Design for a Literature and Film Course Using a Mixed (Learner and Teacher-Centered) Approach

Article information

Abstract

This study aims to mitigate the difficulties (e.g., lack of clarity, confusion, and resistance) of implementing a student-centered learning course in a traditionally teacher-centered context (Kim, 2015) by adding elements of direct instruction to the student-centered curriculum. In this mixed-method (student and teacher-centered) elective course, thirty Korean intermediate university EFL students from multiple disciplines chose the class materials–the novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Dahl & Schindelman, 1964) and its two film adaptations (Burton, 2005; Stuart, 1971). The participants then designed and implemented project-based activities as well as the means of assessment while the instructor facilitated the activities and delivered lectures and mini lessons based on students’ needs. To analyze student and teacher perceptions of the mixed-method approach as well as students’ description of their self-efficacy, the researcher applied a qualitative analysis of student and teacher journals as well as post-course interviews. The results showed that the mixed-method approach can lead to several benefits including authentic direct instruction and an improved sense of self-efficacy in teachers and students. One unexpected result was student satisfaction with the low-stakes atmosphere created by background music played during group activities. Some limitations such as teacher workload, assessment accuracy, and small sample size are described.

I. INTRODUCTION

Throughout history, the world of education has seen a variety of both teacher-centered and student-centered instruction methods employed in classrooms. In its most basic form, a teacher-centered approach to learning finds the teacher as the all-knowing figure in the classroom who imparts knowledge on the subjects (i.e., students). In other words, “teachers expect their students to receive rather than to construct learning, and classroom relationships are based on distance and formality with a high degree of teacher-centeredness” (Hird, 1995, p. 2). On the other hand, the student-centered method “requires learners to participate and negotiate actively in meaningful interaction in order to interpret and construct meaning by themselves” (Nonkukhetkhong, Baldauf, & Moni, 2019, p. 2).. Educators who favor the student-centered approach to learning argue that it encourages language spontaneity, trial, and error (i.e., a more real-world communication style). Building on the ideas of prominent scholars such as Dewey (1902), who first introduced the idea of a student-centered curriculum in his book, The Child and the Curriculum, and Freire, whose work beginning in the late 1960s presents “a student centered system of learning that challenges how knowledge is constructed in the formal education system and in society at large” (Rugut & Osman, 2013, p. 28), researchers continuously assert that learner-centeredness gives the students more power to control their own learning, thus empowering them in their day-to-day lives (Friere, 1993; Hall, 1999; Santi & Gorghiu, 2017).

If teachers decide to approach curricula with learner-centeredness in mind, though, they must also consider the context in which they are operating. According to Hird (1995), “teaching methodologies that dismiss the local context are unlikely to flourish” (p. 4). More specifically, Nonkukhetkhong et al. (2019) noted that in the global context, administrators continue to implement policies toward learner-centeredness in the classroom; however, due to lack of teacher training and learner readiness, implementation is failing on a local level. In Korea, the Ministry of Education has made efforts over the past two decades to adopt student-centered learning strategies in K-12 (Ministry of Education, 2015). Lee and Baird (2021) point out that the shift in policy “is a relatively new development, and steep learning curves have been reported for both students and faculty members” (p. 291). DeWaelsche (2015) summed up their interpretation of the situation by stating that “what the Ministry of Education calls for in theory rarely occurs in practice as teacher-dominated classrooms remain common in Korea” (p. 132).

The challenges behind the steep learning curve in Korea have been well-documented in the literature, one major narrative stating that an emphasis on rote learning for standardized exams coupled with Confucian ideals (e.g., reverence for authority figures) results in a tendency toward teacher-centered lessons and passive students who are uncomfortable when it comes to critical thinking or taking part in communicative activities that require sharing original thoughts and ideas (Choi & Rhee, 2013; Lee, Fraser, & Fisher, 2003; Lee & Sriraman, 2013; Park, 2015; Ramos, 2014). Such research suggests that after generations of studying in traditional classrooms, learners (and teachers) in Korea are more likely to suffer in unfamiliar classroom environments. Some recent evidence exists, however, that suggests students in Korea can gain a sense of self-efficacy when placed in a properly designed project-based (student-centered) learning environment (Choi, Lee, & Kim, 2019). This paper is not a critique of the Korean education system or of teacher-centered instruction. Rather, the aim of the current study is to add to the growing body of research that provides insight into how instructors in the Korean EFL context can implement student-centered instruction in a way that makes learners and instructors comfortable and confident in the classroom.

The following paper begins with a review of the literature regarding both teacher and student-centered classrooms as well as literature that discusses instances of mixed-method (student and teacher-centered) approaches. The paper then builds on the work of Kim (2015), who tried to implement a student-centered, project-based learning course in a Korean university EFL context but faced difficulties due to lack of clarity and lack of teacher-centeredness in the traditionally teacher-centered context. To mitigate the difficulties that Kim (2015) reports, the teacher in the present study implements judicious direct instruction between longer periods of project-based learning activities. The students in the current course chose to focus on a popular novel, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Dahl & Schindelman, 1964) as well as its two film adaptations Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (Stuart, 1971) and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Burton, 2005). Finally, the paper lays out teacher and student responses to the course as well as implications for future courses and studies.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Rationale for Using Films and a Novel in a Mixed-Method Course

There is no shortage of research that reports the effectiveness of using films and novels to teach English. In terms of novels, Tsai (2012) writes about motivation, saying that when someone picks up the right book, they can be swept away by the characters and the plot and thus gradually develop intrinsic motivation that makes them continue reading. Then when they finish the book, they feel a satisfying sense of accomplishment and become more inclined to pick up another book. In addition, extensive reading, and exposure to longer, interesting texts has been shown to solidify grammatical knowledge, improve vocabulary, and raise cultural awareness within learners (Pellicer-Sánchez & Schmitt, 2010).

As for teaching English through film, Blasco, Moreto, Blasco, Levites, and Janaudis (2015) assert that “using movies in teaching is an effective way to reach people’s affective domain, promote reflective attitudes, and link learning to experiences” (p. 2). The current course is centered around projects and discussions that prompt students to think about their own lives and cultures. Specifically, the aim of this course is to help students link their own experiences to the characters in a meaningful way that allows learning and growth to occur. Vincent (2016) points out that using novels and films can engage and inspire EFL students by “bringing human concerns dealt with in novels and films to the students through the language they are learning” (p. 68), and finally, Riding and Sadler-Smith (1997) point out that students have different learning styles, and that some students may be better equipped to comprehend a text more easily than a film adaptation or vice versa. Either way, the instructor’s intention is to provide the students with an ample amount of material that will allow them the richest experience possible.

2. Teacher-Centered Classrooms vs. Student-Centered Classrooms

In the traditional, teacher-centered (otherwise known as “active teaching” or “explicit instruction”) classroom, we can see a teacher at the front of a classroom full of wide-eyed learners who are diligently copying down in their notepads the information the teacher writes on the board. To transmit knowledge, the teacher makes points, demonstrates ideas, and corrects students’ errors. From time to time, students ask questions to the all-knowing teacher, who answers the question correctly before moving on to the next point (Schug, 2003; Thornbury, 2005).

Traditional methods have been criticized since they do not create a classroom environment that fosters critical thinking and problem-solving skills. As a result, policy makers and educators around the world have shifted from the traditional, teacher-centered classroom to more student-centeredness in classroom instruction. In the student-centered (a.k.a. learner-centered) approach, “it is recommended that teachers enhance intrinsic motivation of students in student-centered classrooms which benefits students to develop their autonomy and encourages them to make responsible choices” (Serin, 2018, p. 166). Ritchhart, Church, and Morrison (2011) explain that instead of focusing solely on content, teachers must think about how to “foster students’ engagement with ideas” (p. 2). In other words, teachers can help promote a deeper understanding of material by offering students core ideas with which to engage rather than presenting a set of ideas as truth without opportunity for further exploration. The teacher’s responsibility is to play the role of facilitator, creating “a symmetrical power relationship between teachers and students” (Kim, 2015, p. 78), and allowing students to collaborate while also providing guidance and scaffolding as necessary to help them achieve their (self-stated) learning goals (Holmes, 2004).

In terms of creating a learner-centered environment for English language learners specifically, a significant amount of research has been conducted. Researchers like Legutke and Thomas (1991) state that learner-centeredness is crucial to communication. Furthermore, using computer technology (Warschauer, 2004) combined with a second language as a real social tool (Dewey, 1938; Freire, 1993; Fried-Booth, 2002; Moursund, 2003) can empower learners to make real changes in their own lives as well as (perhaps) the societies in which they live.

3. Mixed-Method Classrooms

1) Student Perception of the Mixed-Method Classroom

According to some research, the most effective teaching strategy seems to lie somewhere in between teacher and learner-centered methodologies. For example, Lak, Soleimani, and Parvaneh (2017) found that in a reading class at an English institute in Iran, reading comprehension post-study scores were better both in a teacher-centered and in a student-centered classroom, but that scores improved to a greater degree after student-centered instruction. In the Indonesian EFL context, Emaliana (2017) observed that learners showed a mildly negative attitude to the teacher-centered approach; however, the students admitted that teacher and student-centered activities were both helpful and unhelpful at times. That is, not one or the other, but a combination of both teacher and learner-centered approaches suits learners in this context. Similarly, Burns and Goldie (2000) found that, overall, a modern, learner-centered approach led to learners’ improved self-confidence and perception of improved learning; however, learners did prefer elements of the traditional approach (e.g., quantity and relevance of material). The authors found that if the teacher maintains a flexible approach, willing to adjust pace and material based on learner needs and performance, “the learning experience is both enjoyed and is of benefit to the learner” (p. 10). They concluded that “traditional methods being utilized within the new approach environment might be ideal” (p. 10).

2) Mixed-Methodology Using Project-Based Learning (PBL)

Some researchers have reported positive results when implementing a mixed-method course that strategically combined teacher-centered instruction in the form of lectures with PBL (Azer, 2009; Baeten, Dochy, & Struyven, 2013). For example, multiple studies have reported that students have both higher levels of satisfaction and better performance in classes that combine features of direct instruction (i.e., lectures) with PBL (Ellis, Goodyear, Calvo, & Prosser, 2007; González-Marcos, Navaridas-Nalda, Jiminez-Trens, Alba-Elias, & Ordieres-Mere, 2021; Goodyear, Asensio, Jones, Hodgson, & Steeples, 2003). Specifically, Biggs and Tang (2011) state that judicious explanation and instruction by the teacher in a mixed-method classroom can help create an environment where students are comfortable and motivated to learn. It should be noted that González-Marcos et al. (2021) observed that individual student preferences seem to influence student satisfaction with varying types of instruction. Specifically, students who have a higher level of intrinsic interest and/or a certain degree of background knowledge about the subject (i.e., deep learning approach) tend to show more interest in student-centered (PBL) tasks whereas students with higher levels of extrinsic motivation (i.e., surface approach to learning) tend to prefer more direct instruction (Baeten, Dochy, Struyven, Parmentier, & Vanderbruggen, 2016; Dinsmore & Alexander, 2012).

An instructor’s approach and attitude also seem to influence outcomes of the mixed-method approach. Prosser and Trigwell (2014) and González-Marcos et al. (2021) both reported that students’ learning styles tend to mirror the approach of their teacher. That is, when the class becomes teacher-centered, the students will adopt a more passive learning role, but when PBL activities are taking place, the students become more active and interested. Furthermore, Lee and Baird (2021) noted that “teachers play a crucial role in facilitating student engagement in student-centered learning regardless of cultural contexts” (p. 298). The study, and others like it, found that students are more likely to participate when they perceive instructors as supportive figures (Cavanagh et al., 2016) who relinquish some control and let students take more of an ownership role in their own learning (Cook-Sather, 2002), and encourage student-student interaction in a low-structured, low-stakes environment (Kiefer, Alley, & Ellerbrock, 2015).

In terms of specific context, the most interesting study for this author was that of Kim (2015). At a university in South Korea, Kim (2015) performed a semester-long qualitative study with a large class of intermediate Korean EFL students (n = 47), using three tools for data collection–student journals, teacher journals, and interviews. The study reported some positive results, the main one being that PBL and group work encouraged learning and independence in some students. The teacher also reported that student journals are an effective way to collect data. On the other hand, a lack of teacher-centeredness in the course caused a considerable amount of frustration and confusion in both the students and the teacher. As a result, Kim (2015) recommended some degree of teacher-centeredness in future courses in this context. The findings of Kim’s (2015) study are particularly pertinent to the current study. First, Kim (2015) faced difficulty because the learner-centered approach “was foreign to the students and thus alienated them” (p. 82). Specifically, students had linguistic difficulties as well as social difficulties, working in groups that were largely self-guided. Also, while the teacher was freed from the duties of lecturer, the teacher took on more work overall in the form of semester-long journal dialogues and interviews with the students. On the positive side, the students and the teacher were able to overcome their differences for the most part, but some problems (e.g., plagiarism, absenteeism, large class size, and low English level) were particularly difficult to overcome and thus left the author with a whole new set of questions.

Based on the current body of research, there is no one-size-fits-all methodology in terms of teacher versus student-centered approaches, particularly in the Korean classroom. However, it stands to reason that if a teacher in a historically teacher-centered context implements some elements of student-centeredness, the students can not only thrive in the short term, but could also become more independent, inquisitive learners in the future. Moreover, if an educator considers the difficulties that some teachers have faced in trying to implement a mixture of teacher and student-centered approaches, certain safeguards could be put into place that might mitigate such difficulties.

4. Research Questions

The current study mirrors Kim’s (2015) study in several ways. The course is mostly student-centered, using project-based learning activities, and data from student and teacher journals is collected and analyzed qualitatively; however, the current study differs from Kim’s in that this researcher mixes in teacher-centered strategies from the outset of the course. Specifically, the previous study aimed to be entirely student-centered, but “confusion and resistance to the new approach [were] evident from both the teacher and the students” (Kim, 2015, p. 90). Kim (2015) reports that the students came into the classroom initially expecting a traditional, teacher-centered environment, and that the new (student-centered) style left the students confused about their roles as learners. The teacher also felt confused about her shifting role (i.e., from provider of knowledge to facilitator), which led to frustration and confusion in her as well. The teacher and the students were left with a diminished sense of self-efficacy, which led the teacher to report that the class needed “some degree of teacher-centered methods so students can become accustomed to the [student-centered] approach” (Kim, 2015, p. 91). The author of the current study hypothesizes that a more practical approach in a Korean university EFL class would be to implement a mixed-method environment in which the students drive the curriculum, discussion, and activities (student-centered) while the teacher delivers direct instruction (teacher-centered) both judiciously according to perceived needs of the students as well as in response to direct requests from students. The author believes that the mixed-method approach will mitigate many of the difficulties expressed in Kim’s (2015) study. The researcher will provide insight to the following questions:

1) How will the students perceive the mixed-method course?

2) How will the teacher perceive implementation of the mixed-method course?

3) How will the students describe their experience in terms of self-efficacy?

III. METHOD

The current study uses an adaptation of Kim’s (2015) approach and uses three data collection methods–a teacher reflection journal, student reflection journals, and individual student-teacher post-course interviews–as sources for qualitative analysis. As Kim (2015) noted, qualitative research provides an avenue for interpretation and in-depth understanding of student perception within a given context (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005; Van Lier, 1989).

1. Participants

The current course, entitled English through Film and Literature, was developed at a private university in South Korea. The course was offered as a 15-week, once-a-week, 110-minute-long elective intermediate English course in the College of Liberal Arts. All 30 participants voluntarily enrolled in the course and its accompanying study. In addition, the classroom was equipped with a computer with Internet access, a projector and speakers, and all students had access to smart phones, tablets with wireless Internet, and a group chat application (KakaoTalk). The chat application was used for one-on-one, small-group, and whole-class conversations between students and the teacher as well as student-to-student interaction.

The stated objective of the course was to further prepare students for success in global higher education by: 1) fostering critical thinking skills via class discussion and group work; and 2) fostering reading comprehension by introducing Tier 2 vocabulary words. Before the implementation of this study, the researcher sent out a university-wide message outlining the course and inviting students (with a recommended TOEIC score of at least 400) to participate. Final class enrollment was (n = 30), and at the time of the study, all participants’ TOEIC test scores were between 400–600 as requested (M = 468). This score is considered intermediate (https://www.testden.com).

Additionally, the 30 participants came from a total of 14 different majors at the university (see Table 1). The course consisted of mostly first-year (n = 10) and second-year (n = 16) students as well as some third-year (n = 4) students. Finally, the class consisted of a nearly equal amount of male (n = 14) and female (n = 16) students.

2. Overview of the Mixed-Method Course

As suggested by Kim (2015), the researcher planned the course according to Stoller’s (1997) model for a project-based language learning course. The course consisted of three stages: Course Co-Construction, Weekly Tasks and Discussions, and Project Creation and Presentation.

1) Stage I: Course Co-Construction

Stage I lasted for the first two weeks of the course. In Stage I, the students and the teacher spent time negotiating meaning in terms of what the course would look like. Kim (2005) expressed major difficulties due to lack of clear instructions, defined tasks, and a routine and cited Doff (1991), suggesting that clarity would “make group tasks manageable and thus encourage each student to engage in the group work activities” (p. 84). To mitigate the concerns expressed in Kim’s study, this researcher initially made available a specific description of the mixed-method approach, and in subsequent class meetings, provided example tasks and continuously checked for understanding. The teacher and students took part in open-ended conversations to co-construct appropriate tasks and task groups to allow students to define their own success (Almarode & Vandas, 2018; Holmes, 2004). By the end of Stage I, the teacher and students had created a list of course objectives, chosen a film and a novel as class material (see Part 3. Material Selection) and created basic weekly assignment outlines. The revised course objectives (modified from the original version that was included in the course description) were to 1) gain knowledge of American/British vocabulary and idiomatic expressions; 2) gain knowledge about American/British culture and compare it with Korean culture; and 3) make friends from different majors. The class compiled a list of ways that groups could display their knowledge on a weekly basis. The list included weekly vocabulary quizzes; weekly culture quizzes, weekly quizzes about the film and novel, role playing, media creation (e.g., videos, drawing, or audio recordings), and mini presentations.

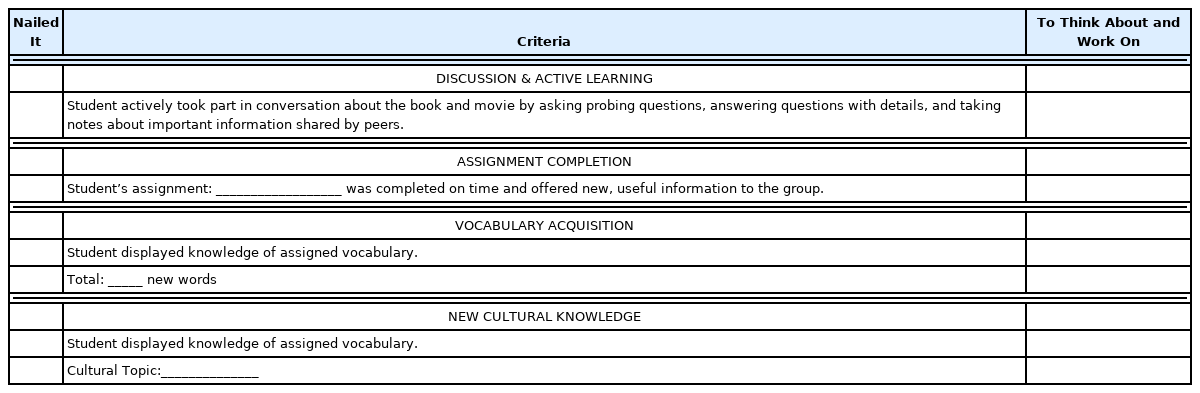

2) Stage II: Weekly Tasks and Discussions

Stage II of the course lasted from Week 3 to Week 9. In this Stage, the class split up into ten groups of three students to perform a variety of tasks. The class chose to work together with the same groups for the entirety of Stage II. The tasks varied from week to week, but mainly, the tasks were created by the students after taking part in weekly, whole-class Socratic discussions and small-group Literature Circles. The weekly Literature Circle groups were formed by combining two groups of three (six total students in each circle). The students decided to do this in order to talk with more students in the class and better accomplish class objective three, which was to make friends. During Stage II, students had access in the classroom to the Internet (via smartphones and the class computer). Students assigned group leaders, which sometimes changed from week to week depending on the group. The leaders, with the help of group members, delegated appropriate tasks when necessary. Some common tasks included entering information into the group’s online content dictionary, creating art for the weekly task, contacting absent group members to inform them about the weekly happenings, and being the main presenter for a given weekly task. The students also assigned Literature Circle roles according to a list provided by the instructor, which was based on the roles described by Morales and Carroll (2015). The groups agreed that peer assessment would be optimal for Stage II tasks and that both peer and teacher assessment would be appropriate for the final projects described in Stage III. Peer assessment took the form of weekly, single-point rubrics (Fluckiger, 2010) that measured four criteria–participation, punctuality, vocabulary knowledge, and cultural knowledge. Specifically, the students were responsible for participating actively in the class and displaying, through discussion, their understanding of the book and the movie as well as newly acquired vocabulary and cultural knowledge. Groups decided the amount of reading and/or viewing they were responsible for each week, and they also decided what kind of activity they would do each week to display their learning. Activities were wide ranging, but the most frequently used activities were role-play activities, quiz games, and standard comprehension and vocabulary quizzes (composed by students, for students). The final project rubric measured the same criteria but was completed by both the teacher and students (see Appendix for detailed criteria).

3) Stage III: Project Creation and Implementation

Stage III lasted for the final six weeks of the course–Weeks 10 through 15. In Week 10, the groups discussed ideas regarding what their final projects would look like. When each group had a working idea of what they wanted to accomplish, we moved to a whole-class group to discuss each group’s plans in more depth as well as to give feedback and tips for moving forward. The teacher prompted the students to think of specific ways by which they could display their knowledge of the book, the films, culture, and vocabulary. The class agreed that the final projects should be evaluated on the same criteria with which the peers assessed each other’s work and participation in the previous weeks. Finally, the groups assigned roles that they deemed equal in terms of workload. Roles varied according to project content. The final projects included: create a children’s book that teaches a lesson based on one of the characters in the book or movie (chosen by three of the ten groups); create an alternate scene from the book or movie and act it out (two of ten groups); write a newspaper article describing a character’s demise (two of ten groups); make a new song about one of the characters (two of ten groups); conduct a podcast interview with (or about) one of the characters/families (one group). It should be noted that we discussed time expectations for the final presentations. The class decided not to issue a time requirement, but that groups should fully display their knowledge according to the rubric and be prepared for a class Q & A session.

In Weeks 11 through 13, groups used various Internet resources and computer software to gather, compile, and analyze information. Some of the groups assigned themselves homework although this was not a requirement. The groups also used class time to rehearse their presentation (if applicable). The teacher used this opportunity to give direct instruction when necessary and/or requested. In Week 14, the teacher provided an optional 2-hour hands-on technology workshop for any students having relevant difficulties. All 30 students attended this meeting, during which we spent time working on technology related issues such as uploading videos to YouTube and making videos private, formatting documents on Microsoft Word and Power Point, and editing audio using Audacity software. In the final week of the course, students delivered their presentations. In between presentations, the teacher and students took a few minutes to fill out rubrics with comments and scores. The teacher allowed students to write comments in Korean or English to ensure time efficiency and accuracy. Weekly participation, student reflection journals, and the final group project accounted for approximately 60, 30, and 10 percent of the students’ total grades for the class, respectively.

4) Teacher Roles

On a weekly basis, the teacher spent approximately the first 15 minutes of each class giving some form of direct instruction. These lessons were usually based on language needs identified in student reflection journals and group conversations. The instructor created additional mini lessons about culture based on student inquiry and interest. As we moved closer to the end of the semester, the teacher gave more direct instruction regarding presentation skills, difficulties associated with technology, and specific issues regarding language (e.g., pronunciation, intonation, volume, etc.). The mini lessons were varied in terms of time and group size. They ranged from 5 to about 20 minutes, and they were delivered to individuals and small groups as well as to the entire class as deemed necessary by the instructor. When the teacher was not delivering direct instruction, he spent the majority of in-class time circulating the classroom, observing and interacting with groups and individuals. The teacher answered questions as necessary, listened to conversations, probed for new information, and offered new questions for consideration when appropriate. The teacher was also the primary DJ in the classroom.

3. Material Selection

In the initial class meeting, participants were notified that they would take the leading role in choosing the class material, group and individual activities, and assessment methods. The first assignment was for students to create a list of appropriate movies that also have book adaptations. First, the students individually brainstormed lists of book-movie combinations. The students were also urged to research more using their smartphones. Then the students formed small groups, combined their lists, and narrowed their lists down to their top-five choices. Finally, we wrote all the titles on the whiteboard. Five titles appeared on the lists more frequently than any of the others, so the class chose to vote on these five titles. The teacher provided sample excerpts from each novel and film script as well as access to popular review websites, imdb.com and goodreads.com, before we finally took a class vote to choose the main material for the course. The class voted via secret ballot, and the teacher and a volunteer student tallied the votes by pulling the ballots out of a box and marking the selections on the whiteboard. The results of the class vote are displayed in Table 2.

As a result of the class vote, materials for this course consisted of two films and a novel. Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (Stuart, 1971) is a film about a young boy named Charlie Bucket who, in an instant, is vaulted from a life of poverty to one where all of his wildest dreams come true. This magical tale was originally written by Roald Dahl in his 1964 novel entitled Charlie & the Chocolate Factory, and later adapted into another film with the same title (Burton, 2005). In a post-vote discussion, the students noted that materials were chosen for the reasons below.

1) Novelty

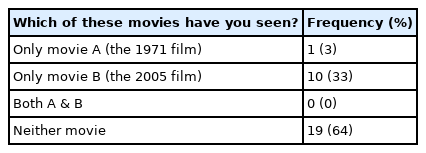

An impromptu survey revealed that only one student had seen the 1971 film, 10 students had seen only the 1995 film, 0 students had seen both movies, and 19 students had not seen either movie. Among the 30 students in the class, none of the students had read the book.

2) Comprehensibility

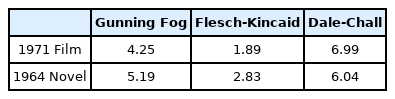

The participants also noted that both the book (Chapter 1) and the movie script (from approximately the six-minute to the nine-minute mark of the movie) were “easier to understand” and “fun”. The author used readability software (https://datayze.com) to analyze the comprehensibility of the 1971 film as well as the novel. In the software, the author took note of three distinct readability scores–the Gunning Fog scale, the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level heuristic, and the Dale-Chall metric. The Gunning Fog scale uses sentence length and syllables per word to measure readability on a scale of 1 to 20 (5 = readable; 10 = hard; 15 = difficult; 20 = very difficult). In this case (see Table 4), the film and the novel measured 4.25 and 5.19, respectively.

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level heuristic indicates that the text can be read by the average student in the specified grade level. In this case, the film and the novel measured 1.89 and 2.83, respectively. Although these scores (grade levels) may seem low, they were the students’ decision, and the instructor chose not to intervene in order to allow the course development to remain as student-centered as possible. The Dale-Chall score further solidified the instructor’s decision not to suggest different reading/viewing material.

Dale-Chall is one of the most accurate readability metrics. This metric incorporates a list of 3,000 easy words which were understood by 80% of fourth-grade students. The readability score is then computed based on how many words present in the passage are not in the list of easy words. A score of 4.9 or lower indicates the passage is easily readable by the average 4th grade student. Scores between 9.0 and 9.9 indicate the passage is at a college level of readability. The film and the novel scored 6.99 and 6.04, respectively.

A final analysis of the material showed that, on average, the texts can be easily read by average elementary school students in native English-speaking countries. The script and the novel measurements according to these formulas can be viewed in Table 4.

3) Entertainment Value

The 1971 film and the 1964 novel scored 7.8 (of 10) and 4.4 (of 5) on popular review websites imdb.com and goodreads.com, respectively. The movie was the second highest rated among the five candidates, and the book was the highest rated among the five candidates, which gave the combination the highest score. There are no official criteria for rating films and books on these websites; however, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (Stuart, 1971), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Burton, 2005), and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Dahl & Schindelman, 1964) have over 200,000, almost 500,000, and nearly 800,000 reviews, respectively, and each piece has either won or been nominated for multiple awards. See Table 5 for some examples of nominations and awards for the two films and the novel.

IV. DATA COLLECTION METHODS

1. Teacher Reflection Journal

During and after each weekly class meeting, the author took both in the midst (post-it) notes and after the fact (a teaching journal) notes to document thoughts about class events (Power, 1996). Nunan (1992) noted that such teacher reflections can offer holistic insight into the course (i.e., the material, the students, and the research itself). The author paid special attention to his own thoughts and feelings as well as the perceived emotions and efficacy of the material and lesson plans. The researcher followed Kim (2015) in using Shafer’s (1995) “observation/reflection/plan” journaling format. At the end of each weekly meeting, the researcher wrote out longer summaries of the feelings and/or events captured on the post-it notes to ensure that information would remain clear and memorable in the long term.

2. Student Reflection Journals

The author gave learners a fifteen-minute reflection period at the end of each week’s class to write in their reflection journals. Reflection journals are useful in the classroom for a variety of reasons. First, if kept regularly, reflective journals can allow students to “evoke conversations with self,” view their own learning patterns, reflect on the things they do not know, and recognize the areas of study where they need to devote more time (Hiemstra, 2001, p.19). The researcher asked the students to think about the following questions in hopes that the students might start an inner dialogue: What went well? What didn’t go well?

In addition, reflection journals offer students the opportunity to develop self-awareness and critical thinking skills (Nabhan, 2016). Mlynarczyk (2013) asserted that “journals give students extensive writing practice, the opportunity to express [themselves] and … the chance to develop a personal relationship with the teacher” (p. 36). This part of the journal was of particular interest to the instructor because it allowed the students to voice their opinions, providing ample material for data as well as opportunities to reconceptualize the course from week to week. For this section of the reflection journal, the teacher had students fill out a simple What you already Know–What you want to Know–What you Learned (KWL) chart (Evans, 2020) along with a prompt for extra comments.

Finally, in the context of ELT, Nunan (1992) examines several studies regarding journaling (by both students and teachers) in the language classroom and concludes that “journals are important introspective tools in language research” (p. 118). In the current study, student journals were not assessed according to grammatical accuracy or richness of vocabulary; however, in some cases, they gave the teacher insight in terms of the necessity for mini lessons from week to week. In the current study, students were prompted to use either their L1 or L2 (whichever felt more comfortable) in the journals for accuracy’s sake, but as noted below (see part V. Result), most of the journal entries were composed in English.

3. Individual Student-Teacher Interviews

At the conclusion of the course, the researcher conducted open-ended interviews with each student in the class. The open-ended interview structure allowed the researcher to “follow up interesting developments and to let the interviewee elaborate on various issues” (Dörnyei, 2007, p. 136). Interviews ranged from 15 to 30 minutes in length. The interviews were not mandatory, but all 30 students participated in an interview either in person or on Zoom, which was made an option for convenience’s sake. All of the interviews were recorded with permission from the participants, and the researcher took notes to highlight new and/or supplementary information as suggested by Nunan (1992).

4. Data Analysis Methods

Following the work of Kim (2015), the method of qualitative data analysis for the present study was “working with data, organizing it, breaking it into manageable units, synthesizing it, searching for patterns, discovering what is important and what is to be learned, and deciding what you will tell others” (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998, p. 157). To ensure inter-coder reliability, the researcher and two separate coders (assistants) carefully examined the qualitative data. First, in order to get as comprehensive a view of the data as possible, all the journals (teacher and students) as well as interview transcripts and notes were transcribed to Microsoft Word documents. Any data that was written in the students’ L1 was translated into English by the two research assistants after transcription. The researcher then verified the translation with the help of a third assistant when necessary.

Three identical sets of data were printed, and each coder then independently used a recursive and iterative content analyzation process to identify codes in the data that were either relevant to the research questions of this study or otherwise deemed significant. The coders then performed an intense thematic analysis, marking and labeling any significant lines or terms in the texts. Finally, the coders cut and filed the pieces of paper to further identify themes. Several times throughout the analyzation process, the coders met to discuss and negotiate the meanings of their findings. The coders estimated inter-coder reliability at 84 percent using a simple percentage agreement calculation in Microsoft Excel. The coders chose this method of estimation for its ease of use and simplicity (Feng, 2014) and because the text was simple enough that it did not require a high level of precision (Krippendorff, 2013; Zhao, Liu, & Deng, 2013).

V. RESULT

1. Student Perception of Self-Efficacy in the Mixed-Method Course

As described, the current report was based on Kim’s (2015) study which examined participants in a student-centered Korean university EFL context. This researcher expected that explicitly addressing the issues that the former researcher faced would help mitigate said issues, which included “confusion and resistance” (p. 87), “low participation” (p. 83), “vague direction” (p. 84), and “absenteeism” (p. 87). For the most part, the current study did eliminate these issues, but some problems and difficulties did arise. The major findings are as follows.

1) Interaction With the Teacher

The overwhelming majority of student journal entries noted their surprise and pleasure about being able to interact with the teacher directly on a weekly basis. Students noted that they often felt shy to ask the teacher questions or otherwise interact with the teacher during class time in front of their peers. Specifically, students made comments such as “it’s hard to think about what to say when I’m with the professor” (Project journal: Student 05–Week 03) or “I’m okay to make mistakes in [my journal] because the teacher can help me” (Project journal: Student 23–Week 06). Moreover, they felt positive about being able to develop a relationship with the teacher through private journal entries. One important takeaway from these findings is that students did not display the same type of anxiety as the participants in Kim’s (2015) study. In response to a teacher comment in a mid-semester journal asking specifically how group work was going and how the group members were getting along, several students answered with comments similar to, “I didn’t feel stress. I like my group and I know what I have to do every day” (Project journal: Student 11–Week 09). In a post-semester interview, the researcher followed up on these answers and received responses that included such phrases as “clear directions” and “easy to understand what to do” and “everyone had a job” (Interview: Students 11, 23, 24, respectively). In this regard, the results of the current study also differed from those of Kim (2005). Constant dialogue between the teacher starting in the first week of the course and continuing to the end served as a safety net for the students, thus lessening anxiety about things like language disparity and fear of falling behind or completing an assignment incorrectly.

Jung and Cho (2019) mentioned that, among other factors, an instructor’s emotional involvement with the class is a component of effective instruction. Furthermore, Lee and Baird (2021) found that “instructors who build trust with their students can help them buy in to new activities” (p. 299). Of course, in any student-teacher interaction, a certain power dynamic will be present; however, these researchers (i.e., the coding team) found themes that indicate that the rapport between the teacher and the students was largely, if not entirely, genuine. First, the vast majority of the students’ journal entries were written in English despite the teacher’s explicit direction to use their L1 (Korean) if doing so felt more comfortable for them. The total number of journal entries for the semester was (n = 361), and the total number of journal entries written primarily in English was (n = 339), which was approximately a 94% rate of English entries. There were no direct comments from the students regarding why they made this choice, but the researchers surmised that there were two main reasons: 1) the students wanted to use the journals as an opportunity to practice their English, and 2) in using English, the students felt a sense of freedom in that they were not confined to the hierarchical structure of the Korean language. It should be noted that both of the research assistants in this study were Korean and former students of the researcher. In discussing the themes of the qualitative data, both research assistants agreed that they feel more comfortable talking about personal issues with their foreign professors than with their Korean professors. This of course is a tiny sample size of anecdotal evidence, but at the very least, it offers some basis for future inquiry.

Another major theme was that of doodling. In 27 of the 30 journals, students included some type of doodle or drawing in more than one entry. In more than half of the journals (17 of 30), students included doodles or drawings in almost all of their entries. Of the doodles and drawings, all of them were deemed positive by the researchers. Most of the doodles were emojis expressing happy thoughts or emotions. A few students drew sad emojis, but in all of these cases, the students expressed sadness over, for example, missing a class or not performing as well as they thought they could in a certain activity. Therefore, the researchers viewed these emojis as positive as well because they expressed passion about the class and not necessarily negative stress. Finally, ten of the journals included stickers, and six of the journals included portrait of the teacher. The teacher was smiling in all six portraits. The researchers believe that the low-stakes nature of the communication in the journals as well as in the classroom led to honest, positive rapport between the teacher and the students (Kiefer et al., 2015).

A final aside, one of the objectives of the course, which were co-composed by the students and the teacher, was to make friends. Although we never explicitly measured student friendship formation, anecdotal evidence in the form of student journal entries as well as teacher observation indicate that the objective was indeed accomplished.

2) Comfortable Classroom Environment

An unexpected result of data analysis was just how important the classroom environment was to the students, particularly in terms of background music. Week after week, students made comments suggesting music or praising music choice. They said that the music made them feel more open to talk with their peers without the awkward silence that sometimes happens in normal conversation classes. Comments included such statements as “it’s like a café!” (Project journal: Student 15–Week 08) and “I always tap my feet in the group, but it’s okay because we are smiling and the teacher is okay” (Interview: Student 11). In fact, many students even recommended or requested songs during class or in their reflection journals. These results seem to support Van Horn’s (2020) study that found that students perceive themselves as better students in the presence of background music. Music choice included a wide variety of genres from upbeat K-pop songs to lo-fi instrumental music.

The teacher took a flexible mindset into the class each day, always willing to follow the flow of the conversation and make any changes or readjustments necessary to enhance learning and the comfort of the learners, and as a result, the learners seemed to enjoy and benefit from the experience, showing self-confidence in their interactions (Burns & Goldie, 2000). Similarly, the students’ continuous willingness to interact with their peers during class and to interact with the instructor both in the classroom and via reflection journals indicates that the students perceive the instructor as a supportive figure (Cavanagh et al., 2016).

The researcher came away with two interesting questions after examining this part of the data. First, would Kim’s (2015) study have had different results if the instructor had played music during the class? Second, how much of a factor is the teacher’s character and demeanor in determining the eventual success or failure of a lesson or course? Lee and Baird (2021) wrote about how the teacher plays a major role in getting students engaged regardless of cultural context. Any positive outcomes of the current study must be tested again by different teachers in different contexts to begin to find answers to these questions.

3) Intrinsic Motivation to Read

As Cook-Sather (2002) mentioned, students are likely to participate more in class activities when they take an ownership role in the curriculum, and that is precisely what the students were able to do in this course. They chose the book and soon started to “enjoy the relationship between [characters]” because “it reminds me of my grandfather who died last year” (Project journal: Student 19–Week 09). The students start building intrinsic interest in the stories, and soon they have finished the entire novel, and they are saying things like “this is the first whole English book I have ever finished in my life” (Project journal: Student 02–Week 13) and “now I’m gonna go to the library more, I think” (Project journal: Student 14–Week 13). These findings mirror those of Tsai (2012), who talked about the positive stimulus that reading can become in students’ lives.

4) Cultural Awareness

Another major finding was student positivity toward learning about culture. The material of the course (i.e., the film and the novel) provided a window into Western culture for the students. As a result, several journal entries throughout the semester dealt with Western-style parenting, education, family matters, and business. The subject matter in the journals was a major driver of class discussion (including some direct, teacher-centered lessons about culture), and evidence of learning during these discussions was present in all of the final projects at the end of the semester.

Blasco et al. (2015) talked about how movies can touch students on an emotional level and contribute to self-reflection in learners. Self-reflection in terms of cultural awareness was evident in most student reflection journals. Specifically, students often mentioned how they would like to adopt certain aspects of different cultures and make them a part of their own personal cultures. One notable entry read, “I feel like if I take all the good things from every culture, I can be better and better continuously” (Project journal: Student 01–Week 12). This comment sparked vibrant conversation in the class, and in subsequent weekly journals there was an influx of comments about students hoping to improve their lives by taking things from fashion to manners to food from other cultures and making these things parts of their own lives. It should be noted that students also took a great deal of pride in aspects of their own culture, saying things like “I like junk food, but Korea has slow food that makes families eat and enjoy together” (Project journal: Student 27–Week 05) and “I’m happy because if I’m old or sick I can stay in a hospital and I don’t have to bother my family because of money” (Project journal: Student 19–Week 06). The students clearly reflected upon ideas and issues in the book and the movies, compared the situations with their own lives, and expressed their feelings clearly, usually in the target language. This outcome supports Vincent (2016) who pointed out how movies can help learners think and talk about human concerns in the language they are learning.

Finally, the students asked a considerable amount of culture related questions in their reflection journals and during class discussion. For example, several students asked about family units and when it is appropriate to live together. Other students asked questions like, “Did you [teacher] have a job in middle school?” (Project journal: Student 11–Week 03) or “What is the difference between Korean and American weddings and funerals?” (Project journal: Student 12–Week 07). One student who asked more questions than most also asked the researcher a question during the postcourse interview. He remembered the instructor talking about using a daily to-do list in order to accomplish personal goals. During the interview, he asked specifically, “What is on your to-do list, sir?” (Interview: Student 10). When he and the researcher discussed the contents of the list, the student said that he feels that people from other cultures “have more [intrinsic] motivation to improve their lives, and [he wants] to be like that” (Interview: Student 10). This interview does not reflect data from other students, but this comment is one the instructor plans to use as a catalyst for conversation in future courses.

5) Direct Language Instruction

It should be noted that no codes regarding direct language instruction were present in the student journals. After 15 weeks of no comments on this aspect of the course, the researcher felt obligated to ask about students’ opinions during the post-course interviews. Comments were mostly neutral, lacking any particularly positive or negative tones, expressions, or gestures. The most common answers said something like, “The professor’s teaching makes us comfortable” (Interview: Student 30) or “I could understand what you were teaching, so I feel like I can use it later” (Interview: Student 24).

The researcher feels that it is important to note here that no news seems to be good news. Students tend to take on a passive role when the teacher adopts teacher-centered methods (Prosser & Trigwell, 2014). During the periods of direct instruction, the teacher did not take in the midst notes, but in hindsight, the teacher does not recall feeling any negative emotions during direct instruction. On the contrary, a reexamination of the teacher’s refection journal found comments like “students were engaged” (Teacher journal: Week 05) and “several students had follow-up questions” (Teacher journal: Week 07) when reporting the results of direct instruction. One comment said, “sometimes the kids just want to hear a TED Talk, and that’s okay!” (Teacher journal: Week 10). The takeaway here is that a predominantly student-centered class, particularly one that is over 100-minutes long and in an EFL setting, can be mentally exhausting. Sometimes students need to be passive, which is why it is understandable when researchers like Emaliana (2017) report that while student-centered classrooms are surely beneficial, they can also be unhelpful at times.

6) Absenteeism

As was the case in Kim’s (2015) study, several students missed several classes during the first few weeks of the semester. In fact, all but two students missed at least one class during the first five weeks of the semester despite a teacher statement at the beginning of the semester as well as a clause in the course syllabus stressing the importance of regular attendance. This phenomenon is not new to the teacher, so he was not surprised at this result. However, high absence rates led to some disjointedness initially. At the beginning of the course, the teacher made sure that all members of the class were included in a group chat on our class group chat application. Even so, some students found it “hard to catch up” (Interview: Student 09) when they missed a class or stated that group members who were absent “made the group slow and stressful sometimes” (Interview: Student 30).

2. Teacher Perception of the Mixed-Method Course

As stated before, the researcher used previous research to help mitigate some of the concerns present in Kim’s (2015) study. The outcomes were mostly positive; however, the teacher did face some issues.

1) Absenteeism

The high rate of student absence, particularly in the beginning of the semester seemed to be more detrimental to the instructor than the students. While some students did express fatigue or stress regarding either being absent or dealing with absent group members, in comparison with the teacher’s reports, these comments were not highly prevalent in the students’ journals or interviews. The teacher often felt significant stress for several reasons. First, student autonomy (coupled with the large class size) left the teacher feeling like he did not have a firm grasp on the specifics of what the students in each group were accomplishing daily. The students’ journals did give the instructor a window into the basics, but it was difficult to, for example, call a student who was absent in for private office hours as the instructor might do in a smaller and/or more teacher-centered class. Moreover, the teacher felt a sense of helplessness in that he could not do much to help the group catch their absent member up during the class. The instructor could not offer the (few) students who expressed difficulty in their journals any tangible help aside from a reassurance that their grade would not be negatively affected. One teacher comment sums up the teacher’s sentiment well:

I want to write an article in the school newspaper urging clubs and departments to respect other teachers’ classes. We’re trying to do our jobs, but people are stepping all over any potential progress with dodgeball and soccer… and I can’t do anything about it! (Teacher journal: Week 02)

The teacher’s concern about the high absence rate, as evidenced above, led to frustration and a low sense of self-efficacy in terms of being able to properly control the course. The teacher’s negativity subsided significantly as the semester went on, and the teacher was particularly positive toward the end of the semester when post-it notes for 6 of the last 7 weeks of the semester read, “Everyone is here today!” (Teacher journal: Weeks 09, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15). The researcher attributes this success in terms of attendance to constant reiteration to the students about accountability to their group. “I tried my best to come to class for my group” (Interview: Student 22).

2) Workload

This study–which included the teacher reading around 30 student journals each week, writing in his own journal, holding regular office hours with students, and finally conducting over 8 hours of post-semester interviews–was time consuming and stressful. The instructor did his best to offer thoughtful replies to the students in their journals each week, and in doing so, helped the students have a positive experience in the class as evidenced by all the positive feedback he received. However, maintaining such a schedule for one class among a full course load is unsustainable. More often than not, post-lesson journal entries included comments like: “The lesson went well again today. The rapport is growing among the students, and they seem to be cooperating and running a smooth operation… but now [I have to read] these journals” (Teacher journal: Week 07). Kim (2015) noted that the workload does not decrease with a student-centered approach, and this researcher agrees. Furthermore, we both agree that although student-reflection journals can be highly effective (Nunan, 1992; Kim, 2015; Power, 1996), the workload can become overwhelming.

3) Teacher Self-Efficacy due to Direct Instruction

Each week, the instructor offered about 15-minutes of direct instruction at the beginning of class. The instructor also sat down with groups and individuals from time to time to offer mini lessons about language errors observed in student journals and during class discussion. Generally, the teacher felt a good sense of self-efficacy about the lessons, noting occasionally that “it’s good to do something meaningful” (Teacher journal: Week 04) or “[She]’s finally displaying understanding of the concept” (Teacher journal: Week 06). There were no pre or post-tests as a part of this study, so this sense of self-efficacy within the instructor is speculative.

The instructor found that judicious direct instruction in certain instances throughout the semester not only reduced cognitive load on the students, but also saved time. In one of the final journal entries of the semester, the instructor wrote at length about his own biases regarding the balance between student-centered and teacher-centered instruction in the EFL classroom. The main gist of the passage was just what the data in this study seems to reveal. Instructors must know when to shift the center of a learning experience to make it as comfortable as possible for everyone.

VI. CONCLUSION

A considerable amount of research exists that describes Korean students as passive learners who have difficulty taking part in communicative activities that require critical thought (Choi & Rhee, 2013; Lee, Fraser, & Fisher, 2003; Lee & Sriraman, 2013; Park, 2015; Ramos, 2014). However, the current study has provided a small counter to that argument. Lee and Baird (2021) rightly point out that learners and teachers have struggled with a steep learning curve due to national educational policy shifts toward more student-centered methods; however, the researchers also assert that teachers can play a role in facilitating student-centered learning regardless of cultural context. In order to do so, the teacher must take steps to create the ideal learning environment.

This study asked about student and teacher perception of the mixed-method course as well as students’ sense of their own self-efficacy. Generally, the results were positive. The data suggests that the overall mood of the class was pleasant and comfortable. Students participated actively from week to week, and they gave positive feedback in their reflection journals as well as in the post-course interviews. Student feedback showed that they enjoyed interacting with each other and with the teacher. Aside from a workload that was a bit overwhelming at times, the teacher’s feelings mirrored those of the students. The teacher looked forward to attending class each week, and also enjoyed reading reflection journals and talking to the students in interviews despite the time obligation.

There are several possible reasons for the generally positive perception. The first is that the PBL model coupled well with judicious direct instruction to form an effective mixed-method course. In this course, the instructor made clear from the very beginning that the students would drive the curriculum. The students chose the course material as well as the spectrum of projects from which they could choose to display their knowledge. As a result, the students had some measure of inherent interest in the course, which continuously prompted natural questions and observations. In addition, the instructor was provided with authentic topics upon which to base lessons every week. In other words, the direct instruction from the instructor was exactly what the students wanted. Furthermore, the students showed signs of retaining information from lessons given throughout the semester when they presented their projects at the end of the semester.

Relatedly, the lessons (both content and language-based) that the teacher was able to give throughout the semester evoked a significant sense of self-efficacy in the teacher. During the lessons, the students were attentive and showed signs of active listening. Later, as mentioned before, the students were able to display their newly acquired knowledge in the form of presentations, which reaffirmed the teacher’s positive feelings. And although the students did not give many comments regarding the language lessons specifically, the teacher felt positive about this as well. The reasoning behind the positive feelings is that even though the students sometimes displayed struggles with language, they did not express stress. Rather, when prompted, they gave answers that showed they were satisfied with the level of instruction and scaffolding provided. In other words, the direct instruction seemed to give the students a sense of comfort and self-efficacy.

The course content was effective as well. The teacher and the students co-constructed learning objectives at the beginning of the course. The objectives were to learn language and culture through movies and a book. After analyzing the data, it was clear to the researcher that the students had a generally positive attitude about their achievements. The students were genuinely intrigued by the class material, and each week, the class used relevant vocabulary and expressions to have active discussions about cultural topics present in the films and the book.

In this researcher’s opinion, the most important outcome of this study was the apparent student satisfaction with the class atmosphere, particularly the music. A large body of evidence exists that shows how background music can contribute to students’ sense of self-efficacy (Van Horn, 2020), and the current study adds to that body of research. Specifically, through music, the teacher was able to create a low-stakes atmosphere where the students could explore ideas and communicate freely (Kiefer et al., 2015). Therefore, this instructor will continue to use music to contribute to positive learning experiences in future classes.

The current study did have some limitations and difficulties. First, the teacher often observed the use of target language during class activities, discussions, presentations, and in the reflection journals; however, the present study did not include an accurate measure of language acquisition. A future study of this type could include a quantitative element such as a pre and post-test to accurately measure the effect this type of course can have on language acquisition.

Relatedly, there was no measure of the students’ intrinsic motivation. There is no way to know if the generally positive findings of this study in terms of self-efficacy were simply due to a generally positive and motivated group of students. The latter case would support González-Marcos et al. (2021), who found that students with a higher degree of intrinsic motivation tend to perform better in a student-centered, project-based learning environment. The characteristic of motivation is one that should be measured beforehand in studies like this one.

In hindsight, the researcher feels that the teacher should have played a bigger part in designing the rubrics for assessment. The researcher feels that the rubrics that were co-created by the students were a bit too simple and thus failed to accurately assess the students in terms of cultural knowledge and language acquisition.

The journaling aspect of the study had mixed results. For the students, the ability to interact directly with the teacher gave them a sense of comfort and self-efficacy, which supports the research of Mlynarczyk (2013). On the other hand, while the teacher did enjoy communicating with students in this way, and the journals also provided ample material for meaningful weekly lessons, the workload was extreme and unsustainable. In the future, this researcher plans to include dialogue journals (Valizadeh, 2021) as a regular part of the curriculum, but journal collection will be staggered. That is, the teacher will only read and reply to a percentage of journals each week.

Finally, perhaps the most significant limitation of the current study is the sample size. The class was only 30 students, and the study only lasted one semester with only one teacher. Whether we agree with it or not, Korea is shifting toward a student-centered approach to learning on a national level. If this shift is to be successful, teachers need more training, resources, and perhaps most importantly, high-quality professional learning/experience in the classroom. Moreover, it stands to reason that students who are not accustomed to the student-centered context would benefit from a gradual implementation of new methods as opposed to a sudden shift in classroom activities and expectations, so more studies like this one are needed in a variety of contexts throughout the country.