A Study on the Use of Preferable Textual Enhancement Techniques From L2 Learners in the Movie Before Sunset

Article information

Abstract

This study aims to examine whether textual enhancement (TE) saliency leads to second-language learning and to determine whether different types of TE influence second-language learning. The study invited three advanced level college students as participants using material from the movie Before Sunset (Linklater, 2004). In this case study, Participant A used an underline format, Participant B used a story map, and Participant C used a color-code format. They each had four tests (showing a TE strategy, form recalling, content remembering, and language completion rate). The results showed that each participant successfully used their individual TE strategy. Since Participant A primarily focused on language, his second test results were good, but his scores declined two and four weeks later. Participant C primarily paid attention to content; she performed well in a test relevant to the content but was the worst in language tests. Participant B performed the best across all tests because she focused on both language and content. This study suggests that attention is necessary for second-language learning, but that attention should be paid to form and meaning simultaneously. When it combines form and meaning, TE will be effective in second-language learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

A movie is full of attractive expressions that L2 learners would love to acquire. When language users talk, they want to express their feelings; if they talk without feelings, it does not feel like real talk. If you have some experience talking with native speakers, but fail to express your feelings while engaging in conversation, you may feel uncomfortable and lose confidence. Movie dialog is full of emotion because characters in a movie interact with other characters, expressing their emotions. This is why many L2 learners are attracted to movies.

Expressing emotions in L2 is probably one of the most challenging tasks for L2 learners (Dewaele, 2008; Fussell, 2002). Although L2 learners are familiar with constructing grammatically correct sentences in an EFL classroom, they rarely construct “emotional” sentences. If L2 learners want to construct emotionally resonant sentences, they should be treated as real people rather than just students. Furthermore, research on teaching materials and classroom activities to teach emotional expressions to L2 learners is insufficient. In this regard, a movie can be extremely useful in teaching and learning emotions for communication because although movies are fictional, they often show interactions between characters who behave like real people. Kim (2008) insisted that movies can be used by L2 learners to learn routines used in various emotional situations. Routines are not neutral expressions; instead, they tend to categorize language users in a target community. Routines convey emotion along with meaning.

Another challenging task is how emotional utterances or sentences can be dealt with in the classroom. When a teacher teaches English using movies, they must consider how they can help their L2 learners memorize any attractive expressions that convey various emotions and commit them to their long-term memories for communicative competence. Tomasello (2003, cited in Bybee, 2010) introduced a usage-based theory (UBT) of language acquisition in which grammatical structures come from language use rather than from innate structures, which leads to the integration of vocabulary and grammar. Selivan (2018) stated that “the blurred boundary between vocabulary and grammar refers to the tendency of certain words to occur with certain grammatical structures and vice versa” (p. 3). Specifically, UBT denies the language acquisition device (LAD), which was introduced by Chomsky (Shatz, 2007). Instead, it believes that language learning belongs to a general domain in the brain. In other words, language learning is similar to learning other subjects such as math, history, and geography. In UBT, grammatical knowledge is not primary, but actual language is. This is why UBT deserves special attention regarding the primary role of pragmatics in actual communication (Ghalebi & Sadighi, 2015): it regards actual utterances as primary sources for language input.

In the context of this theory, memorization is an important activity. Since a movie is full of real-life expressions, viewers cannot avoid memorization activities. Compared with generative grammar, in which the role of imitation in language learning is minimal and relatively unimportant, UBT is revolutionary (Bybee, 2010).

How can a teacher help their students improve memorization? There are two language teaching methods: explicit instruction and implicit instruction. First and foremost, current literature advises that explicit instruction is appropriate for a classroom setting (Andringa & Rebuschat, 2015; Archer & Hughes, 2011; Ellis, 2011). In addition, Archer and Hughes (2011) stated that explicit instruction is “systematic, direct, engaging, and success-oriented” (p. vii), and that evidence shows it raises students to a higher level.

However, movie English is somewhat different. In movie English, a teacher has to teach the storyline of the chosen movie because students are expecting it to be more entertaining than other regular English courses. Also, since a storyline provides the necessary context for language learning, the teacher must spend some time on story instruction, meaning that students should take some responsibility for grammar and vocabulary learning. In other words, students would more readily accept implicit teaching and learning in a movie English classroom. In addition, since movie English employs movie script reading, it is necessary to include textual enhancement (TE) such as bolding, underlining, and italicizing (KNLT, n.d.). TE functions by increasing exposure to the same target form and automatically making the language form more salient, thereby drawing students’ attention to the linguistic form (Stringer, 2018).

The case study investigates to what extent TE assists language learning in movie English. Sarkhosh and Sarboland (2012) mentioned that using TE might not be effective by itself, in that it does not matter which type of TE is used as bolding and underlining formats are not competitive, for example. They also mentioned that different types of TE have varying results in the noticing of linguistic forms. Therefore, this paper aims to determine whether TE or external agents are related to language learning and will also examine whether TE per se or language users who use TE will have more influence on language learning.

In a sense, language learning means form-meaning pairing. It implies that learners should pay equal attention to both form and meaning. Very often, L2 learners mainly focus on form to the detriment of meaning, while some learners tend to focus on meaning and ignore form.

This paper also investigates whether TE promotes awareness of form and meaning. In order to explore TE, three individuals will be invited to participate in a case study where each will be asked by a teacher to choose a different type of TE. Finally, this paper will observe whether the result of language learning is form-meaning pairing. Based on the results, we can determine whether the participants pay more attention to form or meaning, or whether they focus equally on both.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Limitations of Explicit Instruction

The extant literature indicates that “input enhancement refers to the process of making some linguistic forms more salient and noticeable in order to draw learners’ attention to them” (Bakhshandeh & Jafari, 2018; Sharwood Smith, 1991; Wong, 2005). The majority of the literature also suggests that explicit instruction is more effective than implicit instruction. For example, Macaro and Masterman (2006) investigated the effect of explicit grammar instruction on first-year students studying French at a UK university by focusing on grammatical knowledge and writing proficiency. The researchers tested an intervention group (n = 12) and a control group (n = 10) on three points (lowest, highest, and mean) over five months, and showed that explicit instruction led to improvements in some grammatical aspects. In addition, Spada and Tomita (2010) conducted a meta-analysis of 41 studies to examine the effects of explicit and implicit instruction in the acquisition of both simple and complex grammatical features of English. They collected data through a large-scale online search of the relevant literature and also investigated ten online journals.1 Their results revealed that explicit instruction helped control learners’ knowledge and unrehearsed use of simple and complex forms.

However, the literature also shows that L2 instruction needs a moderate amount of implicit instruction (Rogers, 2016). For instance, Fordyce (2014) examined the immediate and long-term effects of explicit and implicit instruction interventions on conversational English. The linguistic target of the interventions was the interactions between conversational co-participants. Researchers split 81 students of English at a Japanese university into explicit (n = 37) and implicit (n = 44) groups for three hours of instruction. The study gathered production data in writing immediately before the interventions and five months later. The results showed that explicit instruction was more effective than implicit instruction. However, both types of instruction were fairly effective for certain forms with specific functions, meaning that further research is required. In another study, Tode (2007) conducted an interesting experiment whereby he investigated the durability of the effect of explicit and implicit instruction. The participants comprised 89 Japanese junior high school students divided into three groups. The first group received explicit instruction about a rule of the copula be. The second group received implicit instruction whereby they memorized exemplars without depending on the rule. The third group did not receive any treatment regarding the copula be. The results indicated that explicit instruction was more effective than implicit instruction over the short term experiment but was less effective than implicit instruction over the long term.

In another durability study, Umeda, Snape, Yusa, and Wiltshier (2017) used three groups of participants to investigate the effect of explicit instruction on article semantics, targeting generic sentences. The first group was an instruction group, the second was a control group, and the third was another control group consisting of native English speakers. The results showed improved knowledge in the instruction group, but they had forgotten most of it after one year, which indicates an inability to maintain explicit knowledge. Hernández (2011) investigated the effects of explicit instruction, using a combination of explicit instruction and input flood. The result revealed that such a combination was not superior to input flood only. They found that the combination group’s learning outcomes were superior to those of the explicit instruction only group. Jones and Waller (2017) conducted an experiment examining whether explicit instruction only or a combination of explicit instruction and input enhancement produced superior vocabulary learning outcomes. However, both Leow (2009) and Winke (2013) investigated the effects of input enhancement on L2 grammatical development and found that while input enhancement improved noticing, it failed to promote L2 grammar without further explicit instruction. So he continued to say that it needs further research.

Teaching and learning movies are appropriate for implicit instruction (Explicit vs. Implicit Instruction for Second-Language Grammar, 2021). However, since movies contain many things to learn, explicit instruction alone cannot adequately cover both movie teaching and learning. One problem with implicit instruction is salience. In order to improve grammatical knowledge, salience should be treated well. So TE which belongs to implicit instruction will be introduced here.

2. Input Enhancement and Textual Enhancement

Input is a crucial component in second language acquisition (SLA) and is a key feature for language acquisition (Bayonas, 2017; Combs, 2004; UK Essays, 2021). Therefore, techniques or methods by which input is conspicuous have been introduced. One such technique is TE, which is part of input enhancement. TE appeared in the 1990s (Jahan & Kormos, 2015). TE is a type of input enhancement (IE) that makes the target language forms in the text more salient and is strongly associated with language learning (Sarboland, 2012). Moradi and Farvardin (2016) examined whether the L2 grammar learning outcomes generated by TE are superior to those produced by meaning-based output instruction. They found that the former was more effective than the latter. Jahan and Kormos (2015) define TE as follows:

Textual enhancement, which is a non-explicit and external input enhancement technique, was [ . . . ] an external attention drawing device whereby any particular feature of the oral or written input (e.g., grammatical items or structures, lexical or phonological items) can be made perceptually salient to L2 learners in a planned way so that they can notice the targeted forms without any explicit metalinguistic explanation. This input enhancement technique can be applied by teachers, researchers or material developers intentionally, in written or visual input, through typographical alterations such as boldfacing, underlining, enlarging, capitalizing, italicizing or colour coding. (p. 48)

According to Jahan and Kormos (2015), teachers use and introduce TE in implicit instruction through typographical alterations. However, TE can be explicit and internal IE from the learners’ perspective. Since a learner intentionally marks typographical changes on a target form, it can also be an explicit technique. Additionally, each learner possesses their style of choosing TE. For example, they can prefer underlining to italicizing. TE types are all visual techniques, although they seem mechanical. Erturk (2013) cautiously pointed out that visual techniques sometimes have no effect on the attention of L2 learners. Meanwhile, Leeser (2004) argued that TE has no effect on comprehension. The techniques cannot express people’s emotions or feelings. Certain learners can also use feeling-based IE. In this regard, TE is not a simple concept and most TE research relates to grammar learning from the teacher’s perspective.

One problem with using TE is that much of the current literature says that TE focuses on target forms. However, the main user of TE is the L2 learner. For example, if one learner uses the underline format, they underline linguistic forms. However, teachers do not always know why the learner underlines a particular target form. For example, do they underline in order to learn the target form, or do they underline for meaning? Combs (2008) stated the following:

We now turn to the third variable, processing for form and/or meaning. There is evidence that a learner’s cognitive processing system does not necessarily follow two discrete mental pathways (i.e., semantic and syntactic) but that the two processes overlap. Rather, individuals tend to take an integrative approach to semantic and syntactic processing. (p. 3)

Today is an integrative period; a dichotomy has faded away. Many of the current studies on TE mainly focus on grammar, but this phenomenon is like a trend because TE can target meaning and form.

Input salience, [ . . . ] can be created by an outsider (e.g., a teacher) or by an insider (i.e., the learners themselves). Learners possess their own natural learning and processing mechanisms which can, in and of themselves, generate input enhancement—so-called ‘internally generated input enhancement,’ which may or may not coincide with ‘externally generated input enhancement’ (as by a teacher or researcher). The learner’s mind, [ . . . ] is not singular or global, but rather modular in character; the learner has many minds—to use his term—vis-à-vis different linguistic domains and subsystems. Consequently, when exposed to externally enhanced input, learners (a) may or may not notice it, or (b) may notice it partially, contingent on whether or not they are ready for it or how much overlap there is between externally and internally generated salience. A mismatch may, therefore, arise ‘between the intentions lying behind teacher or textbook generated enhancement of the input and the actual effect it comes to have on the learner system.’ (Han, Park, & Combs, 2008, p. 598)

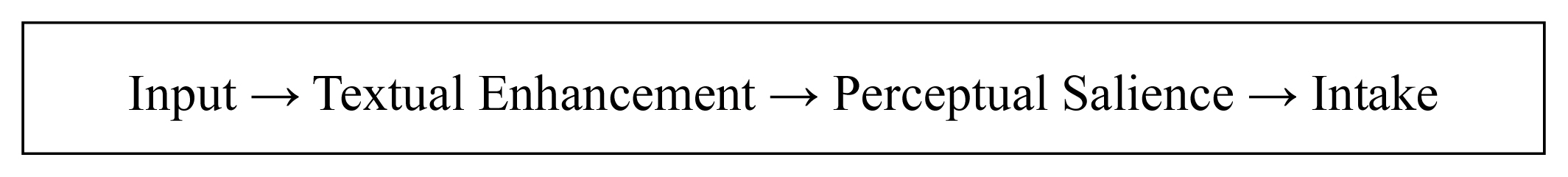

Finally, we need to discuss the merits of TE. Under TE, grammar instruction does not interrupt regular reading time in the classroom. Instead, traditional grammar instruction decontextualizes linguistic items from reading with a focus on forms (FonFs). For instance, in focus on form (FonF), a learner is aware of the meaning and use of targeted linguistic items (Long, 1991). TE is similar to FonF. Figure 1 describes the role of TE.

Figure 1 shows the importance of TE in that it absorbs input and makes it perceptually salient before changing the input to intake (Hernández, 2018).

III. METHOD

1. Goals

This experiment investigates L2 learners’ favorite types of TE in movie English. The L2 learners get to choose their favorite TE. However, the aim is to show the participants the use of various TE formats. Typically, the current literature refers to TE, input flood, and processing instruction as popular techniques (VanPatten, 1996, 2002, 2004). Although TE is a strategy mainly used by teachers to emphasize particular target linguistic features, in this study, TE will be initiated by the L2 learners rather than the teachers. Since film can provide a storyline of a movie and context for practical expressions, L2 learners can independently develop TE regarding forms (Sharwood Smith, 1993) or meanings (Lee, 2007). Therefore, this study aims to investigate L2 learners’ TE preferences and also to observe any relationships between L2 learners’ choice of TE and their language learning. In other words, the study examines whether learners’ choices influence their language learning. If their choice of TE turns out to not be related to language learning, what kind of factors involved with language learning will be examined instead.

2. Participants

Three advanced-level college students were invited to join this case study. Despite being asked to follow instructions, it is possible that their attitude might be passive even though they are highly advanced students. Because film provides attractive stories, the L2 learners might ignore any language-learning opportunities and would just sit back and relax. In this situation, if they do use TE types, then various aspects of their language learning will be observable such as active participation in movie-related tasks, the salience of linguistic items, and the organization of TE.

In this study, the teachers tasked the participants with the responsibility of picking interesting scenes from the movie before choosing one scene or topic to discuss further. Since this study focuses on types of TE, it was necessary to fix a scene for the sake of the experiment. All three participants achieved a good Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) score (range from 800–850) and had experience studying English with movies.

3. Materials

The text material for this study was the 2004 American romantic drama movie Before Sunset (Linklater, 2004). The main characters are Céline and Jesse, who happen to meet nine years after their first meeting in Vienna. They talk passionately about work and politics, particularly their past life, and find they are dissatisfied with their present lives. However, their romantic feelings for each other are gradually rekindled. In the movie, Céline keeps talking about the many aspects of her past life and dominates the movie with many beautiful lines. The way she talks is easily noticeable to L2 learners, whether in linguistic form or messages. This is why Before Sunset is an ideal study subject.

4. Procedure

Firstly, a teacher lectures about the relationship between improving TE and successful language learning (Stringer, 2018) and emphasizes why the use of TE is needed for enhancing language abilities. However, this kind of meta-language can be tedious for the participants, so the teacher keeps this lesson as short as possible. Next, the teacher and the three participants read the first part of the movie script together to develop a studious atmosphere before the participants read the rest of the script individually to save time rather than reading the entire script together. The participants then decide which part of the script will be the object of TE (see Appendix). As mentioned earlier, if several scenes are used in this study, the experiment will be very complicated. Each participant then hands in the task to show their strategy before participating in tasks (or tests) that last over one month. Finally, the teacher analyzes the entire task over the course of one month.

IV. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

1. Strategies for Textual Enhancement From Participants

Each participant favored a distinctive strategy to keep their attention on the target forms. Participant A used the “underline” format, drawing a line under a word, phrase, or clause to show salience, and primarily focused on linguistic items. Participant B focused on language and content and used a story map depicting the relationships between current events and Céline’s past life. Finally, Participant C focused mainly on meaning and used a color-coding format as an attention-grabbing textural technique. This study did not judge the participants’ techniques provided they were related to language learning. Thus, it was considered that such techniques without relevance to language learning were useless in EFL classrooms.

Participant A expressed his opinions as to why he would underline particular language items, primarily language items and secondarily content of the movie. Participant B constructed a list of sentences and vocabulary (language) along with a visual graphic display (content). Participant C highlighted message-oriented feelings within the movie using color-coding. However, they colored yellow over one big discourse, seemingly emphasizing the content of the movie clip rather than the language forms.

Each participant expressed their reasons for why they used their particular strategies. Furthermore, each participant demonstrated creativity in accomplishing their task. It showed a possibility that the participants would use any format of TE. The use of TE by a teacher only showed the salience of linguistic forms. However, the use of TE by the participants showed not only the salience of linguistic forms but also some aspects of meaning.

2. One-Week Delay Recall Test With Notice

The first test involved recall. As the participants used their preferred TE technique, they highlighted language items they needed to retain. Consequently, it was expected that the participants would be able to memorize the language items under the TE without difficulty and to also reproduce the memorized sentences without much conscious effort. The results are shown in Table 1.

Each participant memorized 20 sentences (or utterances). In terms of completed sentences, Participant B performed the best (90%), followed by A (80%). However, Participant C scored poorly (45%). Participants A and B used proven strategies to focus on relevant language items, while Participant C’s strategy was to pay attention to the content of the movie clip, which was why her score was low. However, strategies for textual enhancement (STE), such as “underline,” “story map,” and “coloring” did not seem to positively or negatively influence sentence memorization, even though “story map” was the most effective. Although Participant A’s scores were slightly lower than Participant B’s, the difference was not statistically significant. Instead, psychological intention seemed important when participants used STE. Participants A and B focused on language items, while Participant C focused on content. Therefore, it can be surmised that STE may be related to language matters if STE targets users’ concerns regarding linguistic items. In contrast, if STE targets their concerns on content, it may not be related to language. Table 1 shows that Participant C did not employ a proper STE, which resulted in her low score.

Missing clauses refer to serious errors impeding understanding of sentence meaning. In this context, Participants A and B had no missing clauses. In contrast, Participant C had four missing clauses or sentences, indicating that her poor result was because she did not use her STE in language. The study then checked for minor errors that did not hinder understanding of the content. Participants A and B had few errors, but Participant C, as expected made many minor errors. In summary, the type of STE is taken according to where it is used. Participants A and B used STE to notice linguistic items, while Participant C used it on content.

3. Two-Week Delay Recall Test Without Notice

This test was the same as the first one, but the participants did not know that the test would be taken again. They were simply asked to recall the sentences they remembered the week before. The test aimed to see how many utterances they would remember and to determine how long the effect of their STE would last after one week. If the sentences stayed in the participants’ long-term memory, it would indicate the usefulness of STE in language learning and development.

In Table 2, Participant A’s number of perfect score sentences decreased from 16 to 9 sentences. Participant B could only recall 13 sentences, compared with 18 sentences in the previous test (see Table 1), but her score was still the best of the three. Participant C’s result was interesting in that she recalled the same number of sentences as the original test. Table 1 showed that Participant C came last in the first test, but in this test, she remembered the same number of sentences. Considering she had a weak point in language, this result was strange. How can this phenomenon be interpreted? The answer may be to do with meaning or content. Keep in mind that her STE focused on content. We can find the reason for this in cognitive grammar. According to Langacker (1987), the basic unit of grammar is a form-meaning pairing. The symbolic unit of language consists of a phonological and semantic pole. The phonological pole is a subdomain of the semantic pole. Meaning is primary, and form (including phonological structure) is secondary (Combs, 2008; Long, 1991). Thus, language users look for the relevant forms with meaning. This means that if Participant C intensively focused on meaning, the relevant language forms would hold well for a long time.

The comparison between Participants A and C is noteworthy—their scores reversed within one week. Both participants had a similar recall for missing clauses. Table 1 shows that Participant A had no errors in the clause missing category. However, Table 2 shows that he made five errors in clause missing in the second test. He also made the most minor errors. By contrast, Participant C made only seven minor errors (see Table 2), whereas she had made 16 minor errors previously (see Table 1). Although one week had passed and she did not review the 20 sentences, her result had unexpectedly reversed.

We can conclude, therefore, that meaning-based STE (Participant C) and form-based STE (Participant A) show a hypothetical rule: the recall ability of meaning-based STE stays stable with time, at least in this test. However, Participant B used a combination of meaning-based plus form-based STE, which might be why she had the best score.

4. Four-Week Delay Recall Test Without Notice

This third test was conducted without notice four weeks later. Again, the test aimed to determine which STE would be better with time. Common sense might tell us that four weeks is enough time for memorized sentences to be forgotten. Detailed results are shown in Table 3.

In Table 3, the second column, “full sentence,” indicates how many sentences the participants still remembered after four weeks had elapsed. Participant A remembered 16 sentences one week later, but with advance notice of the test, 9 sentences two weeks later (without notice), and 7 sentences four weeks later (without notice). This descent seems unsurprising because human beings tend to forget things as time passes. By contrast, Participant B moved from 18 → 13 → 17. Her recall went down, then up again. In the two-week delay test, she remembered 13 correct sentences, but her score improved in the four-week delay test, with 17 correct sentences. How could it be possible? How can four weeks later be better than two weeks later? It is possible that Participant B unconsciously reviewed her errors before she knew about the third test, but there is no way of knowing for certain.

Participant C remembered from 9 → 9 → 2 sentences. Table 2 indicates that Participant C’s score was not too bad because her meaning-based STE allowed her to recall a few sentences. However, Table 3 shows that Participant C’s memory clearly failed. It is likely that her memory based on meaning did not work four weeks later. Specifically, her symbolic unit—meaning-form pair—did not function four weeks later.

The third column in Table 3, “sentence order,” shows how the use of the participants’ STE represents memorization and recall. Table 3’s third column is detailed in Table 4.

Sentence order in Table 4 refers to the order of the sentences that appeared in the storyline of the movie clip. Participant A recalled 16 of the 20 sentences, but could not remember the storyline. Since his STE mainly focused on language, his story order was somewhat confusing. Participant B had an excellent recall, remembering 19 out of 20 sentences. Even after four weeks had passed, her recall was largely intact. Her STE might have focused on content and language, meaning that she paid equal attention to both content and language, which could be why she was able to recall most of the sentences.

Participant C recalled 15 sentences of the 20 sentences. The first column, “full sentence,” in Table 3, shows that Participant C could not remember the story sentences well, only being able to recall 2 sentences. However, this was about forms, not meanings. Table 4 shows that she managed to recall the meaning of 15 sentences, although it did not necessarily mean that she successfully recalled full sentences. It simply meant that she remembered the storyline in order, not the linguistic sentences.

Even here, Participants A and C were remarkably contrasting in their results. Participant A focused primarily on language, while Participant C focused on content. As mentioned already, Participant A failed to remember the storyline, while Participant C failed to remember the linguistic items. In this regard, STE functioned well for the respective participants: Participant A focused on language and got good results, and Participant C paid attention to meaning and also scored highly. Considering this data, instructors would recommend Participant B in an EFL classroom because she balanced language and content, successfully recalling 85% of linguistic sentences and having a near-perfect recall of the storyline (19 out of 20 sentences).

The completion rate in Table 5 refers to the amount of memorized language items against a whole sentence. For example, 1(53%) means that Participant A correctly identified 53% of the language items in the first sentence and successfully remembered 61% of the language items four weeks later. His STE would support remembering linguistic items as many as possible. Participant B recalled 91% of language items (mean), and Participant C remembered 43% (mean).

Table 5 shows that the STEs served their respective purposes despite each participant achieving different results. For example, Participant A used a language focus as his STE, and his average recall was approximately 61%. However, since he focused only on language, he could not successfully recall meaning-related language items. In contrast, Participant C focused solely on meaning, and could not successfully recall form-related language items. However, she did manage to remember the storyline and some relevant language items. Participant B achieved the best results because she could simultaneously recall both form and content.

In summary, the participants applied STE effects effectively to accomplish their goals. However, L2 learners should use STE for better language learning, focusing on form and meaning. Likewise, EFL teachers should remember that language consists of both form and meaning and should devote equal time to both.

V. CONCLUSION

One of the biggest tasks of movie English is how to deal with actual utterances and commit them to long-term memory. Considering class time is not long enough, teachers and students should work together and pay attention to target forms, including meaning. This study suggests that TE is the best way to achieve this; it is a good strategy for improving salience. However, TE is not the whole answer. It does not matter whether one student uses the bold format and another student uses the underline format, for example; what is important is how the student uses TE.

The three participants in this case study focused on different STEs in the recall: language (Participant A), language and content (Participant B), and meaning and content (Participant C). Over the three recall periods, Participant A tended to ignore meaning even though they were more successful in remembering linguistic items. With time, linguistic items tended to be forgotten. As mentioned, Tode (2007) experimented with the durability of linguistic items of explicit instruction and achieved similar results to those of Participant A. His recall also became weaker as time went by. Participant A’s data should remind reiterate the importance of meaning to EFL teachers and students.

Participant C, however, focused on the storyline and managed to successfully remember meaning-related utterances, scoring higher than Participant A in the second test. This seems to indicate that meaning memory may be easier than language memory because encyclopedic information, including language, retains its meaning (Corballis, 2019). However, Participant C failed to remember linguistic items in the third test. Although she scored well on the second test, she showed similar responses to Participant A. However, after four weeks, she had largely forgotten the linguistic items, remembering only 2 full sentences. Considering that she remembered 9 full sentences in the second test, we can only infer that her TE strategy did not work.

On the other hand, Participant B’s results supported this study’s objectives. She focused on meaning and form, and her TE was a story map. She paired form and meaning successfully, which possibly led to her successful memorization and recalling. We cannot be certain from the data which factors were responsible for Participant B’s high scores. It might have been the story map or some other strategy. However, it can be guessed that Participant B is an agent of using a story map. Then we can say that her strategy is more powerful than a story map per se.

There is a pedagogical implication in this study for EFL teachers. Language learning is concerned with pairing form and meaning simultaneously. Students often ignore the connection between the two because they think that they already know the meaning. Since the meaning is established from L1, students tend to ignore the meaning. On the other hand, form comes from L2, which might lead mislead students into paying too much attention to form but not enough attention to the connection between form and meaning. Therefore, EFL teachers should assist L2 students with finding a connection between form and meaning for better language learning.

The limitations of the present study include the limited sample size and the limited number of movies used as teaching material. Also, to conduct more in-depth studies, researchers should collect and analyze interview data from participants regarding form-meaning pairing.

Notes

In alphabetical order, Applied Linguistics, Canadian Modern Language Review, International Journal of Applied Linguistics, International Review of Applied Linguistics, Language and Education, Language Learning, The Modern Language Journal, Second Language Research, Studies in Second Language Acquisition and TESOL Quarterly.

The numbers indicate the order of the sentences and are identical to the numbers in the script given in the Appendix.