A Study of the Effects of Transmedia Storytelling on Active Participation and Language Learning*

Article information

Abstract

This study observed the following two purposes: (1) to investigate whether transmedia storytelling (TS) encourages beginner-level college students to actively participate in classwork, and (2) to determine whether TS is positively related to second language (L2) learning. The transmedia approach will help the students to gain more knowledge and information about the target language. Two beginners were invited to act as case studies to these ends. An American television series, The Good Place (Holland, 2018), was chosen. This study was conducted in three stages: (1) participant presentations on selected topics via TS, (2) first recall test (one week later, with notice), and (3) second recall test (two weeks later, without notice). On the first test, Participant A scored well on his selected topic, but his score dropped somewhat on Participant B’s topic. Participant B had a better score than Participant A on both topics. The second test was an error analysis. Participant A had minor errors on the TS-based topic but significant ones on the not-TS-based topic. Participant B had fewer errors than Participant A on both topics, and all his errors were minor. Both participants were involved in active participation. Pedagogical implications are discussed in the conclusion.

I. INTRODUCTION

The number of college students registering for language classes that use film as a medium for instruction attests to the popularity of this pedagogical method1. It can be argued, however, that this method removes active participation from the classroom; students just sit back, relax, and enjoy watching films.

The 21st century requires modern teaching methods that take a student-centered approach (Andrade-Velásquez & Fonseca-Mora, 2021). Teachers are no longer treated as the retainers of knowledge (Amon, 2019). Rather, educational empowerment becomes an important concept. In the classroom, a teacher shares “responsibilities with students, autonomy, and a voice in decision making process” (Gómez et al., 2015, p. 169). Additionally, as the 21st century has come to be known as the digital era and contemporary students as “digital natives” (Prenski, 2001, p. 1), education specialists have been hurrying to develop relevant and suitable teaching methods (Balaman, 2018). Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory (SCT) supports student-centered education; according to this theory, children learn to participate in activities as individuals rather than as students. From an early stage, they experience the world and acquire conscious control as agents. Self-regulation is one of conscious control (Dongyu, Fanyu, & Wanyi, 2013; Lantolf & Thorne, 2007; Lantolf, Thorne, & Poehner, 2015; Ohta, 2017; Swain, Kinnear, & Steinman, 2013). All the literature places a common emphasis on more socially-oriented approaches to second-language (L2) learning. That is, it views students as citizens and underlines the importance of individuality in L2 learning, thereby encouraging student-centered approaches to teaching.

This paper presents transmedia storytelling (TS) as a student-centered concept. Most of the contemporary literature argues that TS encourages reluctant students to actively participate in classroom activities and is positively related to L2 learning. However, TS is technically mediated interactivity (Kern, 2014); it differs from face-to-face encounters in many ways (Chen & Wang, 2008; Jenkins, 2006; Kappas & Krämer, 2011). Furthermore, its effectiveness and the ways in which it affects L2 learning have yet to be determined (Andrade-Velásquez & Fonseca-Mora, 2021). This paper, then, investigates the possibilities TS presents for students’ active participation and successful L2 learning. Beginner-level college students were invited to participate in the study, and the one’s who are not interested in learning English are likeliest to present two problematic characteristics as learners: reluctance and slowness. The study made use of films, as all films tell stories—which is a distinctive characteristic of TS. Memorization and recall were used for evaluation. These are basic factors but are considered appropriate for beginners. Language items in a film are not used for educational purposes, but for entertainment purposes. So in this study, memorization and recalling were enough for the participants.

The following section describes the concept of TS and examines the relationship between the use of TS and language learning. The necessity of applying TS in the educational context, in particular, is discussed, along with the degree to which TS and language learning are related. The third and fourth sections of the paper examine, through the relevant case study, the extent to which students’ active participation is possible with the use of TS, as well as whether this relationship is positive or negative. The reactions of the study’s participants to TS are then discussed.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

1. What is Transmedia Storytelling?

Transmedia storytelling can be regarded as the telling of a story from different perspectives using different platforms for collecting relevant information (Andrade-Velásquez & Fonseca-Mora, 2021). According to the scholar who introduced TS, media users see themselves as active and creative participants (Jenkins, 2003). Fleming (2013) states that:

We might define transmedia learning as: the application of storytelling techniques combined with the use of multiple platforms to create an immersive learning landscape which enables multivarious entry and exit points for learning and teaching. It is the unifying concept of the learning environment that is important since that can become a landscape for learning that has few, if any, boundaries. With philosophical underpinnings in constructivist and connectivist theories, a transmedia pedagogy uses technology in an integrated way that allows learners and content to flow seamlessly across media platforms. (p. 371)

According to Fleming (2013), the 21st century is characterized by an influx of information from everywhere. Language users make meaning or construct their own meanings from this influx. Also multivarious information should be connected in an integrated way. TS is one way of achieving this. Gambarato and Tárcia (2016, p. 6) identify three main features of TS: 1) multiple media platforms, 2) content expansion, and 3) audience engagement. Most authors agree on the importance of both content expansion and audience engagement, making it clear that the mere telling of a story across platforms does not qualify as transmedia. Jenkins’s (2006) answer to this is convergence, which refers to the flow of content across multiple media platforms. A film, for example transforms into a book, a game, and mobile media. This is a creative phenomenon that goes beyond simple storytelling. But it is at the center of media. This is transmedia storytelling (Kalogeras, 2017). Jenkins (2007) also argues that TS is a process whereby essential elements of a narrative are systematically spread across multiple delivery channels, thus creating a unified and well-organized entertainment experience. In principle, each medium makes its own special contribution to the development of the story.

One important feature of TS is that it does not only involve telling a story about characters; rather, it also involves creating a story about various fictional worlds. Consequently, the interrelations of the characters and the stories are well supported (Jenkins, 2007). It is one of attractions to scholars and educators. McAdams (2016) notes the following:

If the traditional logic of the media was to produce cultural content, on a specific platform, for users to consume (unidirectional model of traditional television, for example), now people have been massively incorporated into the role of content producers, and move from one media platform to another [...]. Put another way, people no longer observe what happens in the media, but can play an active role in its production [...]. In fact, for over a decade, more than half of adolescents and young people (part of the generation called millennials) [...] have been creating cultural content through digital media, and a third of Internet users share the content they produce. (pp. 10–11)

In this comparison of the media’s traditional logic with its new logic, McAdams (2016) emphasizes that TS is not simply storytelling but is, rather, story creation across several media.

2. Is Transmedia Storytelling Related to Second Language Learning?

In the context of education, it is sensible to assume that TS can motivate L2 learners to actively participate in classroom activities. TS supports L2 learning, in particular, literacy in the following sense:

Engaging with transmedia literacy requires students to develop technological proficiency, analyze multimodal texts, and collaborate with others to create new knowledge through the negotiation and synthesis of various content. Not only this, but transmedia stories provide a unified narrative through which students can develop these literacies. The narrative of the transmedia story provides a scaffold for students, through the overlapping story content, as they develop new literacies. (Roccanti & Garland, 2015, p. 19)

Because TS involves creating a unique story rather than simply telling an existing one, L2 learners are required to gather information through various platforms or media. This process makes learners focus on new information and actively engage in transmedia literacy. The idea is that at the center of TS there is a narrative, or a story; through collaborative work, learners construct their own stories. However, this does not say anything about L2 learning, and is insufficient to developing language learning. Rather, TS seems more fitting to general first-language (L1) education. TS’s focus on narrative appears to be excessive. Raybourn’s (2012, p. 471) idea that TS leads to “engaging students emotionally in their learning and involving them personally in the story” is unrelated to L2 learning.

Recent literature has blown a fresh breeze into the field of second-language education. Andrade-Velásquez and Fonseca-Mora (2021) emphasize that L2 learning is a complicated process and that active, student-centered learning overcomes its complications. The following provides insight into the 21st century classroom:

English language learning, in the mediated and participatory landscape of the 21st century, can no longer be narrowed down to the exploration of the four skills: speaking, listening, reading, and writing. Competence in ESL entails not only grammatical but also communicative, symbolic, and relational aspects which are controlled by sociolinguistic, pragmatic and cultural variables. Hence, language practice cannot be dissociated from the students’ needs or language use, goals and reflections. (Rodrigues & Bidarra, 2017, p. 2)

Rodrigues and Bidarra (2017) contrast the sole emphasis of traditional teaching methods on language skills with the expanded emphasis of new teaching methods on sociolinguistic, pragmatic, and cultural variables; teaching methods move from linguistic matters to social matters. However, the authors do not mention language itself. As far as second language is concerned, matters such as language awareness, attention, salience, etc. should be explicitly mentioned. It is agreed that TS is a dramatic technique mainly employed in fictional dramas (Ajala, 2020), but TS research should address the question of what role TS narratives play in second-language learning.

The following summarizes Rodrigues and Bidarra’s (2017) application of a narrative to the ESL context. The authors conducted a pilot study among 24 tenth-grade students at an urban school in Portugal. The first repetition of the narrative was carried out in three 90-minute sessions. The students worked on tasks and activities related to the narrative. In this session, students explored the narrative without the teacher’s help, and it was checked how much time they spent searching the various platforms of the narrative world. During the second session, the teacher asked the students to select one of the available posts and hand in a digital object related to it. Furthermore, the students discussed what they had learned through searching the posts and the digital object. In the third session, the students participated in one of the main characters’ adventures, paying attention to the whole experience of the narrative world.

Rodrigues and Bidarra (2017) entitled the resulting paper “Toward a Transmedia Learning Approach in ESL Context”. As noted above, they discussed a transmedia matter, not a language matter. In this sense, current transmedia-related work is not ready to improve language skills using narratives or stories.

III. METHOD

1. Purpose

The purpose of the case study outlined in this paper was twofold: (1) to suggest a way of encouraging L2 learners to actively participate in movie-based English classes, and (2) to investigate the relationship between active participation and English-language learning. The case study made use of the concept of transmedia storytelling. Each participant in the case study picked a topic (i.e., a characters, an event, etc.) from an assigned episode of a television series. The participants then developed their own stories with reference to resources from diverse platforms.

2. Material

This study made use of the comedic fantasy television show The Good Place (Holland, 2018, season 3, episode 1). It aired on September 27th, 2018, in the United States. This series was chosen because its main characters are distinctive and its events are unusual; therefore, it was thought that the show might give the participants ideas for topics.

The third season begins when Michael, a character who was originally an antagonist, suddenly changes for the better. From the beginning he says to Judge Gen, “I still believe that they would have become good people if they’d just gotten a push in the right direction […].” Michael is referring to four other main characters: Eleanor, Chidi, Jason, and Tahani. And it’s clearly the best way to see if bad people can become good without knowing anything about what’s waiting in the afterlife. The judge agrees with Michael and orders him to create a new timeline for the four other characters. No more intervention is allowed.

3. Participants

There were two participants in this study: beginner-level college students with TOEIC scores under 400. Both had some experience studying English through films. Although the participants are beginners of English, they have already watched the season 1 and 2 with subtitles. This experience will help the students in transmedia storytelling. For example, Participant A chose the character Chidi as a topic, his reason being that “Chidi was always logical while talking and that he had reasons even he made a trivial choice. Also Chidi often used quotes and examples and never tire of keeping doing this. Such things made me curious of Chidi.” Participant B picked Michael based on this character’s conversation with Judge Gen. Selecting the topics are one of the key points of transmedia storytelling. Participants with background knowledge of the subject will help them selecting the material. In this sense, the current participants were well selected for this study.

4. Procedure

First, a teacher explained to the participants what transmedia storytelling is and how to collect information for storytelling. Second, the teacher assigned a viewing of the aforementioned episode of The Good Place to both participants. The participants watched the episode and chose topics for storytelling without the teacher’s help. Despite the limitations of their language abilities, the participants were able to follow the content of the episode thanks to the help of captions. It is important to note that this was both participants’ favorite television series, thus they had previous knowledge of the story. Third, each participant submitted his presentation material to the teacher (see Appendix) and shared his topic with the other participant. It means that one topic was related to TS, the other topic was not related to TS. The participants presentation utilized transmedia to search for cultural background or character analysis. For example, when searching for character analysis, students will pursuit in different digital platforms and with the information the participants will add their own thoughts and develop the knowledge of the character. The presentation will cover the procedure of how each participant searched for the chosen topic.

Next, the participants gave presentations, with an allowance for using both English and Korean languages due to the fact that they were beginners. Two tests were then administered to both participants. Each participant was expected to memorize and recall his own topic as well as the other participant’s topic. Finally, the teacher analyzed the participants’ presentations.

5. Evaluation

This case study consisted of one observation and two tests. In the observation, the teacher observed how the participants prepared their presentations, i.e., their strategies for incorporating TS. The teacher had to evaluate whether these strategies were relevant to language learning. If the strategies were well organized and resulted in positive language learning, TS was thought to influence language learning.

Scores were unnecessary in this stage; rather, it mainly measured the subjects’ degree of active participation. The teacher simply compared the two presentations, regardless of how the participants used TS. Since they used various platforms, it presupposed that the participants performed iterations of the episode. The teacher looked at how many platforms the participants used and decided whether the platforms functioned as windows for language input. Active participation was considered a good reflection of language input.

The first test in the second stage involved recall, and was administered one week after the participants’ presentations, with advance notice. Appendix 1 and 3 were scenes selected by the participants, more specifically the scenes were recall of their own and others content. In this test, recall speed and number of errors were measured. Each participant was expected to recall his own topic faster than the other participant’s topic. If this assumption turned out to be correct, TS could be considered relevant to language improvement. It was also expected that there would be fewer errors on the TS-based topic than on the non-TS-based topic. If, in turn, this assumption turned out to be correct, TS could likewise be considered an effective vehicle for language learning.

The second test in the third stage was similar to the first one and was administered one week after it, this time without advance notice. The test’s questions on language items were the same as in the first test. After the test, an error analysis was conducted. That is, the results of the second test were analyzed. Errors on the TS-based topic, such as errors in the use of function words, were expected to be minor; most function words do not impede an understanding of content (Learning English, 2021; Nordquist, 2020), as they express grammatical relationships and have little lexical meaning (whereas content words carry clear meaning and are key to understanding [Beare, 2020; The Sound of English, n.d.]). If errors on the TS-based topic were mostly minor, TS would be thought to support language learning.

There was one important condition underlying the study. If either participant was to successfully recall both the TS-based topic and the non-TS-based topic, it would be concluded that TS is not at all relevant to language learning. As demonstrated in the literature review, current TS studies do not show a clear and explicit relationship between TS and second language learning, so this case study is very important.

IV. RESULT AND ANALYSIS

This section analyzes the participants’ degree of active participation in their tasks and aims to determine whether there is a positive relationship between the storytelling approach and language learning.

1. Types of Strategy

Participants took a storytelling approach to gathering information and organizing their presentations. They collected information from similar platforms, such as movie clips, captions, and Google search, but they organized this information in completely different ways.

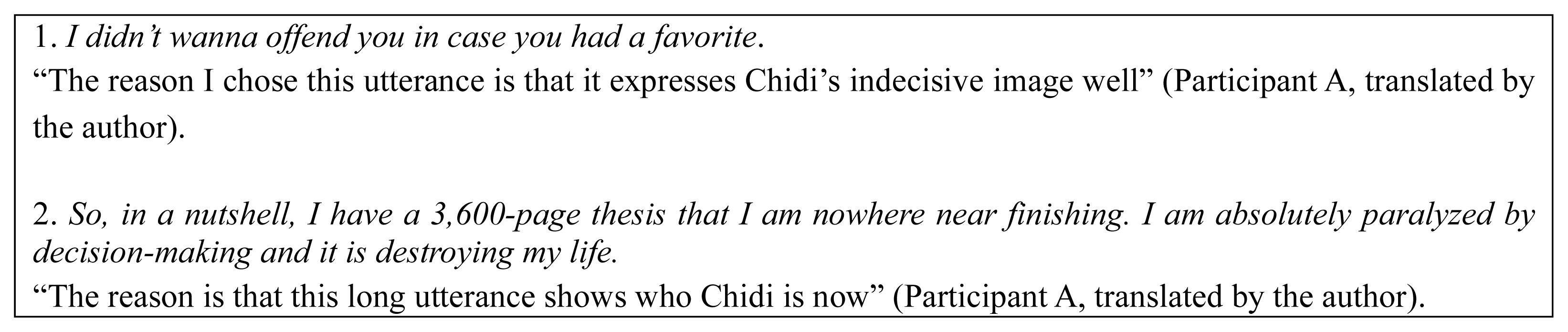

Participant A organized information by reading all the captions relaying utterances about the character Chidi in the aforementioned episode of The Good Place and making a list of Chidi’s qualities. He then selected a number of utterances and expressed his reasons for choosing them. In this process, Participant A demonstrated active participation. He put together his story without the teacher’s help. Considering his lack of English-language competency, this accomplishment was significant. Figure 1 shows examples of Participant A’s strategy.

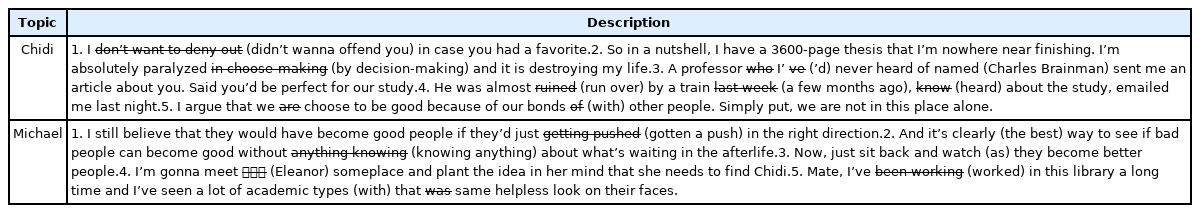

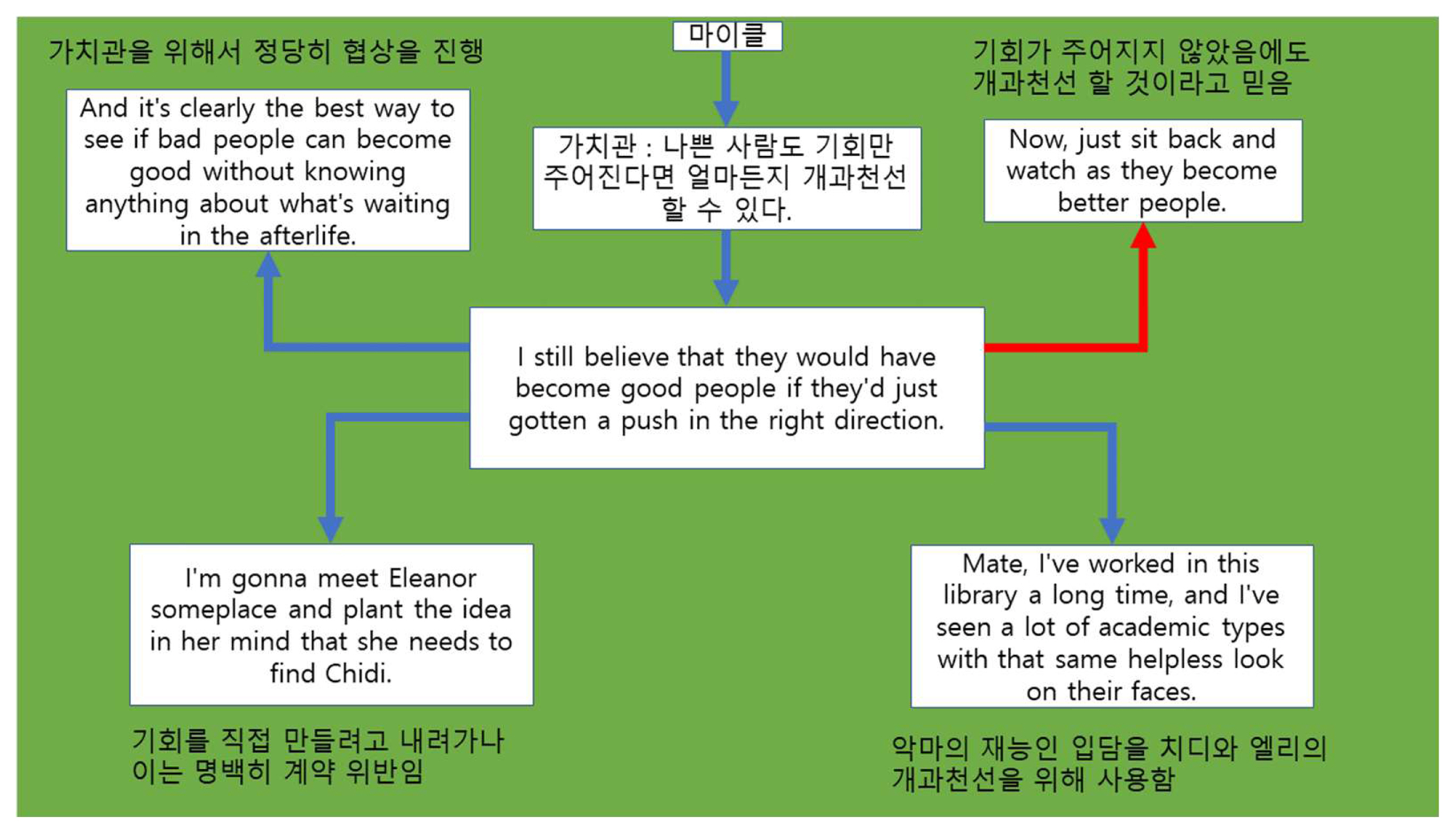

Participant B used a combined visual and cognitive strategy for organizing his ideas, i.e., a graphic organizer. He depicted Michael’s character in this graphic organizer, focusing on the character’s values as expressed through five utterances (see Figure 2).

Participant B’s Presentation Material Based on TS

Note. 가치관을 위해서 정당히 협상을 진행: (Michael) negotiates his values (with Judge Gen). 가치관: He believes that bad people would have become good people if they’d just gotten a push in the right direction. 마이클: Michael. 기회가 주어지지 않았음에도 개과천선할 것이라고 믿음: (Michael believes that) bad people can repent without being given chances. 기회를 직접 만들려고 내려가나 이는 명백히 계약 위반임: (Michael) goes to Earth in an explicit breach of his contract. 악마의 재능인 입담을 치다와 엘리의 개과천선을 위해 사용함: Michael uses his gift or evil and his skill at talking for Chidi & Eleanor’s repentance (Participant B, translated by the author).

2. First Recall Delayed Test

Since it was believed that each participant took more time to prepare his topic, it might influence recall speed. In accordance with the assumption that each participant would better recall his own passages than the other participant’s, Participant A was better at recalling his own passages (“Chidi”). He took almost half the time to recall Chidi’s passages that he took to recall Participant B’s passages (“Michael”). Furthermore, he made few errors on Chidi’s passages. By contrast, he received help from the teacher twice and made two minor errors in recalling Michael’s passages.

Participant B, on the other hand, was better at recalling Participant A’s passages (“Chidi”) than his own (“Michael”). He received help from the teacher and took 20 seconds longer recalling Michael’s passages. When asked why this happened, Participant B confessed that he had been very nervous in recalling “Michael” because it was his first time. By the time he got around to “Chidi”, his nerves had settled. He did not consider his use of a graphic organizer relevant to his memorization or recall of language items.

In general, Participant A performed well on his own topic, and Participant B had good recall test results for both his topic and Participant A’s; the Participants’ results are summarized in Table 1, below. However, the storytelling approach did not guarantee recall even though it was successful in inducing active participation.

3. Second Delayed Recall Test

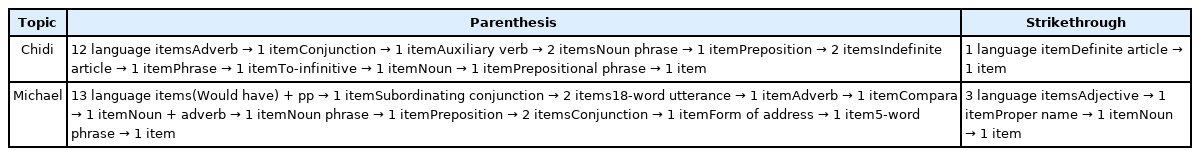

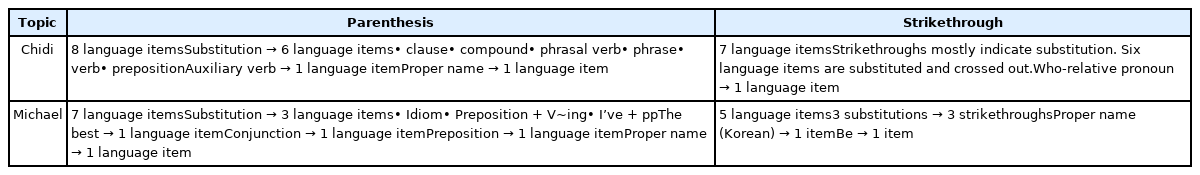

The second recall test focused on what kind of errors the participants made. Analyses of these errors are presented in Table 2–5.

Table 3 describes Participant A’s errors in detail. The participant made twelve errors on his own topic (“Chidi”) and thirteen errors on Participant B’s topic (“Michael”). He did not appear to have an advantage on his own topic. However, a closer examination of these errors revealed significant differences between topics: All 12 of Participant A’s errors on his own topic were minor. They did not reflect a lack of understanding of the meanings of the utterances. By contrast, his errors on the topic of Michael indicated that he had difficulty extracting meaning from the utterances. First of all, the types of errors Participant A made here were different from those he made on the topic of Chidi, the latter being typical of L2 learners. His errors on “Michael” were unusual and complicated, and could not be categorized as regular grammatical terms. For example, he failed to recall an 18-word utterance. It could not fit into grammatical categories. Also his errors were mostly grammatical.

Here, then, Participant A’s errors were significant. In this regard, storytelling influenced his errors. The strikethroughs indicate that he omitted the relevant language items because he lacked knowledge of them.

Table 4 consists Participant B’s error analysis. The strikethrough portion are the errors made by B and the was edited to show the original version of the conversation. B has chosen Michael as a topic, but more errors were shown in Chidi’s conversation. This result indicates that the Participant’s attention had a positive impact in memorization and shown less error during recall. On the other hand, Chidi wasn’t B’s topic and has shown lack of attention which resulted as more errors during recall.

Table 5 shows that Participant B’s error types were completely different from Participant A’s, depending on the topic. For “Chidi,” Participant B made eight errors, which were represented by more complicated grammatical units. Most of his errors on both topics involved substituting the correct language items with incorrect ones. Four of his errors were minor ones. None of these errors on either topic impeded his understanding of meanings. Participant B made a roughly equal amount of errors on his own topic (seven errors) and on Participant A’s (eight errors). This implies that his errors were not influenced by storytelling.

In sum, Participant A was influenced by the storytelling approach. Participant B was not influenced, even though he gave a brilliant presentation with a colorful graphic organizer. Thus, while transmedia storytelling can be said to have encouraged active participation, its relationship with language learning remains uncertain.

V. CONCLUSION

Current movie-based English classrooms have faced two difficult problems. One is that EFL learners sit back and watch movies but do not actively participate in learning. The other is that teachers are uncertain about the relevance of movies to language teaching and learning. This paper has dealt with overcoming such problems. Transmedia storytelling has been imported in this paper in that current literature has supported a combination of active participation and language learning through TS (Andrade-Velásquez & Fonseca-Mora, 2021; Kern, 2014; Kramsch, 2009; Rodrigues & Bidarra, 2017).

The present study investigated whether TS would be effective in supporting both active participation and language learning. Regarding active participation, both beginner-level learners organized their presentations using various platforms and without their teacher’s help. They watched the assigned episode on their own and found relevant things to say about their topics. Though they were beginners, they depended on platforms (English and Korean).

The results were different with regard to language learning, however. On the first recall test, Participant A performed well in recalling his own topic but was slow in recalling Participant B’s topic. In this sense, TS was effective for Participant A. Participant B did excellent work in recalling both his topic and Participant A’s topic; TS did not seem to influence his recalling.

On the second recall test, both participants’ results were almost the same. Participant A made minor errors on his topic but significant errors on Participant B’s topic, which made it clear that TS had helped reinforce Participant A’s learning when it came to his own topic. Participant B’s errors were not influenced by TS, as evidenced by the roughly equal number of errors on his topic and on participant A’s. Furthermore, all of Participant B’s errors were minor, which indicated that he had understood the episode’s content. TS, then, did not give Participant B an advantage on his own topic.

A possible pedagogical implication of using TS is that it could help some beginner-level students who have good memorization skills. Conversely, it could be meaningless for some students because it may proceed regardless of language learning. Students can prepare presentations with relative ease thanks to the existence of various media platforms. So, in order to improve students’ language abilities, teachers should administer language tests following the use of TS. Memorization and recall activities are good examples of the kinds of tests that can be used.

Notes

The statement was retrieved from a professor who has taught Movie English subject for over 20 years in a Korean university.