Low-Level Students’ Perspectives Toward Synchronous and Asynchronous Blended Learning Activities in the Post-Pandemic Era

Article information

Abstract

Entering the post-pandemic era, educators at universities across South Korea dealt with many restrictions and challenges transitioning back to face-to-face courses. To overcome these difficulties, some instructors used their experiences during emergency remote teaching to incorporate more blended learning activities. This study aimed to gain insight into low-level students’ perspectives toward participating in online synchronous and online asynchronous activities during an in-person EFL course in the first semester of 2022. A total of 83 students participated in this study by completing a series of surveys composed of a mix of Likert-scale and semi-structured qualitative questions. Data analysis combined descriptive statistical analysis with qualitative analysis based on the creation of themes and categories. Key findings are as follows: first, learners enjoyed both types of blended learning activities but preferred asynchronous discussion boards; second, low-level learners believe synchronous activities can help improve their listening skills, while asynchronous activities provide valuable chances to read and write; third, low-level students will accept an activity if they perceive it has value, and these learners have their own opinions of how to make the activities better. Specific comments and examples related to student perspectives and suggestions for the future use of blended learning activities are discussed.

I. INTRODUCTION

Entering the first semester of the 2022 academic calendar (i.e., March 2022), many South Korean university students and professors were prepared to re-enter their traditional classroom setting after two years of emergency remote learning/teaching. While this forced online environment initially led to many difficulties, such as internet and technology issues, lack of interactions, or challenges transferring face-to-face curricula online (Basri et al., 2021; Famularsih, 2020), learners and educators were able to adapt over time. For instructors, adjustments were made to improve the dispersal of course contents while attempting to increase interactions between teachers-students and students-students. Examples of these changes included the use of learning management systems (LMSs) to organize courses (Almusharraf & Khahro, 2020), the usage of synchronous or asynchronous approaches to benefit instruction (Han, 2021; Hong & Kim, 2022), and the development of collaborative or flipped-style activities that used online features such as discussion boards (DBs) or Zoom meetings to encourage more student-centered classes (Irvin & Im, 2022; Irvin, Park, et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2020). Therefore, educators who worked hard to develop their technological knowledge and skills during the pandemic era of teaching should have returned to their conventional classrooms filled with confidence.

However, when taking their first step into their post-pandemic-era reality, learners and educators were not greeted by a traditional classroom. Instead, strict social distancing policies meant that desks were not only spaced further apart but also plexiglass dividers were attached, making it difficult for students to see the board or interact with their peers. Moreover, mask mandates were put into place, with instructors encouraged by administrators to follow these protective measures closely. These policies resulted in educators needing to quickly adjust their curriculums and instructional methods to that semester’s norm. Luckily, the instructors who had successfully adapted during the pandemic era now had an answer to their latest problem. Their solution would be using blended learning (BL) approaches and activities to maintain high levels of interactions and collaboration. Again, motivated instructors were fortunate that discourse regarding suggestions and best practices (Park & Park, 2022) was already being held with academic circles. The next step would be to determine which modalities (e.g., synchronous or asynchronous) and types of BL activities (e.g., Zoom meetings, DBs) would be utilized.

For educators in South Korea, several recently published articles related to pandemic-era BL instruction and activities could be extremely beneficial in helping them adjust to post-pandemic teaching. These studies include an emphasis on interactions (Han, 2021), Flipped Learning and how it can be used as BL (Kim & Chun, 2022), and satisfaction (Hong & Kim, 2022), among other factors. Yet, while these findings are noteworthy and could be helpful, they were conducted during online or emergency remote teaching. Therefore, while the previous results lay a strong foundation for online learning or BL, additional research is required to know learners’ perspectives of BL activities in the new post-pandemic-era classrooms. Moreover, educators in South Korea looking for specific studies with practical examples of using synchronous and asynchronous BL activities in the post-pandemic era will have a difficult time because the number is limited. Instead, much of the current post-pandemic research in South Korea focuses on either the factors that need to be considered when integrating BL, with a heavy emphasis placed on learner-instructor interactions (Min, 2022), or a small number of studies that have analyzed how synchronous or asynchronous BL activities affect Korean adults or university students since returning to face-to-face instruction (Heo et al., 2022; Im, 2022). Therefore, targeted research, which emphasizes and examines synchronous and asynchronous BL activities used inside a post-pandemic-era classroom, is greatly needed to add to the current academic discourse.

Thus, this study was developed to consider learners’ perceptions of participating in synchronous and asynchronous BL activities during post-pandemic-era face-to-face classes. Specifically, participants were low-level students from one of five sections of a first-year General English EFL course conducted during the first semester of 2022 (i.e., March 2022). Prior research was used to develop a theoretical framework and a series of surveys completed throughout a 15-week semester. The surveys used a mix of Likert-scale and open-response questions, which were then analyzed through quantitative descriptive statistical analysis and thematic qualitative methods. Moreover, the results combined numerical findings (e.g., frequency, mean, or standard deviation) with participants’ direct quotes to gain greater insight into learner experience. Lastly, this study attempts to add to the current educational discourse towards synchronous and asynchronous BL activities by sharing first-hand experiences during the post-pandemic era. To guide this project, the following four research questions were created.

1. What were low-level students’ reported enjoyment levels immediately following two online synchronous and two online asynchronous blended learning activities in their first-year EFL course?

2. What were the perceived pros and cons identified by the low-level student completing synchronous and asynchronous blended learning activities in their first-year EFL course?

3. What were low-level students’ reported satisfaction levels and perceived areas of improvement towards synchronous and asynchronous blended learning activities in their first-year EFL course?

4. What were the perceived strengths and weaknesses and suggestions for improvement by low-level students completing synchronous and asynchronous blended learning activities in their first-year EFL course?

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Theoretical Framework: Collaborative Learning (CL) & Blended Learning (BL)

To begin answering this study’s research questions, a foundational knowledge of current educational trends is needed. Among the many transformations that occurred over the past two decades, incorporating more and more forms of technologies and an increased emphasis on shifting towards student-centered instructional models are two of the biggest. For instance, scholars from the United States identify that today’s learners are digital natives who can grow much more through self-directed learning and would benefit from changing the traditional school approach (Nair, 2019). Moreover, as the technology acceptance model (TAM) has gained more and more credibility, researchers continue to analyze and create taxonomies that identify factors that will lead to learners accepting or rejecting specific technologies selected by instructors (Kemp et al., 2019). Yet, when attempting to combine student-centered learning with TAM, factors such as interactions, collaborations, and BL are necessary to consider.

Regardless of the type of course (i.e., face-to-face, online, or hybrid), interactions are a prerequisite. The previous statement is rooted in social learning theories and social constructivism, which assert that learning occurs through a combination of social interactions and experiences (Bandura & Walters, 1977; Vygotsky, 1978). Due to social interactions with teachers or peers, learners involved in the social learning process also engage in collaborative learning (CL). Moreover, as educators’ understanding of CL and classroom interactions continued to evolve, three main types of interactions were identified. These three types are student-student, student-teacher, and student-content (Moore & Kearsley, 1996). Additionally, even as traditional face-to-face classes were adapted for distance and online learning, the three types of interactions were still present (Anderson, 2004; Bernard et al., 2009). Therefore, each of the three interaction types is important to the success or failure of learning for individual students, but in the case of synchronous or asynchronous activities that ask learners to engage in CL with peers, student-student interactions are most important.

Next, in addition to CL, another way that educators are creating more student-centered courses is through the use of BL instructional methods and activities. As current learners are considered digital natives who often have a variety of knowledge and experience working with different technologies, BL classes that employ student-centered approaches allow individual learners to build work with others, build interpersonal skills, and become teachers themselves (Xu et al., 2020). In addition, as Lee (2017, p. 2) stated, “Blended learning can be an effective way to help facilitate active learning and reinforce concepts taught in the face-to-face class.” Therefore, even before pandemic-era teaching, high-quality examples of BL can lead to greater learner satisfaction, higher rates of participation, and increased cooperation among peers (Klemsen & Seong, 2012; Lee, 2017). In the next section, pandemic-era research related to BL and CL will be introduced.

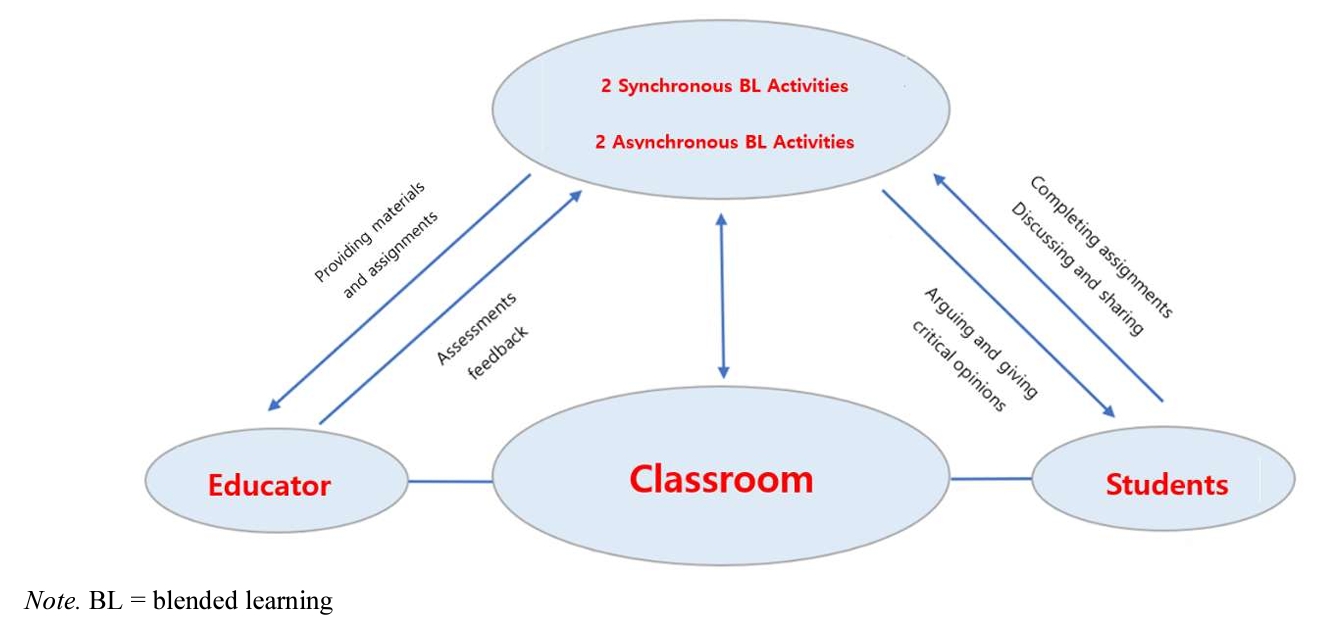

Lastly, to organize the above educational theories with the overall aim of this study, a BL activities map was constructed. Adapted from the work of Kang and Zhang (2023), Figure 1 introduces the main flow of this study. In the center of the map is “Classroom,” as this was the primary learning environment for student-student, studentteacher, and student-content interactions. However, since this study attempted to gain insights into learners’ perceptions of synchronous and asynchronous BL activities during the post-pandemic era, participants took part in four separate online BL activities (i.e., two synchronous activities using Zoom and two asynchronous activities using DBs). Therefore, while the classroom was the primary environment for students to interact with their instructor and content, the online activities were opportunities for participants to interact with their peers. Additionally, the university’s LMS was used to remind students of the activities’ expectations, to collect all completed assignments, and to provide targeted feedback to the learners after completion.

Relationship Between BL Activities and Classroom Teaching (Adapted from Kang & Zhang, 2023)

2. BL Research Prior to the Pandemic Era

Leading up to the pandemic era, many scholars analyzed the role digital technologies could have on traditional learning or which teaching style was best for online learning. Regarding digital technologies, Bond et al.’s (2020) systematic map research of 243 studies published between 2007 and 2016 discovered many inconsistencies with research methods and findings. However, with regards to BL, Bond’s team found that online discussion forums or DBs were the most frequently used, and the most common targeted audience was undergraduates who could benefit from higher engagement and satisfaction (Bond et al., 2020). Concerning online education, the modality of the teaching style was consistently being analyzed and adapted. The benefits and drawbacks of both synchronous and asynchronous approaches were judged based on student perceptions (Malik et al., 2017). Based on the research results from Kim (2015), Korean university participants’ most prominent difficulty was the lack of interactions at all levels. Specifically, it was noted that learners desired more face-to-face interactions with peers to build trust and knowledge, wanted an increase in the total number of interactions with the instructor, and craved a decrease in the level of the content and number of assignments to better match their skill level (Kim, 2015). On the other side of the argument, according to Lee (2017), Korean EFL students can have greater class satisfaction and enjoyment when using an asynchronous online DB activity. These increases are the result of proper planning by the instructor to establish and encourage more student-student interactions, leading learners to share their unique opinions, build their knowledge from their peers, create collective knowledge, and increase critical thinking (Lee, 2017). Lastly, over time, the discourse changed from which modality was better to what would happen if synchronous and asynchronous activities were combined into BL approaches. Based on a literature review of 36 EFL studies from 2015 to the start of the pandemic conducted by the research team of Cahyani et al. (2021), BL was superior as it created a student-centered environment that allowed each learner to succeed, as long as they had functioning technology.

3. BL Research During the Pandemic Era

For those unfamiliar with education, the wealth of knowledge presented in the previous section could imply that all instructors had the necessary knowledge and skillset to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic. However, that was not the case. Instead, problems such as internet access, slow internet connections, difficulties sharing or exchanging materials, and challenges using unfamiliar information and communication technology (ICT) tools arose for many learners (Famularsih, 2020). Additionally, students struggled with isolation and feelings of “self-studying” due to the lack of interactions between them and their peers and instructors (Irvin & Park, 2021). Fortunately, as the pandemic continued to evolve, so did educators. As Rachman et al. (2021) suggested, emergency remote teaching became a new norm for teachers and learners, which required new strategies to overcome new challenges. Moreover, as instructors’ confidence grew, they could implement more student-centered approaches (Xu et al., 2020) that utilized synchronous and asynchronous approaches. For example, Riwayatiningsih and Sulistyani’s (2020) research of 55 students enrolled in English writing classes found that participants were satisfied with both modalities. Learners’ satisfaction and enjoyment were tied to their perceptions of feeling more connected to the material while being afforded numerous CL opportunities (Riwayatiningsih & Sulistyani, 2020). Additionally, improvements to universities’ LMSs allowed for greater student-instructor and student-content interactions (Almusharraf & Khahro, 2020). In addition, individual instructors were able to tailor BL activities to specific courses. For instance, in a class whose goals were focused on reading to learn new vocabulary and pronunciation to increase fluency, using Flipped Learning videos with synchronous class meetings led to more engaged and active learners (Kim & Chun, 2022).

Similar to scholars around the world, academics in South Korea identified strengths and deficiencies to improve the quality of emergency remote teaching methods. For instance, a meta-analysis of 138 articles from 2015 to September 2020 by Bae and Lee (2021) summarized effective online teaching methods, emphasized the importance of educational domains (e.g., social interactions), and stressed the importance of specific sub-elements to learning (e.g., satisfaction, participation, problem-solving, among others). These findings continued to be verified and expanded on through additional research that focused on instructional modality, including how social and cognitive presence can help increase satisfaction with online asynchronous activities (Hong & Kim, 2022) or how proper curriculum design is needed to scaffold online synchronous activities so that learners can work in smaller groups and gain a greater grasp of the content (Han, 2021). Moreover, educators focused on increasing the number of studentstudent interactions found success with varied approaches. For example, collaborative asynchronous online DB activities led to increases in student satisfaction, especially group satisfaction, because it was a chance to meet with others, share opinions, gain knowledge from peers, and improve all 4-major skills (i.e., reading, writing, speaking, and listening) through typed posts and student-created videos (Irvin & Im, 2022). Also, collaborative synchronous online meetings through Zoom led to enjoyment for student-led groups who felt free to talk with peers but apprehensive towards completing tasks correctly, while teacher-led groups felt less free to express their opinions but satisfied that they would be correctly finishing their tasks and could ask questions to the instructor (Irvin et al., 2021).

4. BL Research Aimed at the Post-Pandemic Era

More recent trends in the field of education have focused on how BL instructional methods and activities can be integrated into the post-pandemic era (Park & Park, 2022). One example is that of Min (2022), who reaffirmed that learner satisfaction is an important measure to understand future BL usage but that more student-instructor interactions are needed for greater enjoyment and engagement. However, while this study aimed to give learners choices and increase student-teacher interactions, more research on student-student interactions is needed.

Another relevant example for this study, because it also used BL activities in a face-to-face course during the postpandemic era, is Im (2022). In this quantitative study, 144 first-year EFL students at a Korean university had increased enjoyment and satisfaction towards asynchronous online DB activities because they had more interactions, increased motivation, and higher academic achievement based on a pre-and post-test. On the other hand, negative results were reported related to learners not experiencing a decrease in stress or improvements to their self-directed learning (Im, 2022). Yet, while this example perfectly fits the scope of this research study, the number of other projects analyzing and determining best practices for using synchronous and asynchronous BL activities is limited, especially using both modalities in the same study. Therefore, this study aims to add to the current gap in research by focusing on actual experiences and feedback provided by low-level learners enrolled in a first-year EFL course that integrated synchronous and asynchronous BL activities to increase collaboration amongst peers.

III. METHODS

1. Setting and Participants

This study took place at a large, private Korean university during the first semester of 2022. Before the start of the semester, administrators at the school determined that most classes would return to face-to-face instruction. However, to create a safe learning environment, students and instructors were asked to follow strict social distancing protocols, including mask mandates. Additionally, plexiglass dividers were attached to desks to provide another layer of protection. These environmental and procedural changes are notable as they were unique to the time of this study and may not be the current standard. However, as educators continue to understand the post-pandemic paradigm, this author believes the findings from this study are still applicable to the current situation and any future emergencies.

In total, 83 students participated in this study. All participants were freshmen enrolled in a first-year compulsory General English course required for graduation (i.e., the requirements at the university states students are required to take two 3-credit hour EFL courses). The first-year curriculum includes College English 1 (CE1) during the first semester and College English 2 (CE2) during the second semester. Participants in this study were enrolled in one of five low-level CE1 sections in which the author was also the instructor. For this study, the sample was composed of 45 females and 38 males. Their ages ranged from 19 to 24 years old, with 69 out of 83 (83%) reporting they were 20 years old in Korean age. Lastly, a student’s major is often a primary reason for selecting a particular section number, so it is typical for learners from the same department or college to be in a class together (e.g., the College of Foreign Languages could have students who are studying English, Spanish, French, etc.). For this study, participants came from the College of Public Health, the College of Scientific Technology, the College of Biotechnology, and the College of Sports Science.

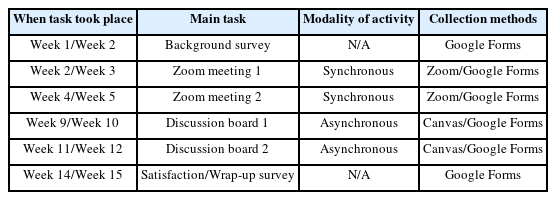

2. Procedures and Individual Tasks

An examination of Table 1 will highlight the procedural timeline used for this study. The 3-credit CE1 course requires 30 separate class meetings (i.e., two 90-minute classes per week). Ideally, the 30-class session would occur within 15 weeks, but due to the start date and national holidays, the semester could be 16 weeks long. The first task completed was an initial survey to gather background information, prior English-speaking experiences, expectations for the course, and perceived skill levels. Then, since this study was focused on synchronous and asynchronous BL activities, four separate activities were planned (i.e., two synchronous meetings and two asynchronous discussions). Before the midterm exam (i.e., weeks 2 through 5), learners participated in two synchronous BL activities using Zoom or Google Meet to complete a task based on a specific topic (see Table 2). Immediately following each Zoom meeting, students were asked to complete a survey to gather instant feedback on their thoughts and experiences. These surveys were a mixture of Yes/No questions (e.g., Did you enjoy this activity?), 5-point Likert-scale questions (i.e., 1 = much less satisfaction to 5 = much more satisfaction), and open-response prompts (e.g., Please explain your experiences taking part in this activity. Or please explain any positive or negative thoughts about the online activity). Next, following the midterm exam but before the final exam (i.e., weeks 9 through 12), students participated in two asynchronous BL activities using the DB feature of the university’s LMS. Similar to the Zoom meetings, participants were asked to complete each DB activity based on a specific topic and task (see Table 2). Once they completed the DB activity, students would again immediately fill out a survey to gather their thoughts and experiences. Lastly, at the end of the semester (i.e., week 14 or 15), a satisfaction/wrap-up survey was conducted. The survey included a mix of Yes/No, 5-point Likert-scale, and open-ended questions to allow participants to summarize their experiences throughout the semester.

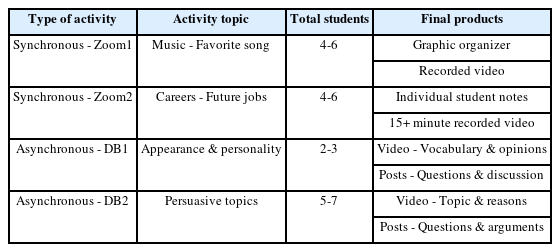

Table 2 was created to add context to this study by introducing the four different tasks. As mentioned in the previous section, the first two BL activities were synchronous using Zoom/Google Meet. Zoom1 consisted of groups of 4 to 6 random partners talking about the topic of music (i.e., introduce your favorite song). Participants were given a graphic organizer before their meetups to help them organize their thoughts. Then, during the meeting, students were expected to listen to their peers and write down the most important details. At the end of Zoom1, each member of the group needed to submit their graphic organizer, and one group leader had to upload a video file of their recorded conversation. Next, random groups of 4 to 6 students were created for Zoom2, and the main topic was future careers (i.e., describe the job you most want in the future). However, unlike Zoom1, participants were told to prepare their notes without a graphic organizer, meet and talk with their group for at least 15 minutes, and write down whatever they felt was most important. Lastly, after Zoom meeting 2, each group member had to upload their activity notes, and the group leader needed to submit a video file of their recorded conversation. Following the midterm exam, the modality of the last two BL activities changed from synchronous to asynchronous. For each of the two asynchronous BL activities, the university’s LMS was used to gather student responses. In addition, since CE1 is a 4-skills class (i.e., reading, writing, speaking, and listening), participants were required to make student-created videos with standard written/typed posts. For DB1, random groups of 2 to 3 students were created to allow participants to learn how to use the LMS’s DB feature, and the topic for the activity was appearance and personality (i.e., describe your personality/appearance and use information from your textbook). Each participant’s first post was a video file that they made giving their thoughts about the topic. This initial post was followed by a series of written/typed responses to ask questions, share opinions, and build knowledge of the topic. Then, a larger random group of 5 to 7 students was created for DB2. The topic for this discussion was a student-selected debate topic (i.e., they could select any topic with two sides of an argument or two separate positions), and their initial post was a student-created video explaining their topic and providing pro and con arguments. This first post was followed by a series of written/typed responses developing arguments for each side of the debate topic.

3. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection for this study consisted of participants filling out surveys. These surveys were created using Google Forms, and there was a combination of Yes/No, 5-point Likert-scale, and open-ended questions. All surveys were developed based on the research questions for this study, and following the creation of each survey, two experts with more than 10 years of teaching experience within the field of EFL higher education were asked to examine each question. Suggested changes to change or eliminate any individual question were agreed upon by the two experts and the main researcher. Next, as participants completed each survey, the submissions were collected and organized into an Excel document. Any student who partially or failed to complete the survey was eliminated from this study. Then, to ensure student anonymity, a random number and the letter “s” (e.g., s1, s2, s3, etc.), were given to each participant. Finally, an analysis of each relevant question based on the best methodological fit was completed.

For research questions 1 and 3, descriptive statistical analysis was used. Specifically, research question 1 was related to participants’ enjoyment by asking whether they enjoyed the activity through a simple Yes/No question. Then, a 5-point Likert-scale question (i.e., 1 = much less satisfaction to 5 = much more satisfaction) was asked to determine which style of BL activity (i.e., synchronous Zoom1 and Zoom2 or asynchronous DB1 and DB2) were participants more satisfied with. Next, research question 3 used a series of 5-point Likert-scale questions to reveal participants’ perceptions towards which activity type was the most challenging, what activity modality led to the most perceived improvements, and which of the 4-skills (i.e., reading, writing, speaking, and listening) did students fell improved the most during each of the activities. To analyze this data, Microsoft Excel was used to determine the basic numerical responses of the participants (Kaur et al., 2018). These findings included mean and standard deviation for each question, which was then organized through Microsoft Excel to create bar graphs as visuals/figures for the results below.

Unlike questions 1 and 3, research questions 2 and 4 relied on qualitative analysis of participants’ responses to open-ended questions on all the surveys. The goal of these questions was to allow students to share their experiences and give their feelings/opinions to construct an accurate picture of what happened (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994) during the synchronous and asynchronous BL activities. Moreover, by combining descriptive statistical questions with qualitative ones, this study aimed to add to the numerical distribution by eliciting many detailed responses to describe the cognitions and behaviors of individuals in this study (Jansen, 2010). To accomplish these objectives, data results were collected and analyzed through thematic, descriptive, and inductive procedures with non-statistical analysis (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994). For research question 2, as participants completed their surveys, major themes related to the perceived pros and cons for each BL activity style were created. Yet, as this thematic process is an ongoing one, the initial themes and categories will expand and change with additional data, including the addition of new themes and categories (Merriam, 1998). Lastly, for research question 4, similar qualitative approaches were utilized related to the perceived strengths and weaknesses of the different activities. However, because these responses were based on the final survey, they became more of a summary of the participants’ entire experience. Therefore, similar themes and categories were found between questions 2 and 4. These similarities caused question 4’s results to be final quotes that summarize the overall thoughts and experiences of the participants.

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Based on the main research questions of this study combined with the methods presented in the previous section, the results of this paper have been organized into four main categories: 1. Low-Level Students’ Reported Enjoyment Level Immediately Following Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities; 2. Low-Level Students’ Perceived Pros and Cons of Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities; 3. Low-Level Students’ Preferences Towards Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities And Perceived Personal Skill Improvements; 4. Low-Level Students’ Perceived Strengths and Weaknesses of Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities. Following the results for each of the four sections, a final section will be dedicated to the implications of this study.

1. Low-Level Students’ Reported Enjoyment Level Immediately Following Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities

1) General/Enjoyment Completing the Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities

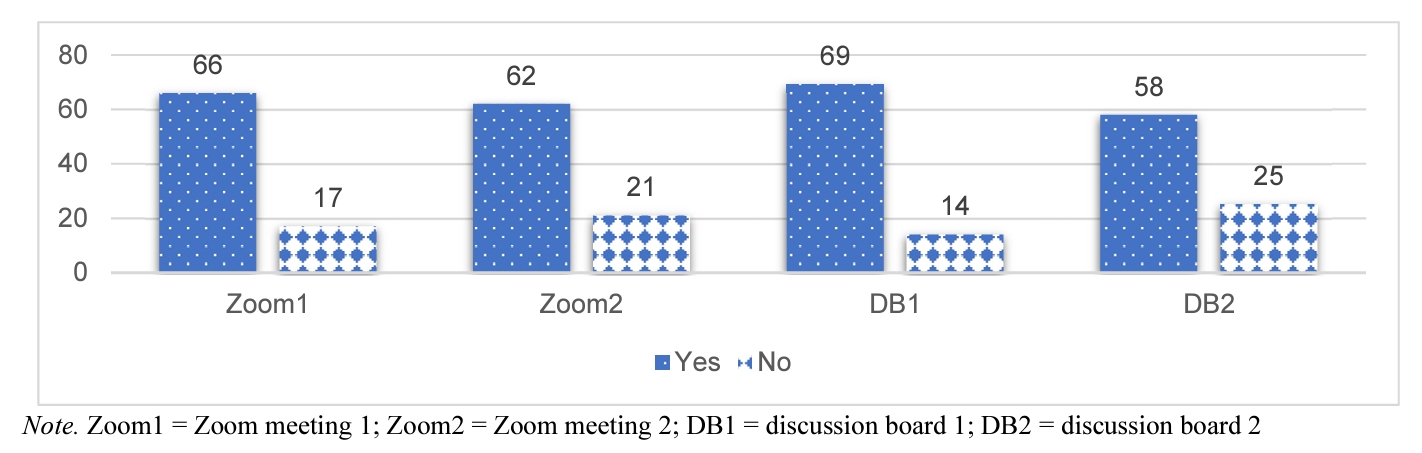

With regards to the information in Figure 2, student enjoyment level was collected after each activity (i.e., Zoom1, Zoom2, DB1, and DB2) based on participant responses to the question of whether they enjoyed the activity. Looking at Figure 2, for each of the four activities, the enjoyment level was higher than the dissatisfaction (i.e., Zoom1 [n = 66]; Zoom2 [n = 62]; DB1 [n = 69]; and DB2 [n = 58]). In addition, the first activity for each modality (i.e., Zoom1 = 80%; DB1 = 83%) was higher than the second activity (i.e., Zoom2 = 75%; DB2 = 70%). Lastly, a minimum of 70% reporting that they like each of the four BL activities is a high response rate. This finding is in line with several pandemic-era research findings that suggest synchronous or asynchronous BL activities are enjoyed by students (Han, 2021; Hong & Kim, 2022; Riwayatiningsih & Sulistyani, 2020).

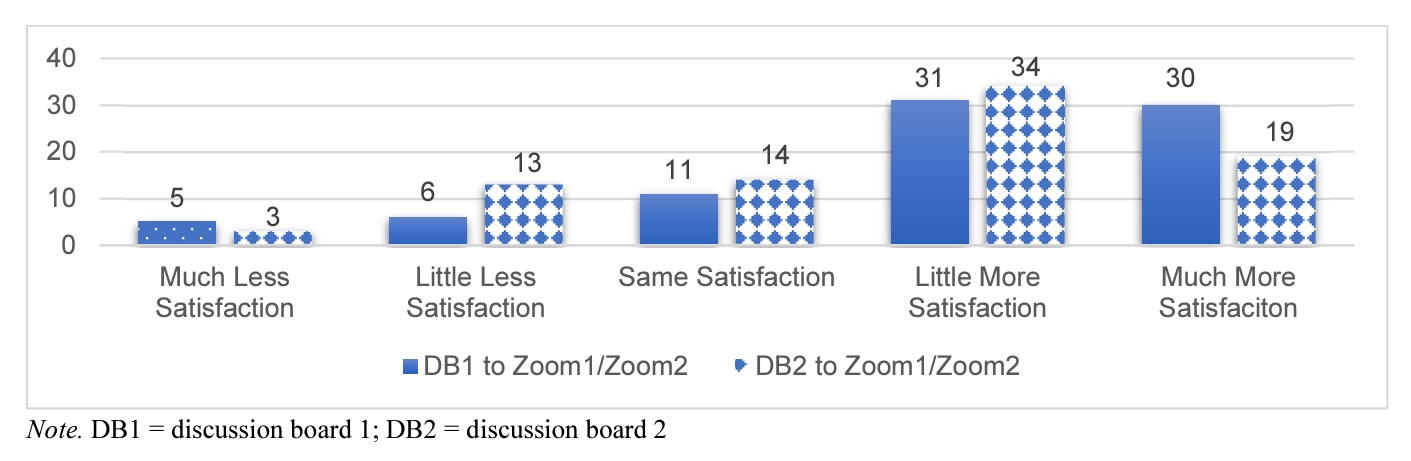

2) Students’ Perceptions of Greater Enjoyment/Satisfaction Between Synchronous and Asynchronous Activities

Knowing that participants generally liked both synchronous and asynchronous BL activities, an additional question was asked to get a sense of learner enjoyment or satisfaction between the two modalities. Additionally, since there was a one-month break between the two modalities, participants were asked to compare the two separate asynchronous DB activities to the synchronous Zoom meetings completed before the midterm exam. The results of this question are found in Figure 3. A majority of participants in this study enjoyed the asynchronous DB activities more than the synchronous Zoom meetings (i.e., DB1 [n = 61] = 74%; DB2 [n = 53] = 64%) had a little more or much more satisfaction compared to the Zoom meetings). This result is notable because while many previous research studies have reaffirmed that learners enjoy synchronous and asynchronous BL activities, they often only use one style per semester or article. In contrast, this study compared the two, so now educators who plan to use more BL activities in the post-pandemic era could assume that selecting DB activities would lead to greater student satisfaction. Yet, caution is needed, as the numbers cannot tell the entire story. Consequently, additional data is required to fully grasp the thoughts and experiences of the participants, which leads to research question 2.

2. Low-Level Students’ Perceived Pros and Cons of Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities

Based on the findings in the previous section, participants in this study were satisfied with the BL activities, but they had a clear preference toward asynchronous rather than synchronous. To better understand these initial findings, each survey included open-ended questions to allow participants to share their thoughts and experiences. The first question invited students to share their experiences participating in each of the four BL activities, while the second question asked them to identify perceived pros and cons for each BL activity style. The results of their responses can be found in this section.

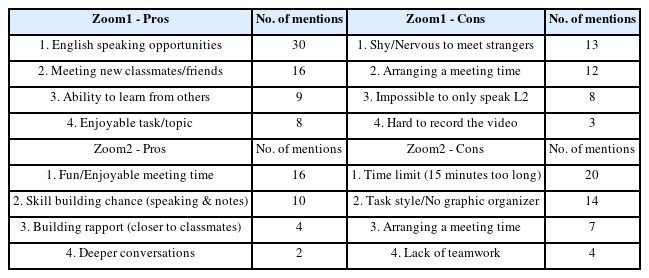

1) Students’ Perceived Pros and Cons Toward Synchronous Zoom BL Activities

Based on the qualitative analysis of student responses following Zoom1 and Zoom2, Table 3 was created to show the perceived pros and cons of participating in synchronous BL activities. Table 3 shows the four most common participant responses for the perceived positives and negatives for Zoom1 and Zoom2. It should be noted that during the thematic analysis, each comment was read and categorized. Consequently, if a single student wrote a response that had more than one of the themes, each mention was counted separately. Therefore, the “No. of Mentions” in Table 3 does not necessarily represent the total number of participants. Finally, to add a greater depth of understanding and provide more insight into the participants’ minds, direct quotes from students have been selected and will be introduced below.

Examining the left side of Table 3, the top four pro themes for the two synchronous BL activities can be seen. Zoom1 turned out to be an ice-breaking activity for the students, with many responses focused on CL and having the chance to speak English. The three most common responses were: 1. Having English speaking opportunities (n = 30); 2. Meeting new classmates/friends (n = 16); and 3. Ability to learn from others (n = 9). These three responses highlight the importance of student-student interactions, even when it is in a foreign language. The final most common pro response for Zoom1 was students enjoyed the topic of music (n = 8). This response shows the importance that studentcontent interactions can have on the enjoyment or satisfaction of the activity. Next, for Zoom2, participants again emphasized the importance of student-student interactions. Yet, due to increased familiarity with their peers, participants were able to go beyond the icebreaking stage. Three of the top four most common responses dealt directly with the enjoyment and interactions between peers (i.e., meeting others was fun/enjoyable [n = 16], students could become closer to their peers [n = 4], and deeper conversations were possible, [n = 2]). The final pro response for Zoom2 identified participants’ ability to have deeper interactions with the content (i.e., building my skills such as speaking and notetaking [n = 10]). Overall, these findings highlight the value learners place on student-student interactions. While initial meetings may be challenging, with more opportunity comes more comfort, which leads to greater rapport and understanding of the materials and skills.

First we can not wear off mask in class so I’m sad, but we can wear off in online meeting and group can see members face. Second, we speak in class little, but we can speak English a lot in online meeting. (s25)1

I was able to find out the genre of songs that my friends liked. And I felt that people had a wide variety of tastes. (s16)

It has the advantage of being able to get to know each other in more detail while asking about the direction of future development. (s79)

But I think my listening, speaking, and writing skills have improved more than in Meeting 1. During Meeting 2, there were words or sentences that I didn’t know, but I was able to solve these problems by asking the other person or looking them up in the dictionary. (s71)

Looking at the right side of Table 3, the top four con themes related to each of the two synchronous BL activities can be seen. For Zoom1, a wider variety of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and technological issues were reported. The two main intrapersonal themes were a feeling of shyness/nervousness because their teammates were strangers (n = 13) and the personal feeling or belief that it was impossible to speak for the entirety of the video in their second language (n = 8). Next, due to the challenge of communicating with unfamiliar peers, the interpersonal difficulty was arranging a meeting time (n = 12). Lastly, a less-mentioned but important theme was the problems associated with one person from each group having to upload their recorded videos to the university’s LMS (n = 3). Interestingly, this number could have been higher because only one person from each group was required to upload the videos. Therefore, if more participants had to learn the skills of recording the video and uploading it to the school’s LMS, it is likely that more technological difficulties would have been reported. Next, for Zoom2, participants still struggled with arranging a time when all team members could meet (n = 7). In addition, not every learner had the same experience with their teammates, as several respondents noted a lack of teamwork between group members was a problem (n = 4). Finally, rather than the technological barriers experienced during Zoom1, participants in Zoom2 noted that the content or assignment was much more difficult (i.e., the assignment time limit was too long [n = 20]; the less structured/lack of a graphic organizer made it more challenging [n = 14]). Overall, these results indicate that teamwork, time management, and technology are potential negatives for synchronous BL activities. However, when given a chance to practice and develop their skills, learners can adjust to BL activities easily. For example, intrapersonal and technology challenges present during Zoom1 were not mentioned in Zoom2. The absence of these comments affirms the pro comments related to building rapport and friendliness while also being able to develop their skills. Yet, these findings remind educators that overly complex or challenging BL activities can overwhelm learners and decrease their enjoyment and motivation.

My personality is introverted. I had a hard time communicating only in English with people watching first. And it was hard to do it online. (s69)

It was the hardest to meet the time with the team members, and it was a little difficult to reach them because they were awkward and unfamiliar. (s2)

The meeting time is long, so I think it gets quiet and awkward during the meeting. So I think it would be good to speed up the conversation and share opinions with each other. (s45)

In online meeting 2, it’s hard to write running notes than online meeting 1. I think writing worksheet is much easier. (s62)

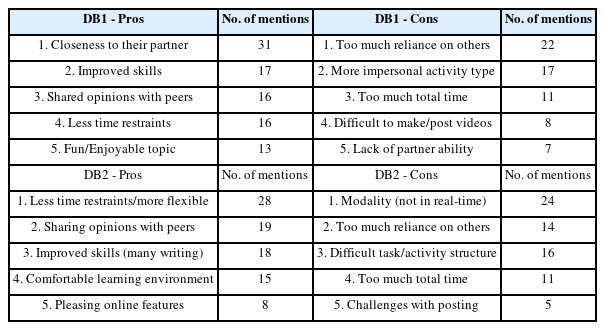

2) Students’ Perceived Pros and Cons Toward Asynchronous DB BL Activities

Following qualitative analysis of the survey results for asynchronous DB1 and DB2, participants’ perceived pros and cons were organized in Table 4. Similar to the previous section, Table 4 consists of the total number of times a theme was mentioned. However, since the DB activities occurred after the midterm and participants were more familiar with the process, respondents’ comments tended to be longer and more detailed. Therefore, Table 4 consists of the top five pro and con categories for the two asynchronous DB activities. Finally, additional student quotes are used to add context to the breakdown of Table 4.

Analyzing the left side of Table 4, the top five pro themes related to each of the two asynchronous BL activities can be seen. For DB1, smaller groups of two or three were created to help overcome potential technology barriers that could occur due to using the DB for the first time. The result of this grouping was the most popular response was participants felt a closeness to their partner (n = 31). Additionally, students appreciated the opportunities to share and learn from each other (n = 16). The last three most popular responses related to the changes in the content and activity’s modality. Firstly, participants appreciated the ability to improve a variety of skills (n = 17). Secondly, the asynchronous nature of this BL activity meant that learners felt fewer time restraints (n = 16) and increased flexibility as to when they would make their posts. Thirdly, many respondents found the topic of DB1 to be fun and enjoyable (n = 13). For DB2, the total number of group members was larger (i.e., 5 to 7 learners per group), but the top three most common responses were the same as DB1 (i.e., fewer time restraints or more flexibility [n = 28]; chances to share opinions with partners [n = 19]; and improved skills [n = 18]). However, with regards to improved skills, many more of the DB2 comments directly identified improvements to their writing skills. The final two most frequent responses for DB2 were related to the modality of the activity and the features of the university’s LMS (i.e., comfortable learning environment [n = 15]; pleasing online features [n = 8]). These two responses highlighted participants’ feelings of comfort towards making written posts and how they were easier or more efficient, even though they were required to make at least one video post. Therefore, these findings imply that low-level learners value having more time and location flexibility to complete BL tasks. Specifically, if given the option, beginning students will opt for reading and writing activities to help build their foundational knowledge and skills.

During posting my opinions and questions, I make my postings myself. So I can improve my thinking skills and my English words and verbs. And sharing my mind with my partner make me more closed with him. (s6)

When using zoom, there was a time limit of 1 hour, so even in the middle of recording, I had to turn it back on and start from the beginning, but this time, I think I was able to do it more comfortably because there was no such limit. And there was no time limit, so I could think more deeply and share opinions. It’s just my opinion, but zoom was a way of talking to each other, so I think my speaking ability is improved more than posting videos and communicating in writing like this time. And it is a big difference to communicate with each other face to face, and I thought this part was a little lacking during this activity. But it was not bad because we talked a lot in class. (s12)

I had a discussion with my main partner and other teams. It was good to exchange comments and feedback on each other’s topics and do assignments. It was best to be able to share various thoughts and opinions of people. In this process, I liked that I could express my opinion in English easily. I could write many different English expressions because I expressed what I wanted to say in English. I realized that my reading skills have improved through this activity. (s31)

Watching videos on each other’s topics was also fun in many ways. And it was new and interesting to write down my thoughts on the subject that the other person decided. And the process of drawing better conclusions as responses to the subject interacted was also attractive. (s70)

The top five con themes related to each of the two asynchronous BL activities can be found on the right side of Table 4. While the previous paragraph and quotations highlighted positives related to interpersonal relationships and the perceived benefits of the new modality, not every student had the same experience. For DB1, two of the top five most common responses dealt with difficulties working with partners (i.e., too much reliance on others [n = 22]; lack of partner ability [n =7]). Thus, while asynchronous BL activities can offer learners time flexibility, this benefit can only be realized if each group member is active and completes their responsibilities. For some participants in this study, time delays and a reduction in the quality of posts were experienced due to poor student-student interactions. The last three most common responses were related to new challenges experienced due to the new BL style and the perceived difficulty of the task (i.e., more impersonal activity type [n = 17]; too much total time to complete the posts [n = 11]; and difficulties to make or post videos [n = 8]). Since CE1 is a 4-skills course, learners were required to make initial videos, which were time-consuming and difficult to make or post on the school’s LMS. Following the initial video post, subsequent written posts allowed for time flexibility but did not have the same connectivity level that was experienced during Zoom1 and Zoom2. For DB2, there were several repeated negatives including too much reliance on others (n = 21), too much total time to complete the activity (n = 11), and the non-real-time nature of the DB led the activity to feel more impersonal (n = 17). However, while many DB1 comments focused on difficulties associated with posting videos, DB2 responses were related to displeasure with the number of total posts required for the BL activity. The larger number of teammates and posts required also affected the interpersonal relationships and student-student reactions as they increased the total time needed to complete the activity completely while also increasing the dependence on peers to get their work done in a timely fashion. Lastly, the final con mentioned for DB2 is how much more challenging it was compared to DB1 (n = 16). In total, time is very important to low-level first-year students. If learners feel their time is being wasted, feelings of contempt can lead to a breakdown of CL. Therefore, educators must plan to overcome these challenges. It begins with developing strong student-content connections so that the assignment does not feel burdensome but also requires active student-instructor interactions to provide feedback and monitor progression to ensure all asynchronous BL activities are running smoothly.

If I use an asynchronous discussion board, I can’t answer when I want to. In other words, when my partner posts the video on the bulletin board, I have to write an answer after that. Because I’m available, but if my partner doesn’t upload the video at that time, I have to wait in the meantime. (s26)

To be honest, I try to speak English somehow when I talk with Zoom or in class. However, while chatting online, I try to write English and if I feel too awkward, I think I use a translator. (s80)

I think it was difficult to improve my English-speaking ability because it was a conversation on the Internet, not a direct conversation. The actual English conversation is to listen and speak right away because if you use the chat window, you think and speak without talking right away. In addition, it was regrettable that the dialogue window was greatly influenced by the other party. (s76)

Due to the large number of people, there were many cases where the opinions that I thought about overlapped when writing comments, and it was a little difficult because there were many comments that had to be posted. (s4)

3. Low-Level Students’ Preference Towards Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities and Perceived Personal Skill Improvements

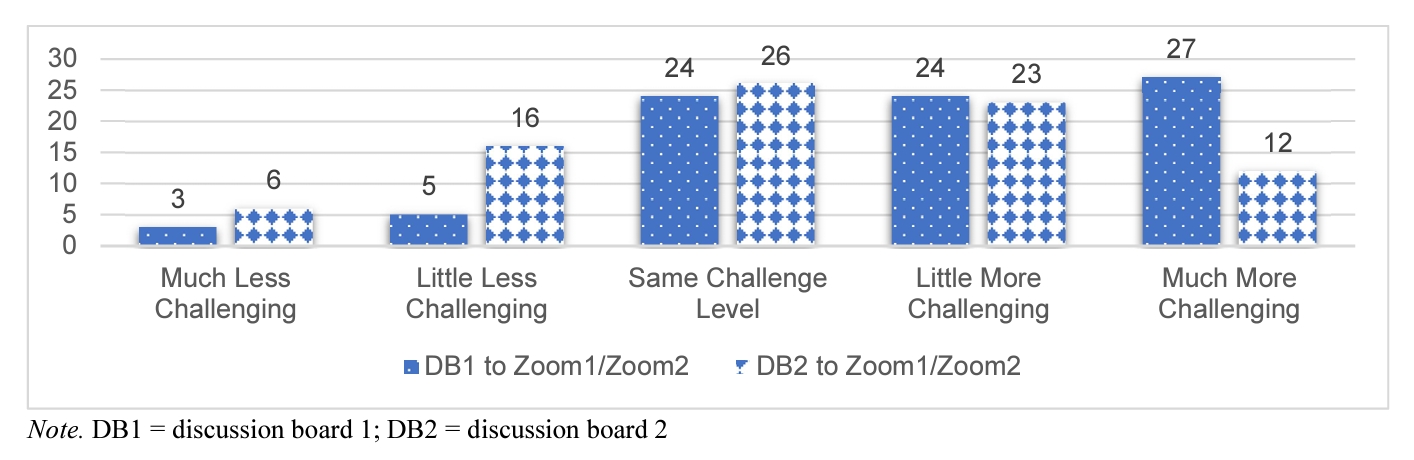

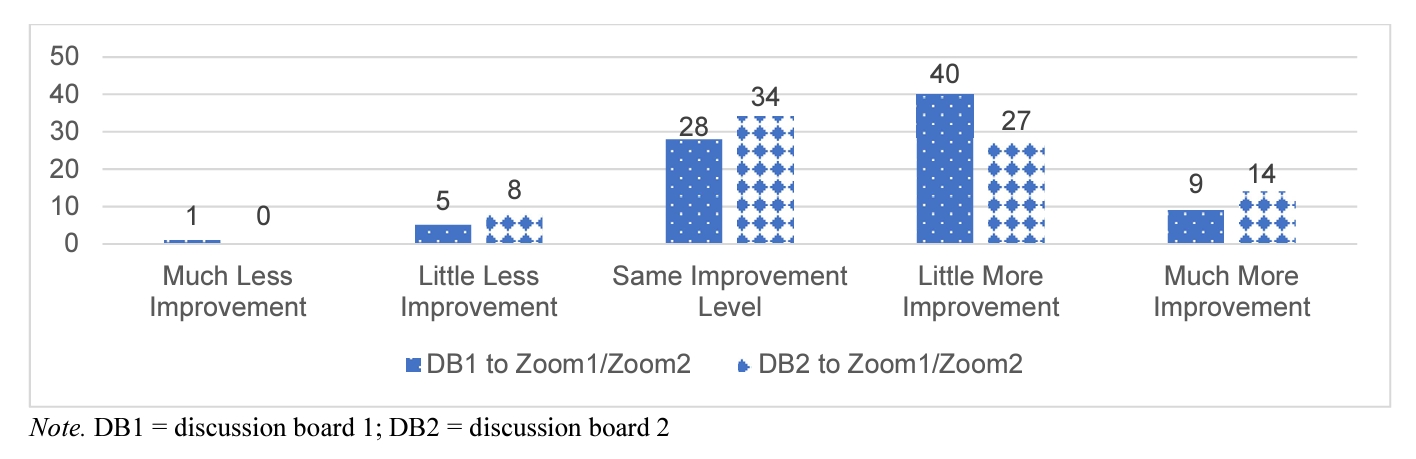

Following the initial two research questions related to participants’ enjoyment/satisfaction and identification of specific pros and cons for each BL activity style, research question 3 was created to further compare synchronous and asynchronous BL activities. Figures 4 and 5 include student responses to survey questions aimed at eliciting perceived difficulty levels and self-reported improvement levels for each activity modality. It should be noted that these questions were asked after the midterm exam, so participants were instructed to compare each of the two asynchronous DB activities to their overall experiences taking part in synchronous Zoom activities. Lastly, Tables 5 and 6 were based on Likert-scale questions from the final survey to gain insights into participants’ overall satisfaction with the two types of BL activities and gather students’ self-reported perceived improvements for each of the four main skills of language learning (i.e., speaking, listening, writing, and reading).

1) Students’ Reported Difficulty Level and Self-Reported Improvement Comparing Asynchronous to Synchronous BL Activities

Examining Figure 4, participants were asked to compare whether they believed the two asynchronous DB activities were more challenging, less challenging, or equally as challenging as the synchronous Zoom meetings. A 5-point Likert-scale question was asked with 1 = much less challenging and 5 = much more challenging. Beginning with DB1, a majority of respondents reported that the asynchronous activity was more challenging than the synchronous one (i.e., [n = 51] or 61% selected a little more or much more challenging). Next, when looking at the bar graph related to DB2, the total number of students who found this activity to be more challenging was less than DB1 (i.e., [n = 35] or 42% chose a little more or much more challenging). However, for both questions, the total number of participants who found asynchronous activities to be less challenging than the synchronous activities was relatively low (i.e., for DB1 compared to Zoom [n = 8] or 10%; for DB2 compared to Zoom [n = 22] or 27%).

In addition to the participants’ self-reported difficulty level, another survey question asked students to compare which type of activity improved their English language skills the most. For this question, a 5-point Likert-scale question (i.e., 1 = much less improvement to 5 = much more improvement) was asked, and the results of this question can be seen in Figure 5. Again, starting with DB1, nearly 60% of respondents believed the DB activity improved their skills more (i.e., [n = 49] or 59% selected little more or much more improvement) compared to the Zoom meetings. As for DB2, this result was lower, with only about 50% of learners saying DB2 improved their skills more than the Zoom activities (i.e., [n = 41] or 49%). Finally, the total number of respondents who found the DB activities led to less improvement was very low (i.e., for DB1 compared to Zoom [n = 6] or 7%; DB2 compared to Zoom [n = 8] or 10%).

Overall, these combined results indicated that participants in this study found the asynchronous DB activities to be more challenging but more rewarding. Therefore, from an instructional point-of-view, it is important to review the DB con list above and the DB weaknesses list below to determine ways to improve asynchronous BL activities. Moreover, caution is needed because learners who feel overwhelmed by the difficulty of an activity could give up. On the other hand, if students feel like their efforts are leading to tangible skill improvements, this can lead to greater motivation and effort in future activities.

2) Students’ Perceived Overall Satisfaction Level and Individual Self-Improvement Throughout the EFL Course

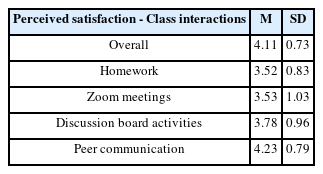

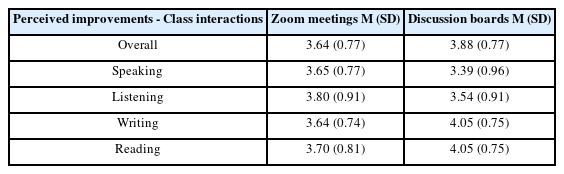

Following the completion of the four different BL activities, learners completed a final satisfaction and overall impressions survey. Included in this survey was a series of 5-point Likert-scale questions asking about perceived satisfaction for the different interactions in class (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) and perceived skill improvements for their overall ability and each of the four main language learning skills (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The results for the questions related to satisfaction can be found in Table 5. Unsurprisingly, the lowest satisfaction was related to homework (i.e., M = 3.52, SD = 0.83). A very close second lowest was the satisfaction towards synchronous Zoom activities (i.e., M = 3.53, SD = 1.03). Next, learner satisfaction with the DB activities was slightly higher than the synchronous Zoom meetings (i.e., M = 3.78, SD = 0.96). However, the two highest satisfaction was reported to be overall satisfaction (i.e., M = 4.11, SD = 0.73) and peer communication satisfaction (M = 4.23, SD = 0.79). These findings are in line with the results for research question 1 that suggested participants have a slight preference towards DB BL activities. Moreover, the high overall satisfaction and satisfaction towards CL indicates that first-year low-level EFL learners find BL activities challenging but recognize their benefits.

Next, the results of the five 5-point Likert-scale questions related to participants’ self-reported improvements during a first-year EFL course using synchronous and asynchronous BL activities can be found in Table 6. The first finding is in line with previous results in this study, as respondents found asynchronous DB activities to be slightly more beneficial than synchronous Zoom meetings (i.e., DB, M = 3.88, SD = 0.77; Zoom, M = 3.64, SD = 0.77). Second, looking at the self-reported perceived improvements of individual skills for the Zoom meetings, listening (i.e., M = 3.80, SD = 0.91) was reported to be the most improved, followed by reading (i.e., M = 3.70, SD = 0.81), speaking (i.e., M = 3.65, SD = 0.77), and writing (i.e., M = 3.64, SD = 0.74). As these activities were synchronous and required learners to speak, it is unsurprisingly that listening is one of the top two. However, based on the earlier findings/student comments related to the pros of the Zoom meetings, the self-reported result for speaking improvements seems low. Third, examining the participants’ responses to perceived individual skill improvements for the asynchronous DB activities, reading and writing improvements were tied for the highest (i.e., reading, M = 4.05, SD = 0.75; writing, M = 4.05, SD = 0.75). Reading and writing were followed by listening (i.e., M = 3.54, SD = 0.91) and speaking (i.e., M = 3.39, SD = 0.96). These findings are consistent with earlier results/participants’ comments suggesting that asynchronous BL activities promote improvements in reading and writing. Furthermore, the higher and more balanced results for reading/writing skills of the asynchronous activities compared to the speaking/listening skills of the synchronous activities are notable.

Overall, the findings of this section confirm many of the earlier results. For example, low-level learners view DB BL activities as valuable chances to develop reading and writing skills, which had the highest total among all the questions. However, while responses to research question 2 implied that low-level learners could develop their speaking skills during synchronous BL activities, this result suggests that the fear of speaking or lack of ability is a major challenge for beginner students. Therefore, instructors should consider synchronous BL activities for icebreaking or brainstorming, while class time should be dedicated to vocabulary and grammar building.

4. Low-Level Students’ Perceived Strengths and Weaknesses of Synchronous/Asynchronous BL Activities

With regard to research question 4, once participants had completed all the activities and post-activity surveys, a final satisfaction and overall improvements survey was completed. This survey includes two open-response questions to gain deeper insight into participants’ experiences, opinions, and suggestions. The first question asked students to describe their perceived strengths and weaknesses of the different BL activities, while the second question attempted to elicit learner suggestions on how to improve the future use of synchronous and asynchronous BL activities.

1) Perceived Strengths and Weaknesses of Synchronous and Asynchronous BL Activities

Building from the earlier findings, many comments focused on the difference between the synchronous versus asynchronous nature of the activity modalities. Student 26’s quote below sums up the most common response, with learners finding the real-time nature of Zoom meetings to be better for getting immediate feedback while also not having to wait or rely on lazy or unmotivated teammates to make their posts was another benefit.

First, the advantage of team activities through zoom meetings is immediate feedback. Rather than team activities using the discussion board, I could immediately express my opinion and expect a response to it. However, the disadvantage is that we have to meet online at a set time and do team activities, so if a team member does not keep time, it will cause damage to everyone. (s26)

The second most common response was related to time. Student 11’s comment touches on the critical aspect of total activity time. A typical Korean first-year student enrolls in numerous courses, which makes their time valuable. Thus, synchronous activities are seen as a time saver because they are completed at one time. On the other hand, depending on the requirements of the asynchronous activity, the amount of time to make initial posts, read peers’ posts, and type additional posts could be time-consuming.

Zoom and DB have opposite strengths and weaknesses. The biggest advantage of zooming is that we don’t spend too much time. However, for people with beginner language skills, real-time communication can make it difficult to understand the contents of the conversation. On the other hand, DBs are understood by writing comments, so they can understand the details more delicately, but they have the disadvantage of taking that long. (s11)

The last most common response was related to the specific skill each BL activity targeted. Student 36’s quote below summarizes learners’ beliefs that synchronous will help speaking while asynchronous will improve writing. As noted in the finding from Table 6, participants reported more improvement in listening rather than speaking for synchronous BL activities. Additionally, throughout this study, low-level respondents have continuously emphasized writing. Therefore, for this group of learners, instructors may want to put more weight on writing than speaking skills when planning their lessons.

Zoom meeting is good because I actually speak English. However, it seems that it did little to improve writing skills because it was written because it had to be written in real time. Conversely, discussion board meeting does not help improve speaking skills because it does not actually speak English. However, it was very helpful for my writing skills because I had a conversation with writing sentences. (s36)

2) Participant Suggestions for Future Use of Synchronous and Asynchronous BL Activities

With regard to the perceived limitation of fewer opportunities for speaking and listening practice during asynchronous DB BL activities, participants in this study did recognize the benefit of student-created videos. Student 12’s comment below starts to address this idea.

The strength of Zoom meetings is that my speaking and listening skills improve. Online DB meetings cannot practice speaking and listening unless I post additional videos. However, if I add the process of talking about it after uploading a video like a task we did, online Discussion Board meetings, such as Zoom meetings, also seem to improve speaking and listening skills. (s12)

As a 4-skills class, the instructor for the CE1 course purposely required an initial student-created video post for both DB1 and DB2. Once a video had been posted, group members were required to watch their peers’ videos to practice English listening. As Student 12’s comment suggests, making these videos provided Englishspeaking/listening opportunities. Obviously, these videos were not in real-time, which does change the dynamic and learning outcomes of the BL activity. However, respondents noted that the videos allowed students to watch and rewatch the videos while becoming more attentive to others’ speech patterns. Therefore, adding student-created videos to asynchronous DB BL activities is suggested to incorporate more skills.

Another common response amongst participants was the need for online BL activities during a face-to-face course. Student 13’s comment below sums up many of the students’ concerns.

I think it’s good to proceed with all the courses in class. As the pandemic ends, meetings will be free, and through this, it will be free to gather in groups during class. Also, if student do some courses as homework, I think there are cases where the assignment cannot be done by a partner. Therefore, I think the whole process of the meeting should be conducted in class. (s13)

This quote and others like it are crucial because they emphasize a major challenge for instructors moving forward in post-pandemic teaching. Namely, as reported above, the average first-year Korean university student’s satisfaction with homework is lower than other measurements. While this result is not surprising, it does mean that learners place the greatest emphasis on learning within the classroom. Yet, as educators teaching in the post-pandemic era, we must continue to build upon the lessons learned during the pandemic and incorporate BL activities that allow for increased CL and student-student interactions.

Lastly, to achieve the goal of integrating more synchronous and asynchronous BL activities in face-to-face courses, efforts need to be made to determine the most effective and efficient methods. Two participant suggestions that highlighted this point came from Student 67 and Student 18.

As in the class format that has been conducted so far, it would be good to conduct a book-oriented class in the face-to-face class, and to use the Zoom meeting or discussion board as a means to communicate in English mainly about the content learned from the book during face-to-face class. (s67) It would not be a bad idea to upload your opinion as a video on the DB and meet in face-to-face classes to share each other’s opinions on the video. Rather than writing each other’s opinions in the comments, I think talking with each other will help with conversation skills. For Zoom meetings, I liked it better to give a clear topic and write down work sheet. (s18)

Student 67’s quote is specifically important for low-level students. The reason is that many beginning learners struggle to comprehend the basics. Thus, a textbook is a necessary scaffolding agent and guide towards skill and knowledge acquisition. A lack of knowledge/skills could also be why low-level students prefer reading/writing. Additionally, Student 18’s suggestion highlights how a synchronous meeting could focus on speaking skills followed by an in-class activity emphasizing writing or vice-versa.

V. DISCUSSIONS AND FUTURE IMPLICATIONS

Several of the findings from this study reaffirm the results of previous research. For example, participants gained enjoyment (El-Sawy, 2018) from participating in synchronous and asynchronous BL activities. Moreover, as learners gained confidence in completing BL activities while interacting with their instructors and peers, their satisfaction rose (Hong & Kim, 2022; Kim & Chun, 2022). Yet, one of the primary goals of this study was to follow the suggestions and call to action from previous scholars to investigate enjoyment, satisfaction, and learner perspectives (Park & Park, 2022) towards the use of synchronous and asynchronous BL activities in a post-pandemic classroom. To that aim, this study purposefully mixed synchronous Zoom meetings with asynchronous DB activities to increase learner interactions between their peers, instructor, and the course’s content during one of the strictest social-distancing periods. In particular, it focused on student-student interactions (Min, 2022) and sought to elicit genuine thoughts, experiences, and comments from first-year low-level EFL students in the post-pandemic world.

The first implication of this study is that today’s digital-native learners can adjust and thrive when provided opportunities to interact using synchronous and asynchronous BL modalities. Prior research has shown that a single modality can increase satisfaction and achievement in the post-pandemic face-to-face classroom (Im, 2022). Moreover, this study reaffirmed Cahyani et al.’s (2021) findings that a BL approach that combines synchronous and asynchronous learning is better than a single style. Yet, rather than just blending online styles, this study proved that mixing synchronous Zoom meetings and asynchronous DB activities is possible. As with any curriculum-design decision, there will be pros and cons, and learners may have their preferences, but students will adapt if given proper guidance. In fact, it is likely future post-pandemic instruction will not be a choice of synchronous or asynchronous but instead a combination of the two, known as bichronous learning (Utomo & Ahsanah, 2022). Therefore, as educators, it will be vital that continued efforts are made to stay up-to-date with the latest technologies and ICT tools. Knowing how to use these tools while being able to help learners utilize them too will help with designing BL activities. To gain the necessary skills and knowledge, teachers must actively participate in workshops and continuously appraise themselves of the latest trends. Moreover, an absence of fear and a willingness to trial and error different combinations of bichronous activities will be essential.

The second implication of this study is that low-level learners have preferences towards reading and writing, but they also will accept more challenging activities as long as tangible improvement can be felt. This result confirms the findings of Spring et al. (2019), who asserted that students’ reasons for enjoying an activity are related to the improvement of their skills. For low-level learners, there is a comfort that comes with using a textbook, emphasizing basic reading and writing skills for standardized tests, and limiting the number of homework assignments or in-class interactions. However, this study demonstrates that low-level learners can be engaged and satisfied with active, student-centered courses emphasizing CL and BL activities. High levels of engagement and satisfaction do not happen the first day, but with thoughtfully designed lessons and encouragement to try, low-level learners will make strides forward. Therefore, for instructors who primarily teach low-level students, efforts should be made to use synchronous Zoom meetings with basic topics near the start of a semester to build a sense of community. Them, as learners become more comfortable and confident, in-class activities can be paired with asynchronous DB activities that are based on a textbook and require student-created videos to allow low-level students more opportunities to develop their reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills.

The third implication of this study is that low-level learners have great ideas and suggestions for improving their courses. This belief is based on the final two participant quotations in section 4.4.2. In the two quotes by student 67 and student 18, sincere recommendations for how future BL activities could be integrated were made. As educators, there are times we can become complacent in our teaching styles or believe full-heartedly that our way is the best. However, in a student-centered classroom, especially one that emphasizes CL and BL, it is critical that we regularly assess our curriculums, instructional methods, and activities. Therefore, for instructors who will consider the use of BL activities in the post-pandemic era, formative and summative evaluation that includes student feedback will be crucial. It is recommended that following each BL activity, formative evaluation should involve learners giving immediate feedback about what they liked and did not like. Then, at the end of the semester, summative evaluation should be based on more student feedback related to enjoyment, satisfaction, perceived improvements, and overall strengths and weaknesses of the BL activities. These assessments, combined with honest personal evaluations and continued effort to build knowledge and skills, will help to create more harmonious, student-centered classrooms.

VI. CONCLUSION

In the end, this study confirmed that much of the research conducted during the pandemic era related to synchronous and asynchronous BL activities is valuable to those instructors attempting to create student-centered utilizing CL and BL in the post-pandemic era. However, it has also answered the call by Korean scholars that suggested the need for practical research that implemented BL activities within the post-pandemic era. In particular, it found that low-level first-year EFL students enjoyed synchronous and asynchronous activities, with DB activities preferred. Moreover, low-level learners feel that Zoom meetings provide opportunities to improve listening skills, while DB activities are the most valuable to improve reading and writing skills, which is most appreciated. However, even when certain activities are perceived to be more challenging, low-level learners will accept the increased difficulty level as long as they feel their skills have improved. Lastly, designing a perfect BL activity is difficult because every learner has their preference, but low-level learners can provide great insights into ways instructors can build their BL activities. While the findings of this study did add to the current discourse on synchronous and asynchronous BL activities in the post-pandemic classroom, there were limitations that future research could address. Firstly, this study was conducted in March of 2022, when social-distancing rules and mask mandates were still heavily enforced. However, while some students and teachers wear masks today, the current situation in South Korea is not the same as in 2022. Therefore, additional research that aims to replicate or enhance this study could be beneficial in determining how BL activities will continue to be integrated as the post-pandemic era continues. Secondly, this study focused only on a small number of low-level students in one specific course. Therefore, additional research that considers a larger number of students across different majors across all levels would be beneficial. Thirdly, this study utilized surveys to gather descriptive statistics and long-response answers to gain insight into students’ perspectives. However, additional research could include different measuring tools and variables. For example, deeper statistical analysis, interviews, or focus groups could broaden the results. Moreover, analysis of factors such as achievement or presence would also be beneficial. Ultimately, as the post-pandemic era is upon us, instructors who use the lessons learned during the pandemic will be able to successfully integrate more synchronous and asynchronous BL activities into their curriculums, resulting in increased learner satisfaction.

Notes

There are many student quotations in this manuscript that contain errors.