Translanguaging in Action: A Case Study on Two Korean Students’ Engagement in Translanguaging in Radio-Based English Education

Article information

Abstract

This case study investigates the engagement of two Korean college students majoring in English education with translanguaging. In a course that integrates the teaching of translanguaging and encourages active student participation in exploring translingual practices in everyday literacy, the study examined two students’ analysis reports on translanguaging in an EBS radio English education program, their reflection notes on translanguaging, interviews, and in-class discussions on the pedagogical potential of translanguaging. Two research questions were asked: How do Korean students majoring in English education apply translanguaging knowledge in analyzing an EBS radio English show, and what are their attitudes towards translanguaging? Utilizing a qualitative research approach, the study analyzed written and spoken data of the participants. The findings illustrated that the participants comprehended the crux of translanguaging and effectively applied it in analyzing the EBS radio program. They also employed their linguistic knowledge gained from other language education and linguistics courses to make sense of the translingual nature evident in the EBS teachers’ teaching practices. Moreover, they displayed a positive attitude toward translanguaging for English education in Korea, despite encountering challenges and ineffective translanguaging moments. This study calls for further research to advance the promotion of translanguaging in Korean ELT.

I. INTRODUCTION

In an increasingly globalized world, the dynamics of language use and interactions among various linguistic and cultural repertoires have inevitably situated us in a position where there is a need to move away from a monolingualism-oriented mindset toward translingualism to embrace a more extensive range of sociocultural and linguistic repertoires. Translingualism refers to a paradigm that understands language primarily as social practice (i.e., translanguaging), being interested in the meaning negotiation of multilingual speakers who actively participate in interaction drawing upon their full linguistic and cultural repertoires (Canagarajah, 2013). The perspective of translanguaging as a practical theory of language (Li, 2018) provides educators, teaching practitioners, and literacy researchers with a lens through which to explore the complexities of everyday language use, as well as language learning and teaching in diverse settings (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022; García & Li, 2014). In literacy education, including English as a second/foreign language (ESL/EFL), translanguaging offers learners the ability to navigate and utilize multiple languages fluidly, fostering an inclusive educational space that honors linguistic diversity and appreciates creative language use that may deviate from dominant language ideology (García & Kleyn, 2016; García & Li, 2014). In the tradition of translanguaging, language learning does not compel learners to do code-switching from their first language (e.g., Korean) to their second or foreign language (e.g., English) in which learners’ first language is often seen as a cause of negative transfer impeding mastery in acquiring the target language (see Sampson, 2011). Instead of viewing languages as objects accumulated through linguistic systems and sorted according to geopolitical distinctions (Saraceni, 2015), translanguaging promotes the utilization of linguistic and cultural resources as one full repertoire (Li & García, 2022) which allows code-meshing of language learners (Lee, 2014)—“the possibility that English and local languages may be combined in idiosyncratic ways as befit the speaker, context, and purpose” (Canagarajah, 2011a, p. 275). However, much of the research has been concentrated in Western contexts (Renandya & Chang, 2022), leaving a noticeable gap in the literature concerning ESL and EFL settings in Asia, including Korea, which is an underexplored discourse (Im, 2020; Rabbidge, 2019). Moreover, although research on Korean speakers’ use of translanguaging has usually focused on everyday literacy practices at home (Lee et al., 2021; Song, 2016), online discourse (Im et al., 2022; Kim, 2018), and pop culture (Ahn & Kiaer, 2021; Kiaer, 2018), the pedagogical context remains understudied. Translanguaging is suggested to be explicitly taught so that students can develop knowledge and proficiency by engaging in the analysis of translanguaging in use (Canagarajah, 2011b).

This case study on two Korean college students aims to contribute to filling this gap by investigating how Korean college students majoring in English education view and use translanguaging in their English learning practices. Specifically, the study focuses specifically on their engagement with an Educational Broadcasting System (EBS) radio program called Power English, a popular radio-based English teaching program in Korea. While technology and multimedia have rapidly evolved in the field of English language teaching (ELT), EBS is still regarded as crucial in providing high-quality educational content for free or at an affordable price to English learners of all levels in Korea. Yi (2019) highlighted that research on EBS English education has mostly been done in primary and high school settings, and there needs to be more focus on how to make the best use of EBS content. In this regard, building on prior studies that have mostly focused on classroom interactions (Creese & Blackledge, 2010; Paulsrud et al., 2017), this research expands the discussion by examining how translanguaging happens on this radio platform from the Korean college students’ perspectives. In other words, this study is significant because it looks at how Korean students majoring in English education use their translanguaging skills in a setting outside the traditional classroom, challenging conventional views on language learning. By exploring Korean English education major students’ active involvement with this popular educational resource through a translingual lens, the current study offers valuable insights that will be useful for both theory and teaching practices related to translanguaging, especially in East Asia. It also addresses the dominant ideology that often sees local languages as a barrier to EFL learning.

The research questions for the current study are as follows:

1. How do Korean students apply translanguaging to the analysis of the EBS radio English education program?

2. What are their attitudes towards translanguaging?

In the following sections, the concept of translanguaging will be discussed, along with a review of its utilization in the field of English education in East Asian settings. This will be followed by a description of the research context and the methods of data collection and data analysis. Following the methodology section, findings will be discussed in two parts: students’ ways of applying translanguaging knowledge to the radio English education program and their attitudes towards translanguaging. Pointing out several limitations of the study, it ends with implications for further research.

II. TRANSLANGUAGING AND REVIEW OF RELATED STUDIES

Translanguaging is best understood as both a paradigm and an approach to language(s) and languaging. Its focus lies in the dynamic use of all available resources for encoding and decoding language, participating in interactions, and expressing identities (Canagarajah, 2013). As a practical theory of language, translanguaging illustrates the natural practices of multilingual speakers who alternate and shuttle between and draw upon various linguistic and cultural repertoires (Li, 2018). This perspective provides a lens through which to view language use and its sociocultural consequences as well as implications for language education. It urges a move away from monolingual and homogeneous language ideologies, such as the “English fever” of Korea (Park, 2009). By emphasizing that our literacy practices are complex and situated within negotiations of meaning, translanguaging recognizes the rich diversity and fluidity of languages and how they intersect and interact. This approach not only contributes to a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of language practices but also has vital implications for pedagogical approaches (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022). Specifically, it disrupts traditional methodologies in EFL settings.

Research on translanguaging in the EFL educational context has shed light on its potential benefits for both learners and teachers (Liu et al., 2020; Zein, 2022). For instance, Rabbidge (2019) explored the effects of translanguaging in Korean EFL classrooms, demonstrating that a teacher’s use of translanguaging can foster a more inclusive learning environment. His research indicated that translanguaging enables less proficient English learners to articulate their thoughts using their native language (L1), leading to increased participation and reduced boredom. Likewise, Wang and Shen (2023) highlighted the effectiveness of purposeful pedagogical translanguaging in English-medium classes, where students expressed positive attitudes toward its use for explaining concepts, monitoring engagement, managing the classroom, and developing intercultural competence. This favorable outlook on translanguaging was further supported by Ahn et al. (2020). Their study revealed that leveraging a teacher’s full linguistic repertoire facilitated dynamic interactions among non-native English speakers and disrupted the native versus non-native speaker dichotomy. This shift in perspective was notably possible when Korean English learners saw themselves not as deficient but as competent additive language users who can draw upon their diverse linguistic resources. Complementing in-class observations, Im (2020) also advocated for local Korean English teachers to incorporate media resources in teaching translanguaging. The study suggested that by applying translingual strategies for negotiating meaning—which include understanding the use of language, body language, and cultural cues—Korean learners could critically engage with media. This engagement allows them to grasp how the boundaries between languages blur, making language a flexible, fluid, and socially constructed tool that connects individuals from different L1 backgrounds.

Recently, the academic discourse on incorporating translanguaging into language education has extended beyond traditional classroom settings. Yi and Jang (2020) examined the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a significant reliance on online instruction. Through their analysis of English teachers’ online lessons, they highlighted the strategic employment of translanguaging such as transliteration of converting English vocabulary into Korean to represent the sound of the original language and code-switching between Korean and English to maintain the nuances of the Korean words. These approaches were found to enhance students’ engagement and enjoyment, particularly due to the language disparities between Korean and English (Leonard & Nowacek, 2016). Additionally, the linguistic landscape of schools—encompassing language, imagery, and other semiotic elements—offers a rich context for understanding the operation of translanguaging. Gorter and Cenoz (2015) illustrated the incorporation of diverse multilingual signage and images, arguing that meaning emerges not just from individual languages or symbols but from the intricate interactions and interplay among these various elements. In a similar vein, Im’s (2023) research on linguistic landscape of a school setting examined language and image choices within a university setting, revealing that the institution’s physical environment can serve as a translanguaging space (Li, 2018). In such contexts, diverse linguistic and cultural resources are blended together to convey local identities and generate new meanings that invite more nuanced interpretation of meanings by local people.

As shown in the literature, translanguaging is increasingly seen as an alternative approach in the field of language education including ESL and EFL both locally and globally (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022; Li & Lin, 2019; Rabbidge, 2019; Zein, 2022). This approach wants to understand how all available linguistic and cultural resources are strategically employed and how meaning is discursively constructed during interactions in which meaning negotiation inevitably occurs. Although some studies have raised concerns about the allowance and presence of less-preferred languages in language education (e.g., L1, accented English, etc.) especially in contexts that values so-called standard English (e.g., Al-Bataineh & Gallagher, 2021; Rabbidge, 2019; Wang & Shen, 2023), an increasing number of academic discussion acknowledges its potential as a pedagogical tool for challenging and disrupting the status quo of monolingual, ideology-based language education. Consequently, the emphasis should not be solely on understanding the individual components of language resources. Rather, for translingual speakers equipped with a translanguaging instinct (Li, 2018), the focus should be on comprehending how these elements are integrated and presented as a unified repertoire in complex interactions within translanguaging spaces (Li & García, 2022). In line with this perspective, the current study seeks to explore an interesting case where Korean student-teachers majoring in English education are given an educational opportunity to apply their translanguaging knowledge to an EBS radio English education program by analyzing it and to reflect on their experiences in using translanguaging, which led to the formation of attitudes towards translanguaging.

III. METHOD

1. Research Context

This study explored a course offered in the Department of English Education at a research-intensive university in Korea during the Spring semester of 2023. Spanning 16 weeks, the course aimed to cultivate English reading and listening skills within an EFL context. The class consisted of 20 students, comprising five males and 15 females, and featured translanguaging as a central theme. Although the students reported no prior explicit instruction on translanguaging (Canagarajah, 2013; Li, 2018) or translingual pedagogy (Cummins, 2019; García & Li, 2014), they noted that these concepts were integrated or mentioned in other major courses in their curriculum. For instance, one of the textbooks they used in other major courses was Teaching by Principle, 4th Edition (Brown & Lee, 2015) which includes a section in its eighth chapter addressing translingual practices, the role of English as an international lingua franca, and the pluralism of English varieties. Within this chapter, students were introduced to how translanguaging diverges from traditional conceptualizations of bi- or multilingualism, focusing on the complexity and diversity of speakers from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds engaged in meaning negotiation. Similarly, the textbook How Languages are Learned, 5th Edition (Lightbown & Spada, 2021) briefly discussed translanguaging in the context of multilingual speakers’ language usage. This text emphasized that multilingual speakers do not compartmentalize their languages but employ a unified linguistic repertoire for encoding and decoding messages, a perspective beneficial for second language learners constructing their L2 identities. Consequently, the students realized that they were not entirely unfamiliar with the concept of translanguaging; however, they had not previously delved into its intricacies nor had the opportunity to apply these concepts in their own educational materials.

To teach translanguaging to Korean learners of English who are prospective English teachers, the curriculum was designed to address their specific needs and meet local educational requirements. The course included lectures on translanguaging, practical assignments for its application, and reflective exercises to assess its relevance in the context of English education in Korea. Initially, students were prompted to reflect on their experiences in learning and teaching English, often converging on the observation that English language education in Korea is predominantly oriented towards high-stakes testing. This issue was examined through the lens of the concepts of language and languaging (Swain, 2006) where language and language learning are perceived as the mastery of linguistic elements and a social practice (Saraceni, 2015). Subsequent lectures explored key translanguaging principles, including translingual meaning-negotiation strategies such as evoking, recontextualization, interactional dynamics, and entextualization. These were illustrated using readings from Canagarajah (2013) while concepts like translanguaging space and translanguaging instinct (Li, 2018) were also addressed. Given that most teaching materials were in English and rarely incorporated examples involving Korean speakers, media sources that described the English use by Korean speakers were added as supplementary materials. This enabled students to understand the mutual engagement in meaning negotiation between Korean and English-speaking interlocutors, as well as the significance of seemingly erroneous utterances in recontextualizing interactions (e.g., Im, 2020). Other supplements included an interview with pop singer Chungha, which was also used to illustrate the complex identity and literacy practices of Korean-English bilinguals. Such examples shed light on the fluidity of identities of multilingual speakers, complicating traditional categorizations of first and second languages and suggesting the usefulness of LX user identity (Dewaele, 2018; Li & García, 2022). Moreover, the concept of translingual words—terms that transcend linguistic boundaries and exhibit hybridity in a globalized world—was discussed using K-pop-related phenomena like mukbang that students are familiar with as explored in readings by Ahn and Kiaer (2021) and Kiaer (2018). These discussions prompted critical engagement with the notions of linguistic ownership and global meaning-making through English globalization and glocalization. To enhance understanding, the lectures were supplemented with readable reading materials both written in English and Korean (e.g., Conteh, 2018; Shin et al., 2017), allowing the students to deepen their understanding of what translanguaging is and how it is realized in various literacy practices.

Among many instances from the observations from the class, a notable instance was the application and extension of knowledge on translanguaging in an assignment of analyzing an EBS radio show from the lens of translanguaging. In this assignment, two students named Ms. Oh and Ms. Shin (pseudonyms) analyzed translingual teaching practices shown in an EBS radio program Power English which is designed for advanced English learners. To address the research questions, this study describes how these two students engaged in the analysis of translanguaging practices displayed in the radio-based English educational program and the attitudes shown in their reflective contributions.

2. Data Collection and Analysis

In the course offered by the English Education Department at a university in Korea for juniors and seniors majoring and minoring in English education, data for this study were collected from two participants (Ms. Oh & Ms. Shin) who voluntarily chose to examine an EBS English education radio program. The specific EBS English Education radio show chosen for the translanguaging assignment was Power English which was a suitable learning resource and research site for the participants for two primary reasons. Firstly, Power English is designed for advanced-level English learners with the aim of improving English conversation skills and offering opportunities for practice (see https://home.ebs.co.kr/powere/main for details). Since the department where the two participants study requires a TOEFL score over 80 out of 120 as a requirement for graduation, all students in the department almost always have English proficiency to get the score and, thus, easy-level programs such as Start English or Easy English which target novice learners would prove insufficient for their educational needs. Secondly, the educational program is not only freely accessible but also available on various platforms, granting audiences the flexibility to access it at their convenience. Power English airs for 20 minutes every Monday to Saturday, and it can be freely accessed through their radio frequency and website in real time. Furthermore, several paid platforms such as Melon also offer its content. This English teaching show is hosted by two teachers: one male American and one female Korean-American teacher both of whom are bilingual in English and Korean and fluent in two languages and cultures. The show is predominantly conducted in English, with minimal usage of the Korean language in comparison to other EBS radio English education programs which primarily target lower-level English learners and are conducted mainly in Korean.

These two participants of the study decided to dedicate the entire month of May 2023 to listening to all episodes of that month. During the month, they self-researched an assignment to investigate the way the concept of translanguaging is realized in the EBS program. Their objective was to analyze how translanguaging was interwoven into the radio show and how it was put into practice by the two teachers hosting the show. Consequently, their focus extended beyond the program’s content to include an examination of the diverse strategies employed by the host teachers. These educators effectively utilized their extensive linguistic and cultural repertoires to enhance their teaching methods. This EBS program served as a safe and conducive space for exploring the repertoires of translingual speakers, as described by Canagarajah (2011b). It presented an invaluable opportunity for the students to gain insight into an alternative teaching context, which is a fundamental aspect of a teacher’s professional development (Yook & Lee, 2016).

The data consists of four types. Firstly, the mentioned two participants submitted their own analysis reports of translanguaging as found in Power English. In addition to this analysis assignment, secondly, they were asked to submit reflection notes in which they expressed their thoughts and opinions on translanguaging, how it differed from traditional perspectives on language and languaging and education they had previously encountered, its potential application in Korean ELT, and other issues they wished to share. Thirdly, this written data was supplemented by oral data. They engaged in conferencing with the researcher after completing their own EBS radio show analysis. During these conferences, they were asked general questions about translanguaging and their attitudes towards it. Conversations were documented in real-time, both during and immediately following the individual interactions between the participants and the researcher.

A qualitative approach was employed to unpack the diverse responses of the aforementioned two participants, examining their reflections about their own English education experiences and assessing changes in their attitudes during and after engaging with translanguaging (Cresswell & Cresswell, 2017; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). The collected data were read multiple times by the researcher with a focus on identifying recurring themes across the datasets. In the analysis of the students’ reports, the analytic focus concentrated on the participants’ insights regarding translingual meaning negotiation strategies and pedagogical translanguaging practices. The accuracy of the participants’ understanding of translanguaging in the radio English pedagogy context was assessed by drawing upon previous research on translanguaging that provided categorical distinctions on various translingual strategies including Canagarajah (2013), Fang and Liu (2020), and Rabbidge (2019). These approaches were compared with oral data such as interviews and in-class interactions to understand how the students applied their knowledge and how their attitudes informed their works. The spoken data obtained from interviews and classroom discussions were analyzed through multiple listening to identify relevant moments which were then thematically coded in terms of their application and perceptions of translanguaging. These analytical findings were subsequently triangulated to ensure that the researcher’s data analysis effectively reflected the voices of the participating students.

IV. RESULT

The analysis of the data reveals that the participants of the study were able to effectively apply the knowledge on translanguaging they learned from the classes to their analysis of the English education on the radio platform. They showed a keen interest in diverse aspects of translanguaging in this context, particularly focusing on its effective use by the EBS teachers. The findings illustrate that the teaching of translanguaging to Korean student teachers majoring in English education appears to be effective in that it led to a transformative impact on their perspectives in ELT.

1) Application of Knowledge on (Trans)languaging

(1) Translingual Meaning Negotiation Strategies

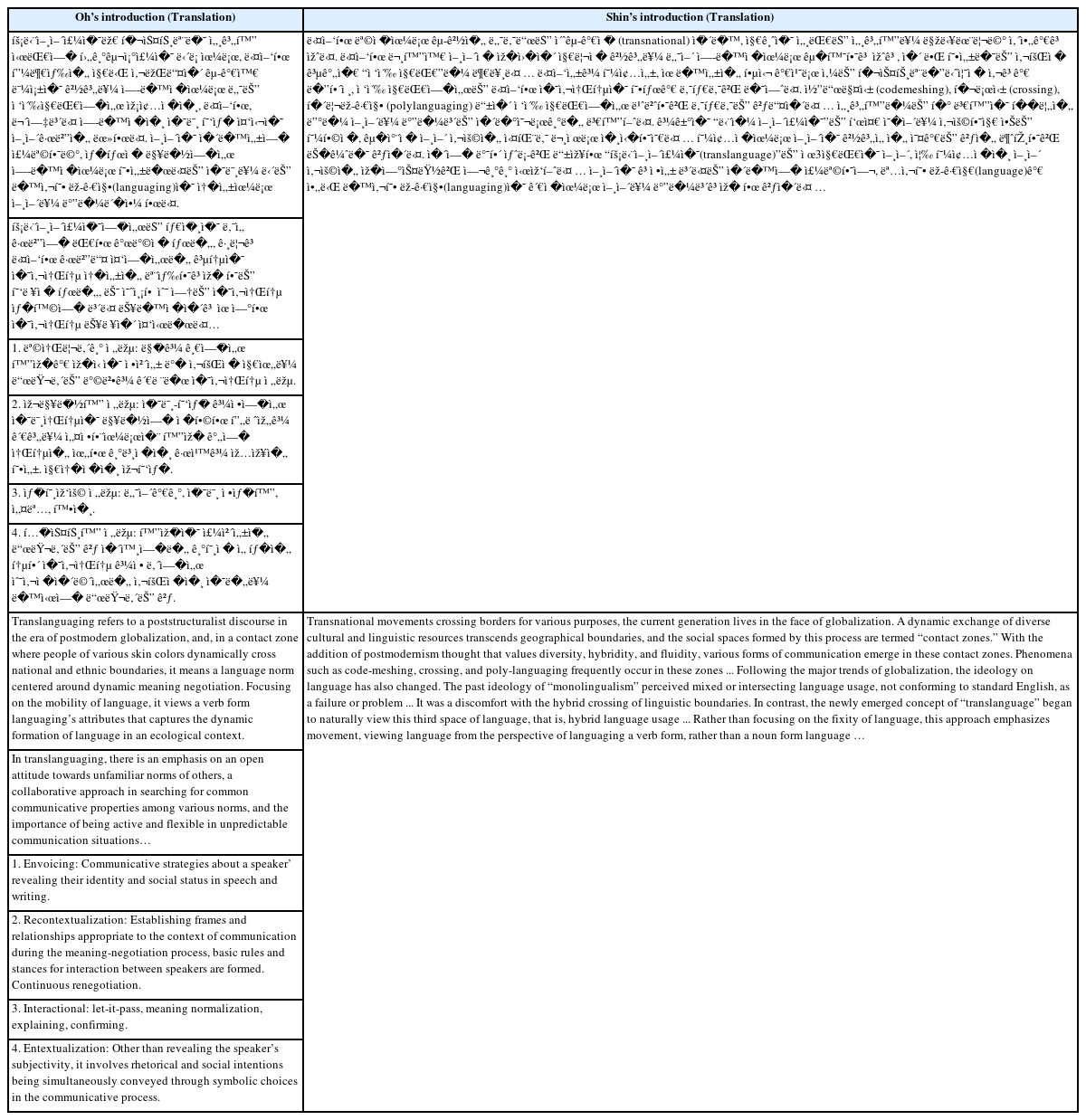

The analysis revealed that the participants successfully interpreted the mechanisms of translanguaging from the EBS English education program by categorizing various meaning negotiation strategies and labelling translanguaging pedagogical strategies. Their main focus lies in the identification of code-switching, code-meshing, and other strategies commonly used in spoken discourse. As seen in Table 1, the two participants approached their assignment of analyzing Power English through the lens of translanguaging space (Li, 2018) which is a conceptual framework that allowed them not only to apply existing knowledge but also to cultivate a translanguaging instinct. This instinct enabled individuals to fully utilize their linguistic repertoire (Li, 2018). This evolving sense of a translingual speaker identity was evidenced by their use of academic terms such as “languaging” and the Korean translations of Canagarajah’s (2013) strategies for translingual meaning negotiation as seen in Oh’s report. Further evidence includes references to “transnational movement,” “crossing,” and “poly-languaging” written in Shin’s report.

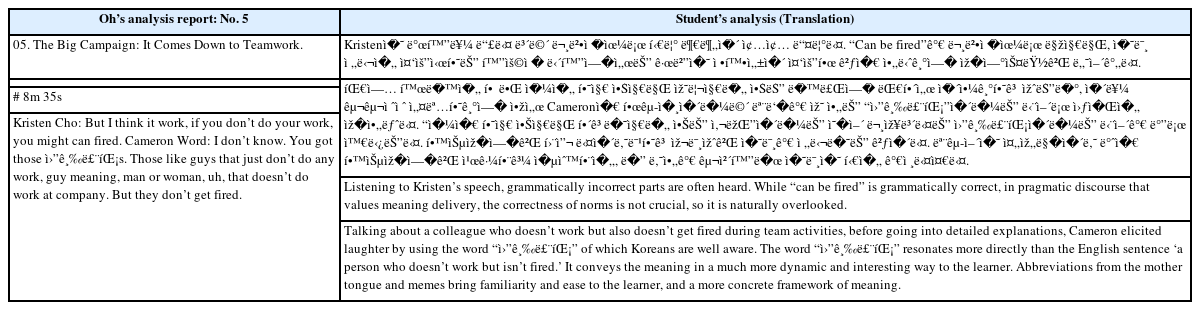

The reports also contained the detailed ways the participants situated EBS teachers’ various teaching techniques at the translanguaging space (Li, 2018) in which teachers’ mundane teaching practices were regarded as the pedagogically meaningful translanguaging moments. For example, the participants used their knowledge about translanguaging to make sense of the use of a Korean content word and the Korean-English code-meshed sentences frequently shown during the EBS education show that is arguably run entirely in English by native English speaking teachers. As illustrated in Table 2 and Table 3 below, the participants identified the employment of the term “월급루팡” that portrays a recent social phenomenon in business where individuals are not fully committed to work. In discussing the EBS teachers’ translingual ways of explaining employees who make minimal effort but would not be fired, the participants posited that directly inserting the Korean term would enhance the Korean audience’s intuitive understanding of the concept in comparison to the English-only explanation. They argued that translating or rephrasing the term into an English counterpart could compromise its original, socially accepted meaning made in Korea (Ahn et al., 2020). Consequently, adhering to a shared linguistic element (i.e., the term used in Korean) proves to be more effective from a translingual pedagogical perspective when dealing with terms that resist straightforward translation (Darvin & Zhang, 2023).

This analysis of translanguaging was centered on its function, which, as seen in Table 3, led to a participant’s awareness raining about the efficacy of specific practices in given moments. By mentioning the teacher’s translanguaging was more appealing, she stated that this teaching practice can deliver meaning more directly, which is the function of code-switching that elicits “socializing” to “ensure the message has been understood by everyone” and to “develop a sense of group solidarity” (Sampson, 2011, p. 7).

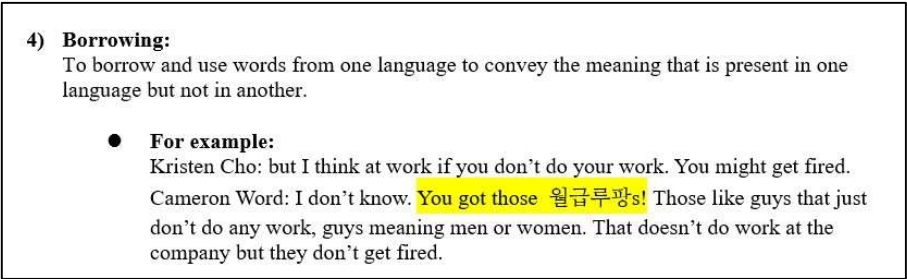

This analysis was later re-named as a “borrowing” translanguaging strategy by the participant Shin (see Figure 1). After understanding the phenomenon of putting the Korean keywords while speaking in English, she utilized insights gained from other classes to categorize this strategy employed by the two EBS teachers according to functions. This example demonstrates that those who learn translanguaging can actively extend their knowledge by devising new categories of translanguaging strategies that are more contextually relevant to their experiences and thus can fit better into their own context.

(2) Application and Expansion of Sociolinguistics and Language Education-Related Knowledge

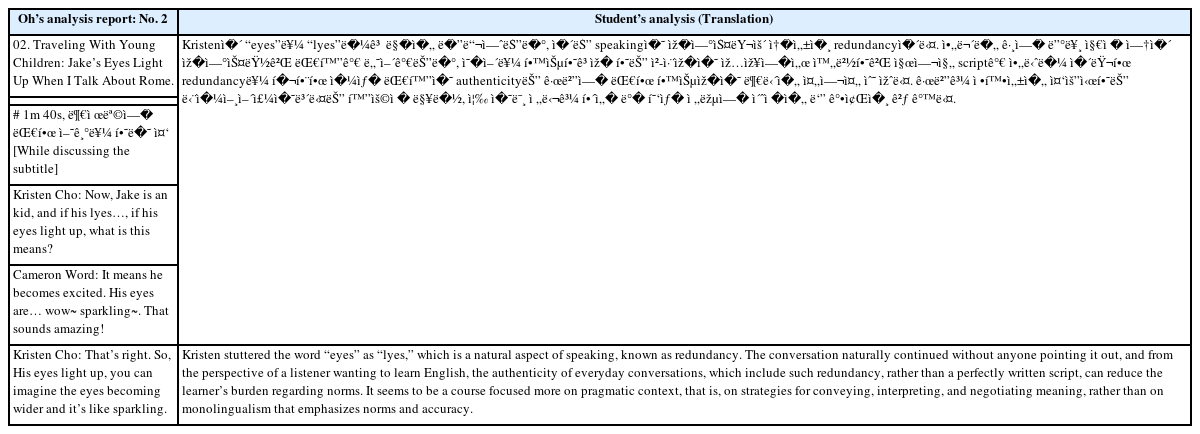

Another important finding is that the participants drew upon a diverse range of knowledge acquired from other courses to make visible the translingual nature of the EBS radio program. In engaging with EBS content, they adopted both metacognitive and metalinguistic approaches, which facilitated their understanding of how natural spoken language takes place translingually and how the use of two different languages can synergistically aid in understanding grammar (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022; Vaish, 2019). The following example is from Oh’s analysis report (see Table 4). While listening to an episode, she identified several errors made by the female English teacher, Kristen Cho, and these errors were neither corrected by the other teacher nor did they disrupt the overall flow of the interaction between the two educators. The participant Oh did not express any disappointment about the English speaker’s mistake; instead, it was regarded as what to happen naturally in real communication.

Oh’s tolerance towards the EBS teacher’s errors, which was also observed in Table 3, seemed to come from her application of the concept of “redundancy” in spoken discourse, a notion she had previously learned. According to the textbook Teaching by Principles by Brown and Lee (2015), redundancy in spoken language is described as a naturally occurring feature that “helps the hearer to process meaning by offering more time and extra information” and that “learners can train themselves to benefit from such redundancy by first becoming aware that not every new sentence or phrase will necessarily contain new information and by looking for the signals of redundancy” (p. 323). Oh’s case illustrates that by leveraging her prior knowledge in sociolinguistics and language education, she was able to see the objectives of the English education program regardless of unimportant language errors and mistakes that had nothing to do with the core lesson goals of the program. The EBS program was characterized by her as “a course focused more on pragmatic context, that is, on strategies for conveying, interpreting, and negotiating meaning, rather than on monolingualism that emphasizes norms and accuracy” as written in her notes (see Table 4). This orientation aligns with the core principles of translanguaging.

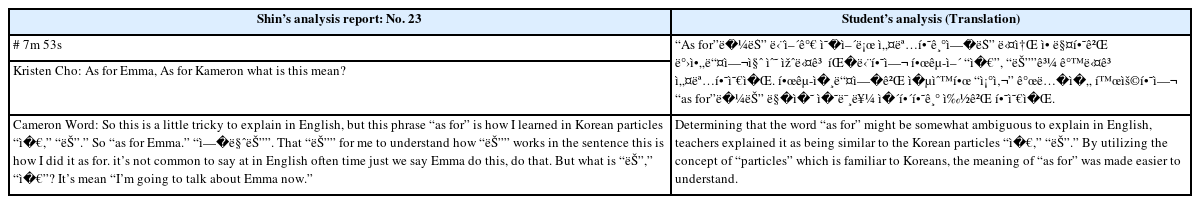

Another example involves Shin’s analysis of the employment of the learner’s L1 in the explanation of English grammar. As illustrated in Table 5 below, she observed that the English-speaking teacher’s use of the Korean topic marker (은/는), while explaining an English phrase “as for,” facilitated a better understanding for Korean audiences. This was in contrast to an approach that depended only on English explanations. This comparative analysis between the two languages was made possible by the teacher’s language comparison analysis and her metalinguistic knowledge, making her perceive the gaps and distance between the two languages as an opportunity to do the oneto-one matching grammar understanding. Specifically, she was able to understand how a grammatical element in one language corresponded to a different expression in another language (Cenoz & Gorter, 2022), which did not require a language to be used extensively in order to explain a phrase in that language.

The examples provided by the participants indicate that the students became more interested in the pedagogical functions of translanguaging strategies while listening to the educational radio show. Their analysis reports highlighted a shift in focus from merely listening to the EBS program for the purpose of understanding and interpreting the English language and target expressions to seeking to explore how the EBS English teachers delivered their messages in a translingual manner with the translingual strategies. This shift helped them to view language and languaging more as a social practice (Saraceni, 2015). They recognized that grammatical accuracy is not always guaranteed simply because speakers are native English speakers, but more crucially, the mutual efforts of interlocutors to engage in conversation play a more important role in determining successful interaction (Im, 2020). Additionally, they found that explanations solely in English were not always helpful for understanding English grammar; instead, the strategic use of the learner audience’s language (i.e., Korean) can facilitate learning.

2) Attitudes Towards Translanguaging

(1) Positive Stance Towards English Varieties and Code-Meshing

The students commonly observed that learning translanguaging as one of the main course goals and the EBS radio analysis project led them to realize that, although the radio program claimed to be conducted entirely in English, there were numerous instances where Korean was utilized as a source of teaching. They pointed out that various translanguaging moments including tactical use of the Korean language differed from their notion of an ideal, English-only class in which language learners experience immersive language learning. Moreover, they felt that these instances more accurately and realistically reflected the reality of classrooms in Korea that they will eventually be located in the near future when they become English teachers.

We [students majoring in English Education] were told that our national curriculum promotes Teaching English in English and Communicative Language Teaching. That’s why we always work hard to prepare for microteaching sessions that are needed to be conducted entirely in English. But, as evidenced by this EBS radio show, the notion of English-only teaching looks somewhat illusory, given that both the teachers and the students are Korean speaking Korean as L1. I now have reservations about whether the complete exclusion of the Korean language would actually be beneficial. (Shin, interview)

As much previous research has pointed out, a policy of using the target language only has been shown to be less effective (Li, 1998), particularly for less proficient local English teachers who feel incompetent and guilty for using their first language because they are not able to conduct classes entirely in the target language (Rabbidge, 2019). Similarly, efforts to create an English-only learning environment in non-English speaking countries, exemplified by the artificial construction of English-speaking kingdoms called English Village have also proven unsuccessful as evidenced by the declining business of English villages in Korea (Hong, 2016). What these situations have in common is that the Korean language, despite its status as a shared linguistic repertoire among members of the same society, is treated as something to be removed from the English learning process. But, from the perspective of translanguaging, the Korean language is a resource on which both learners and teachers can strategically count. Utilizing it effectively and efficiently with the aim of translanguaging can maximize student engagement and active participation, informed by a careful consideration of learners’ language backgrounds (Itoi & Mizukura, 2023), and contribute to creating an inclusive learning environment (Rabbidge, 2019). This inclusive approach to translanguaging, facilitated by the use of the Korean language, was noted by Oh, who both realized and experienced the effects of translanguaging.

When I realized that there was in fact a lot more Korean used than I initially expected, I felt relieved because it became easier for me to understand the content and thought that this program was made for me like Korean English learners. (Oh, interview)

The strategic insertion of Korean vocabulary or four-character idioms was seen as an intentional use of a shared language by English speaking teachers of the EBS. This intentional inclusion of Korean elements helped Korean audiences to more effectively achieve the program’s objectives while leading them to spend less attention to less relevant, difficult portions of the content. Furthermore, this positive attitude towards incorporating the learners’ first language expanded the Korean learners’ considerations of employing translanguaging in other discourses. For example, Oh expressed a radical idea on translanguaging; she suggested that she probably attempts to use translanguaging strategies in the TOEFL speaking and writing sections. She said:

I probably consider doing what I observed from this [translanguaging shown in EBS radio English show]. The exam is to assess how proficient an English language learner is, not to evaluate how much American we are. So, I guess it could be okay and acceptable to behave normally as we use English in Korea in our own way. (Oh, interview)

In conclusion, the participants’ firsthand experience with translanguaging in their own learning environment expanded their understanding of the multilingual and multicultural dynamics of interaction in an English education discourse. Consequently, the use of the participants’ first language came to be viewed not as an obstacle to English acquisition but as a valuable asset in translanguaging practices. This shift shows the development of a positive non-native speaker identity (Ahn et al., 2020) and the formation of an idealized, positive imaged identity of bilingual educators. (Rabbidge, 2019)

(2) Ineffective Translanguaging Moments

Translanguaging English education on the radio did not always elicit positive feedback from participants. Two cases that can be regarded as exclusive translanguaging teaching practices (Rabbidge, 2019) did not fully facilitate learners’ engagement. One moment they felt not engaging was when they found themselves confused about the host teachers’ humor that was culturally bound. For example, one participant mentioned that she did not understand some of the English teachers’ humorous jokes and joyful conversations, which left her confused and unable to tell when to laugh. They revealed that since humor was culturally bound and was also highly personal, sometimes humorous moments were not intuitively appealing to them, which also made them doubt the effectiveness of humor in language education. In addition to language barriers, which can marginalize students’ engagement (Itoi & Mizukura, 2023), cultural distance can also make learners feel less engaged.

Another case was from the moment of their realization that they depended too much on the Korean linguistic cues, which is also partially seen as one of the translanguaging natures of the teachers in the show. In other words, the EBS English teachers are proficient in both Korean and English and well-versed in the corresponding cultures, facilitating their ability to shuttle between languages and cultures and navigate the subtleties of the two discourses (Canagarajah, 2013). Thus, these bilingual teachers often code-meshed languages and moved from the target language-only explanation to the shared language explanation by repeating the important parts of the lesson. This practice unexpectedly and unintentionally led Korean learners of English to disengage during the first explanation of the content material because the learners anticipated that crucial content information would be going to be repeated in the shared language (i.e., Korean) later. An interview with Shin elaborated on this aspect:

Korean explanations occurred a lot more frequently than I had anticipated. Because of this, I sometimes didn’t feel the need to pay full attention to the initial explanation [of the key expressions of the episode]. I could simply match the English key expressions with their Korean counterparts at the end of the episode. The English teachers on the EBS Power English almost always provide Korean vocabulary during the review segment at the end. (Shin, interview)

Since understanding some concepts in the target language (i.e., English) is not always easy and intuitive, the participants revealed that they sometimes deferred their understanding and waited with the expectation that any unclear part of the EBS teachers’ English explanation will be understood when repeated and clarified in the Korean language. This finding is in contrast with Wang and Shen’s (2023) case in which Chinese EFL learners viewed translanguaging to be useful for them to comprehend difficult concepts.

V. CONCLUSION

This study investigates how Korean pre-service teachers majoring in English Education would interpret the concept of translanguaging in a major course to become future English educators in Korea. The results of the qualitative data analysis indicate that the two participants described throughout the study successfully integrated their understanding of translanguaging into the analysis of their own English learning experiences. Moreover, these two students were able to draw upon sociolinguistic theories and concepts of second language acquisition to comprehend the translingual features of the EBS radio program and its teachers. Overall, the participants of the study showcased an increased interest in the pedagogical implications of translanguaging teaching practices and the role of translanguaging in this kind of radio-based educational content. In addition, they exhibited less concern for the linguistic precision of the instructors’ pedagogical methods. The study participants identified multiple instances where the English-speaking EBS teachers effectively implemented translanguaging strategies, extending beyond the conventional understanding of code-switching. In this context, the English teachers skillfully integrated their linguistic repertoire, leveraging the complexities of both languages to enhance instructional clarity and student engagement as well as to create inclusive, fun-and-easy learning environment (García & Li, 2014).

These findings suggest that assigning tasks that require the application of translanguaging theory serves as an essential pedagogical opportunity to broaden their knowledge and perspective on language education in the EFL context. It helps Korean student teachers specializing in English education to navigate the translanguaging space within which they can critically evaluate how translanguaging functions in the local educational discourse and integrate this understanding into a broader conceptual framework (i.e., translanguaging). This process ultimately fosters a transformative change in their beliefs in what it means to teach English today and impacts everyday literacy practices (Gorter & Arocena, 2020). It does so by offering them an opportunity to explore translingual practices in a radio English education program. In line with previous research on translanguaging by English teachers and in English classrooms in Korea (Ahn et al., 2020; Im, 2020; Rabbidge, 2019), the findings suggest that there is a need for spaces and practices where both Korean teachers and learners of English can become more aware of the existence and pedagogical potential of translanguaging within the context of ELT in Korea.

One of the critical factors that influenced the successful implementation of translanguaging for Korean learners of English is their proficiency in English and their abundant knowledge of linguistics and education (cf. Vaish, 2019). The participants demonstrated their ability to understand how translingual practices function and, more importantly, to utilize their understanding of translingual meaning negotiation strategies and sociolinguistics in their own English learning on the radio platform. As they analyzed the English-only EBS radio program, they were able to identify subtle errors, such as the omission of the be-verb in Korean-American host Kristen’s speech, as observed in Oh’s example. Since their high-level English proficiency enabled them to focus not only on the content of the EBS radio program but also on its linguistic aspects, they could engage in metacognitive reflection to understand what was happening in the teaching process and also to think critically about how knowledge is discursively constructed and conveyed through translanguaging practices. Furthermore, when analyzing the content, they also drew upon their understanding of sociolinguistic phenomena such as “borrowing” as seen in Shin’s example and the “redundancy” inherent in natural spoken language as observed in Oh’s example. This rich base of knowledge empowered them to appreciate the teaching practices in the EBS radio program from the pluralistic perspective, offering them a nuanced understanding of how languages and cultures are collaboratively situated and intertwined in educational settings.

While the participants displayed mixed attitudes toward translanguaging in their reflections, they were generally interested in the concept of translanguaging and found it useful as a new lens through which they understand both the content of English education and their own experiences as English learners and as future English teachers. Furthermore, the fact that these participants were not merely learners but also prospective English teachers in Korea appeared to influence their perception of the effectiveness of incorporating their first language into teaching (Macaro & Lee, 2013). In traditional teacher training curricula to train student-teachers in teaching skills and methodologies, little attention was paid to emerging theories and approaches like translanguaging. This omission partially led them to believe English education should be all about implementing a wide range of teaching skills and methods such as Total Physical Response (TPR) and Jigsaw, arguably restricted to the use of the target language. In addition, the relative absence of ideological pressures, such as the pressure to speak grammatically correct standard English in test-oriented contexts, enabled the participants to more openly engage with translanguaging practices (e.g., Al-Bataineh & Gallagher, 2021).

The limitations of this study should be interpreted as possibilities and needs for further research. First, the number of participants was relatively small although the depth and multi-layered data gathered to some extent compensated for this limitation. The duration of translanguaging instruction could also be seen to be insufficient for making meaningful changes among Korean learners of English especially given that translanguaging is typically explored in graduate-level seminar courses and its understanding requires a certain level of expertise in literacy research (e.g., Schreiber & Watson, 2018). Since translanguaging is considered an alternative to monolingualism-oriented approaches (Li & Lin, 2019; Liu et al., 2020), the study should have checked the prior knowledge and attitudes that participants had to different methodologies and theoretical frameworks in ESL/EFL learning and teaching.

Despite its limitations, the present study serves as a meaningful attempt to integrate translanguaging into (student)teacher education within the context of ELT in Korea. This was achieved not merely by delivering knowledge about translanguaging through classroom materials and lectures but also by situating students at conducting the assignments to see how translanguaging operates through their own learning experiences. As Canagarajah (2013) points out translanguaging as our mundane everyday literacy practices, the insights from this study can offer valuable guidance for scholars and practitioners keen on nurturing a translanguaging-oriented mindset. This study calls for further research on the subject of translanguaging within the Korean ELT context for which the voices and perspectives of students, teachers, faculty members, administrators, and parents should be investigated for better educational opportunity and advancement. The anticipated result of the robust discussion thus is to challenge dominant ideologies of native-speakerism and the test-oriented, linguistic accuracy-based approaches that currently pervade ELT (Li & Lin, 2019), positioning translanguaging not merely as a tool but as a transformative agent to disrupt these unhealthy norms and ultimately contribute to a more inclusive educational environment through translanguaging.