The sign and interpretant instantly flip back and forth as meaning must simultaneously deal with both people and sharks as potential dinners and diners. Here the author demonstrates some ability to wield symbols to at least manipulate the interpretants, even if there is little interrogation of how or why those interpretants frame a particular object meaning. While this may not be a stunning critical examination of the representations of sharks, people, and their relationships in the world, the designed reversal is characteristic of much humor in which the punch line of a joke reframes the sign-interpretant relationship. Satire, of course, uses this technique of reframing the familiar to generate humor that exposes the interpretants for a critique in which they seem ridiculous in the exaggeration.

As the video poem ends, the last sequence returns to examine what it means to be “just people.” The words, “To another person, we are just people” are juxtaposed with an image of a smiling elderly man tipping his cap on a beach with the ocean in the background. He has a walking stick, brown pants, light collared shirt, dark v-neck sweater, and a dark casual suit jacket; his cap is a European beret; his arms are widespread with a welcome hug for the viewer (see Figure 7).

Why is this image “just people?” The interpretants that mediate the object meanings of “just people” in this design are not interrogated through the indexical and iconic juxtapositions, but an inquiry into the imputed characteristics, or symbolic juxtaposition, represented by each small aspect of the man in the final image is at least activated. In that small degree, the interpretants are on the cusp of being taken up and made visible, and the final juxtaposition might be considered critical, at least in its potential to open up a negotiation of what constitutes any shared values for “just people.”

The second example that helps illustrate the use of semiotic analysis to assess critical literacy examines a video essay titled “Communities Coming Together” authored by a small group of 8th graders in response to a prompt to describe what creates a sense of community. The pedagogy of this example also followed Freire’s (1970) schema of critical literacy as it included the reading of a text, situating it into differing socially relevant contexts through individual inquiry, group discussion, brainstorming and discussing possible topics, constructing the video representation, and presenting it to the class. As part of the pedagogical design of this project, students were also explicitly asked to include at least one instance in their video when words, images, and or music were juxtaposed to work against each other in the meaning. The reader should immediately recognize that this pedagogical element is based directly on the idea being put forth that critical literacy involves the intentional use of juxtapositions to make underlying interpretants visible and available for critique.

“Communities Coming Together” is a 2:18 video that is divided into two halves. The first half of 1:20 is composed of 14 images that use text overlays to identify various interpretants about how communities are created. Each text overlay generates an inference beyond the object meaning of the image alone that intentionally explores a second intention of the image representation to signify a type of activity that creates community belonging. The very first image of the film is of two hands, one black and one white, shaking hands. The letters of the title drop in over this image to read “communities coming together,” and the Beatles’ song “All Together Now,” plays in the background. This juxtaposition of image, text, and music generates an interpretant that when different races come together in a solid handshake, then the community is coming together. The relationship of these three signs is symbolic, rather than indexical or iconic, and as a symbolic juxtaposition, it generates some critical thought about the interpretants that mediate meanings about how the signs can represent ideas on community. The music would not alone suggest the second intention of bringing races together, so does not have an iconic relationship to the image of an interracial handshake. The handshake might indexically point to the consequence of the overlay text “communities coming together,” but it functions more as a symbol that takes up interpretants about the necessary condition of race relations in a community that has come together. After this juxtaposition, the first half of the video offers a series of juxtapositions of images, text, and music to explore additional activities that create community togetherness.

The second juxtaposition is more iconic in function, as it presents the image of a house in winter with holiday decorations juxtaposed with the overlay text, “Holidays and Celebrations.” The text is basically a label for the image, a sign reifying an equivalent meaning with the object meaning of the image, thus it does not take up any interpretants for critical consideration. While the song, “All Together Now,” continues to play in the video, its juxtaposition does not offer any strong critical exploration of how the image might stand for aspects of community belonging.

In the third image of the video, a similar house decorated for Christmas with two children caroling outside is juxtaposed with the text, “Holidays make people happy, bringing families and neighbors together for celebrations.” While the image alone signifies cultural traditions of holiday decorating and activity, the text explicitly takes up interpretants that mediate holiday signs as a representation with second intentions of bringing families and neighbors together. The text pushes the image, music, and words into a symbolic juxtaposition that has a degree of critical examination of the potential interpretants of the signs.

The video continues in a similar fashion with some images juxtaposed with words that function simply as iconic labels, and others with words that push the juxtaposition to consider how the activities and events represented in the images might also have the second intentions of creating some aspect of community belonging. The sixth image of a protester holding a sign and mouth open yelling is juxtaposed with the text, “Fighting for what you believe in.” While this is an apt iconic juxtaposition that labels qualities of the scene in the image, it is also functions as a symbolic juxtaposition within the sequence of the video to mediate the act of protesting as a community building. The thirteenth and fourteenth images of soldiers and a young child inside a house is juxtaposed with the text, “If a community can live through war, it will bring its citizens closer together,” and “People fighting together can build a close bond to form a community.” These symbolic juxtapositions take up the potential interpretants of an image to consider critically how acts of war might actually mediate a sense of belonging in a community.

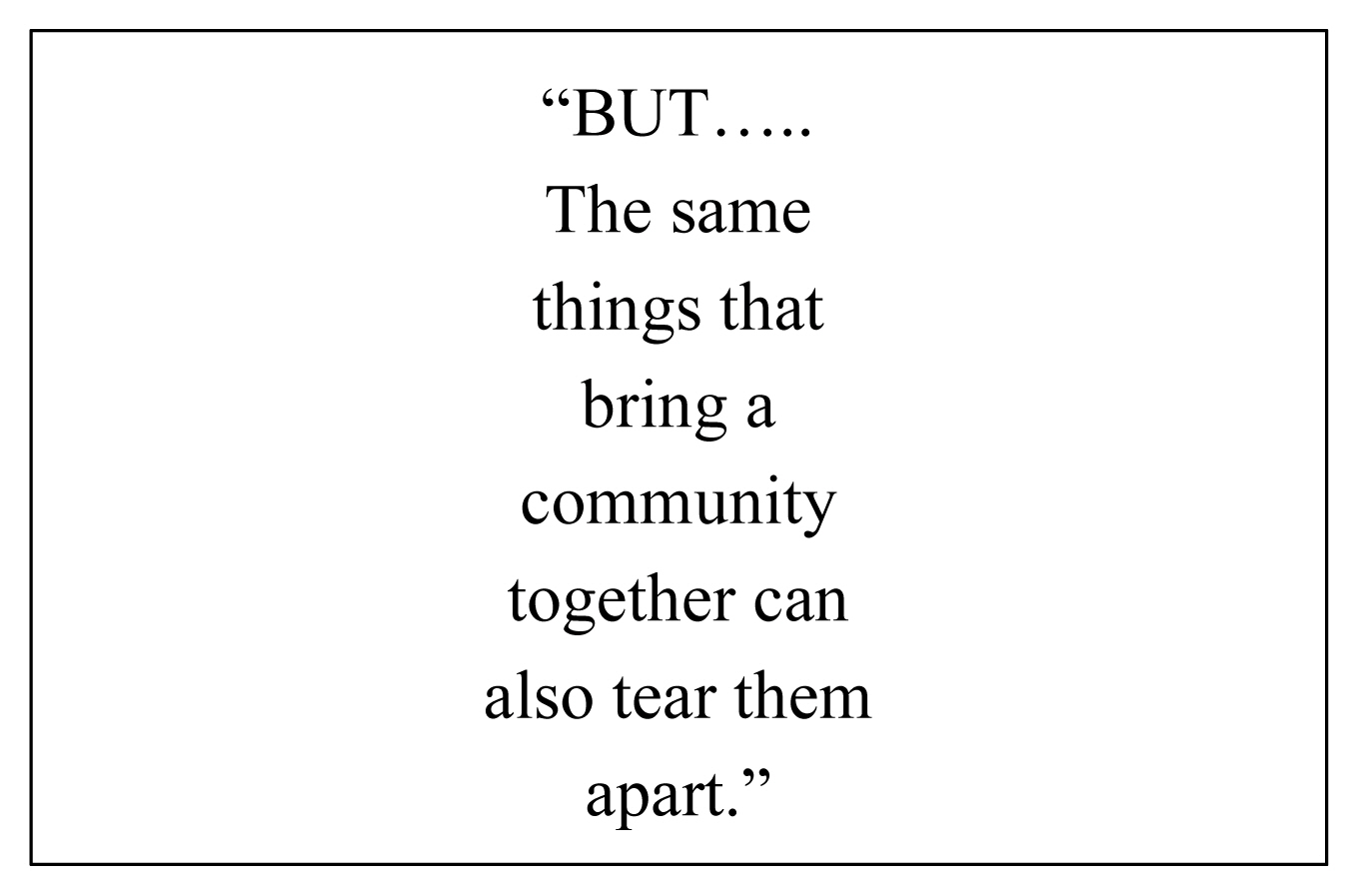

At this point the movie goes to a black screen, the music changes from the upbeat Beatles to the eerie introduction of the hard rock song “Crawling” by the musical group Linkin Park (2000), with the scrolling text (see Figure 8).

The loud hard rock music alone would not signify a community tearing apart, but juxtaposed to the words on a black screen, a symbolic relationship is designed to introduce an alternate explanation of how the same images signify separation and division of community in second half of the video.

In this second half, just 5 images are reused from the first half of the video but juxtaposed with different overlay text. The holiday image is juxtaposed with “Some people are scared and separated by religion barriers.” So, the juxtaposition of this image in the first half of the video generated underlying interpretants of bringing family together at the holiday, now takes up the potential second intentions of dividing people who do not share religious beliefs. The sixth image of a protestor is juxtaposed with, “Being on different sides of an issue can create hate, which can tear communities apart.” The eighth image of a man and a child in front of a school bus and the twelfth image of a solider in desert uniform is juxtaposed with, “Sometimes people who have experienced war feel apart from others which can sever the ties that bind them.” And the fourteenth image of soldiers in a home is juxtaposed with, “War tears people on opposing sides apart, no matter how close they once were.” Each of these juxtapositions of image, overlay text, and discordant rock music creates a symbol that opens up the potential underlying interpretants for critical examination, specifically with regard to the second intentions of the symbolic juxtapositions to mediate understandings about things that bring a community together and tear a community apart. The authors of this video engaged in design work that made extensive use of symbolic juxtapositions to create opportunities for critical literacy.

Although these examples were taken from two American English classes engaging in the creation of video representation projects, they nonetheless demonstrate how such pedagogy may be applied to Korean K-12 English classrooms. As multimodal pedagogies are growing in Korean EFL classrooms (Kress, 2002; Park, 2020; Pederson, 2019; Royce, 2002; Van Leeuwen, 2015), a more clearly defined semiotic nature of critical literacy would equip teachers with the necessary tools to make their practices not only more engaging to the students, but more significant as well, particularly in terms of developing critical thinking skills. In addition, the use of student made video representations is growing within the EFL community (Akdeniz, 2017; Chen, 2018; Hung, Keppell, & Jong, 2004; Naqvi, 2016; Nikitina, 2009; Pederson, 2018: Puspa, 2016) While the comparison is stilted in terms Korean students understanding of, and facility with the English language, Korean students are certainly endowed with the same capacities for symbolic thought, curiosity, creativity, and critical thinking. Finally, as the generally autonomous nature of the literacy practices in Korean English classrooms stifles motivation and engagement in classroom activities (Shin, 2010), it is likely that they would welcome the opportunity to engage in these learning practices.

IV. DISCUSSION: SIGNS WITHIN CRITICAL LITERACY PRACTICES

Roughly speaking, semiosis follows a pattern of signification that enacts the valued activities in a social practice. When social/cultural practices employ print, visual media, and linguistic symbols to accomplish their pragmatic goals, they can be called literacy practices. For the purpose of understanding interpretive activity that can be characterized as part of a critical literacy practice, semiosis can enact a model of equivalent meanings through an emphasis on the OBJECT relationships, or a model of inference through inquiry into the INTERPRETANT relationships between signs.

Semiosis that involves conventional meanings through an equivalent object, or the invention of new meanings through inferential interpretants, lies at the foundation of many theories about meaning and interpretation. Friere and Macedo (1987) assigns two key functions to language; first, that it allows us to live “in” the world, and second, that it allows us to live “with” the world. As we use language to live in the world, we rely on conventional object meanings as the first intentions of signs. When we are mis-understood, we may laugh or cry at the inference, but to accomplish our “in” the world activities, we negotiate some conventional shared meaning that establishes equivalence between the SIGN and its OBJECT. Simultaneously, INTERPRETANTS allow us to live “with” the world, thus every symbolic interaction gives us the opportunity to reflect on our representations and the identities and relationships produced by that particular use of language in that moment. These identities and relationships are inferences that we can adjust to the degree that we can contest, negotiate, or transform the first intentions of the language signs by making the inferential frame more visible. I contend that for Freire (1970), conscientization reflects a dialectic between our use of language to be simultaneously “in” and “with” the world, and that this dialect seeks balance in order to construct a sense of power and agency in our use of signs and their use on us.

Fecho, Davis, and Moore (2006) attribute a similar dialectic between language as convention and invention in their description of Bakhtin’s (1981) definition for heteroglossia:

Bakhtin used heteroglossia to describe an ongoing transaction between centripetal, or unifying forces of language, and centrifugal, or diversifying forces of language. On one hand, the centripetal forces, largely through dominant social control, are constantly trying to stabilize and ultimately reify language. On the other hand, the centrifugal forces, primarily through personal interpretation, are always diversifying language, possibly to the point of anarchy. Neither extreme is desirable, and Bakhtin argues that it’s the balance of these tensions–their points of transaction–that makes for a healthy, living language.

(Fecho et al., 2006, p. 190)

Semiosis that continuously and exclusively pursued the inferences would be similar to a student in a classroom that continuously makes tangential remarks; while some would be humorous and enlightening, if taken to an extreme a sense of purpose in constructing some shared representation of experience can be lost. Likewise, the dyadic sign with its overwhelming emphasis on the reified OBJECT meaning can stabilize meaning, but only through some measure of social control, such as a grading system that reinforces particular meanings, or the more subtle positioning afforded identities that also carry the INTEPRETANT signs of privileged race, class, or gender in a cultural practice.

Heteroglossia as a balance between convention and invention echoes Rosenblatt’s (1978) theory of reading as a transaction between the reader and the text guided by two dominant stances, the efferent and the aesthetic. In the efferent stance, readers seek a meaning that can be broadly shared as denotative for the text; this is a negotiation of equivalence between a SIGN and its OBJECT meaning accomplished by implicit or explicit agreement for INTERPRETANTS that conventionalize meaning. In the aesthetic stance, readers have a unique “poem” or OBJECT meaning for the text that reflects their particular inferences in a specific time and place. Every reading of the same printed text produces a new intertextual array of inferences drawn from life and all other texts–a new poem–that is defined as a largely personal interpretation totally unique to oneself and others. However, Rosenblatt also believes that these “poems” are not so far into the realm of personal invention as to prevent readers from negotiating the best or most likely meaning for the text through the transaction between efferent and aesthetic stances; a literacy practice in which readers’ meanings are taken back to the text for justification acceptable to the social group.

It is important to recognize that the many definitions of critical literacy discussed earlier above also reflect an underlying dialectic or transaction between the text, the reader, and the interpretation, or response. Some critical literacy practices place an emphasis on the identification of ideologies within the text, suggesting that some words or symbols represent underlying perspectives that can be deconstructed and exposed for the values they constitute for social identities and relationships. Some of the critical literacy definitions focus on the reader, or interpreter, and the cultural background and life experiences that shape any meanings for the text. In these conceptions, the ideology that the reader carries into the text must be uncovered. In addition, some descriptions of critical literacy focus on how the reader’s response can initiate an inquiry into the interpretants of the text and the interpretants of their experience that transact through the response to negotiate the ideologies of both text and reader. The signs of a response open up the interpretants of the text and the reader, thus balancing a critical examination of meaning that avoids essentializing ideology in the conventions of a text or the inventions of a reader.

Within language arts classroom, within both native English-speaking nations and EFL nations, transmediation has also become a popular activity in which students produce a new multimodal text to communicate a meaning from another text. Drawing a picture of a scene from a novel, juxtaposing images to the lines of a poem, creating a dance to signify a character’s emotions at a particular moment in a story are all examples of transmediation. Siegel (2006) explains how transmediation of meaning across sign systems generates reflection on the underlying interpretants that carry ideological beliefs for signs commonly coded within their usually experienced sign system.

When a learner moves from one sign system to another, semiosis becomes even more complex, in that an entire semiotic triad serves as the object of another triad and the interpretant for this new triad must be represented in the new sign system. And, because no pre-existing code for representing the interpretant of one sign system in the representamen of another sign system exists a priori, the connection between the two sign systems must be invented. This is how transmediation achieves its generative power. (p. 70)

While juxtapositions across sign systems potentially open up the underlying interpretants for examination and critique, it is also possible for transmediations to simply reify assumed meanings for a juxtaposed signs in both sign systems. Unless the transmediation generates the question, “Why does this image also represent the idea in the lines of the poem?” or “Why does the meaning of this song in juxtaposition to this image, adjust my initial meaning?” then the transmediation does not take semiosis into reflection on the underlying cultural ideologies that mediate our meanings for all signs.

Signs are tools that help us to accomplish valued social activities. The common characteristics of critical literacy define texts as ideological, meaning as culturally mediated, identity as socially constructed, and an awareness of these as necessary for the conscious control of language in interactions to produce a greater sense of freedom (agency) and social justice. This is somewhat foreign to the manner in which textual meaning is constructed in school classrooms, where words have right and wrong definitions, and interpretive discussions are embedded in a discourse of getting the meaning desired by the teacher/test and unlocking the meaning within the text as intended by the author. Street’s (1984) distinction between autonomous and ideological definitions of literacy is especially useful in understanding how the purposes and functions that texts serve are themselves culturally determined as ideological practices, and not inherent or autonomous psycholinguistic practices (Scribner & Cole, 1981; Siegel & Fernandez, 2000). An understanding of all meaning as semiosis in triadic sign relationships, and a distinction between sign relationships as icons, indices, or symbols, provides a semiotic tool to design and analyze juxtapositions of signs to generate reflection on, and critique of, the underlying ideologies that mediate (and contest) meaning in our multimodal lives. An analysis of semiotic juxtapositions not only explicates claims of critical literacy but embodies the semiosis that constructs a critical literacy practice in social interaction as well as inner thought. It has been shown how critical literacy and the use of multimodal texts can facilitate the learning, motivation, creativity, and understanding of the target culture of EFL students (Chen, 2018; Hung & Huang, 2015; Jewett, 2007; Kress, 2000; Naqvi, 2016). Nonetheless, however useful the theories and pedagogies discussed in this paper may be, Korean English teachers in training are generally not exposed to these ways of viewing and using language.

V. CONCLUSION

The pedagogy illustrated in this paper reveals how the juxtaposition of triadic signs serves as a beginning to critical thinking and thus is useful to, and a foundation of, critical literacy. Of course, the students in the classes mentioned were not introduced to semiotic theory, but just prompted to use some of the contents of their video projects to be at odds in meaning, which necessarily opened a space for critical thinking in the classroom. Clearly, such pedagogy is not difficult to implement for teachers who already utilize multimodal projects as part of their teaching practice, whether in English education, EFL, or any other language classroom genre. Using such pedagogies, students may develop their critical thinking abilities to begin to apply them to the social world in order to begin to see how representations of meaning, in all forms of textuality, serve to both structure and maintain the structures of society that sustain the social inequalities among race, class, gender, and sexual orientation. The development of such critical thinking leads to Freire’s (1970) concept of conscientization where students begin to see and better understand how they were and are socialized into their values, beliefs, and ideologies and that their social positioning in society was not a matter of chance. More to the point is that the development of these skills allows students to consider how to enhance their social agency, and those of the people of their discourse, to enhance their social mobility, increase social justice, and strengthen the democratic principles of their society. Of course, critical literacy and semiotics are not a panacea for a society’s ills. Nonetheless, Freire’s concept of publishing, where students are encouraged to disseminate their projects in some manner, is perhaps more hopeful with the increased potential to signify their multimodal meanings through the various platforms available through modern ICT. Finally, in order to utilize such pedagogies in EFL classrooms, it is necessary for Korean teacher education to expose teachers in training to the basics of semiotics, critical literacy, and sociolinguistics, which is currently not being generally done. The authors hope that the guidelines within Korean National Curriculum may in time reconcile this issue for the benefit of its students and their society.