|

|

| J Eng Teach Movie Media > Volume 24(1); 2023 > Article |

Abstract

This study measured the effect of using music in the classroom on 42 Japanese EFL studentsŌĆÖ motivation, willingness to communicate (WTC), and shyness, and attempted to examine how these three factors are related. The study also looked at ways of creating a more relaxing and enjoyable, as well as a more effective, classroom environment through the use of music in EFL lessons. For these purposes, a mixed-method research was conducted using webbased Google Forms questionnaires on the first and last days of the fall semester in 2018. Quantitative results showed significant effects on WTC and intrinsic motivation, but not on shyness. The content analysis of qualitative data also revealed that while most of the students were motivated by class activities such as pair work, presentations, and music, some students were not able to overcome their shyness. Both analyses indicate that some L2 learners, if not all, still have difficulty in overcoming the shyness that is associated with Japanese traditional culture. The findings of this study suggest that the cultural background of East Asian students needs to be carefully considered in order to further facilitate a classroom environment where Japanese and Korean students can relax and enjoy themselves.

To date, the significance of L2 learnersŌĆÖ emotional state in the classroom has been pointed out by various scholars (Dewaele et al., 2018; Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014; Gregersen et al., 2014; Imai, 2010; Saito et al., 2018). It has been suggested that emotions and motivation are intertwined, as any motivated action includes certain negative and positive emotions (Teimouri, 2017). Enjoyment, for example, is considered one of the positive emotions in foreign language classrooms (Dewaele, 2011; Saito et al., 2018). Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) postulate that the positive emotions, such as enjoyment, need to be studied more than negative emotions in foreign language learning, stating that ŌĆ£[p]ositive emotion can help dissipate the lingering effects of negative emotional arousal, helping to promote personal resilience in the face of difficultiesŌĆØ (p. 241).

Negative emotions such as anxiety, language anxiety, or foreign language anxiety have also been widely researched in the literature. These negative emotions that are considered affective variables on L2 willingness to communicate (WTC), defined as ŌĆ£a readiness to enter into discourse, at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using a L2ŌĆØ (MacIntyre et al., 1998, p. 547), influence individual difference variables of motivation (Gregersen, 2020; Horwitz & Young, 1991; MacIntyre, 1999; MacIntyre & Gardner, 1991). Learning foreign languages is a fundamentally emotional and psychological process undertaken by individual learners whose learning is affected by both personal traits and situational variables (Gregersen et al., 2014). Therefore, learning a foreign language in the classroom is not only challenging for students but also mentally and emotionally demanding, especially for L2 learners in East-Asian countries. In classrooms in East-Asian countries such as in Japan and Korea, where being silent or reticent is considered a favored attitude, students tend to shrink back and become silent when they are called on by teachers (King, 2013; Saito et al., 2018; Yashima et al., 2018).

The study of shyness as a negative emotion with influence on L2 learning has also been investigated by scholars. The cross-cultural studies conducted by Carducci and Zimbardo (1995) showed that approximately 60% of college students in Japan and Taiwan are considered shy, compared to only 30% of college students in Israel. It has been claimed that student shyness is specifically related to WTC as an affective variable at stages such as ŌĆ£I can speak English in front of the classŌĆØ (MacIntyre et al., 1998). Therefore, the study of shyness must also be included in the research of WTC variables as one of negative emotions that may hinder the process of learning in the classroom. However, little attention has been paid to the relationship between WTC and shyness in the literature of negative emotions (Fallah, 2014). In this regard, the author conducted research to examine whether or not the enjoyable activity of music can potentially reduce shyness and thus increase studentsŌĆÖ WTC and motivation.

This empirical study, therefore, has focused especially on the interrelationship among shyness, motivation, and WTC, and tried to seek ways of creating an enjoyable and effective classroom situation through music with the intention to reduce learnersŌĆÖ shyness.

L2 motivation, discussed for many years among critics, is still considered one of the most significant affective factors in second language acquisition (SLA) (Agawa & Takeuchi, 2016; Deci & Ryan, 1985; D├Črnyei, 2001; D├Črnyei & Ushioda, 2009; Gardner, 1985; Noels et al., 1999; Ueki & Takeuchi, 2015). According to self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2002), L2 motivation can be classified into two categories: intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. The former refers to the desire to perform an activity. Thus, students who are intrinsically motivated find the language learning process enjoyable and thereby become more deeply engaged in this process (Kormos et al., 2011; Yashima et al., 2009). The latter refers to a goal that is external to language learning activities and controlled by outside contingencies (Yashima et al., 2009). Extrinsically motivated learners engage in the language learning process mostly because they want to gain a good grade or reward, or to avoid subtractions from the total grade. Of the two types of motivation, intrinsic motivation is desirable and should ideally be reinforced in the classroom language learning process, since it is by autonomous motivation that learners engage in activities such as pairwork more volitionally (Deci & Gagne, 2005).

In terms of the relationship between motivation and emotions, much attention has recently been paid to the dynamic mechanism that emphasizes motivationŌĆÖs effects on foreign language learning, including the L2 motivational selfsystem, since the future selves of L2 learners are affected by both personal and situational traits through different emotional reactions (Dewaele et al., 2019; Teimouri, 2017). The present study, therefore, examines L2 learners in a dynamic situation where they are challenged by many tasks slightly beyond their level of competence (Saito et al., 2018), and attempts to discover whether certain tasks can enhance their intrinsic motivation.

Many researchers have examined variables on WTC, and discovered new affective variables such as perceived communicative competence, age and sex (Kang, 2005; MacIntyre et al., 2002), and attitudes toward international posture in EFL classrooms (Yashima, 2002). Originally developed in first language communication research, the WTC construct has been modified to fit second language learning by adjusting to a wide range of uncertainty inherent in anxious situations (Weaver, 2005). Recent research has noted that various affective factors such as motivation, emotions, and classroom environment influence L2 learnersŌĆÖ WTC (Dewaele & Dewaele, 2017; Garcia & Mora, 2019). Indeed, L2 communication involves many affective variables that influence the development of language acquisition, including the psychological, social, and cultural aspects of L2 speakers with a person or persons with whom she or he talks. Therefore, recent research has investigated WTC as a complex dynamic system where the situational nature of WTC emerges while examining trait-like WTC patterns with both personality and situational traits as important variables of WTC (Peng & Woodrow, 2010; Yashima et al., 2018).

This study also investigates both personality and situational traits in a classroom environment in L2 WTC, and observes studentsŌĆÖ willingness to engage in activities such as interviews, presentations, singing songs, and communicating with others in L2.

Shyness is a controversial topic within the study of second language acquisition and the psychology of personality (Afshan et al., 2015; Crozier, 2005; Pilkonis, 1977; Sette et al., 2019). At universities, freshmen have the opportunity to meet new friends and teachers, and socialize with other members of their department. However, if students are shy, their difficulty in communicating with new people on campus causes them to become silent or inactive in a new environment. Consequently, shy students find it challenging to talk or socialize with new people.

Recent cross-cultural comparative studies in shyness have revealed that the level of shyness varies remarkably across different cultural groups and students from different countries, thereby raising the possibility that shyness is influenced by the culture where the students has grown up in (Afshan et al., 2015). As Griffiths et al. (2014) suggest, while mentioning the warning of generalization of people and cultures, students in East Asian countries such as Japan, China, or Korea have grown up in Confucian heritage cultures (CHC) and tend to be affected by its ideological base that emphasizes the importance of family, harmonious social relationship, and respect for elders, especially teachers. An investigation of oral participation apprehension in the EFL classroom in Taiwan also revealed that an interpersonal barrier to participation as a fear of speaking before others is caused by feelings of unease, nervousness, or shyness (Hsu, 2015). This study also considers that student shyness is one of the barriers to oral communication in the classroom, and, thus, is a significant variable effect to be eliminated. For that goal, the present study incorporates a definition of shyness suggested by Cheek (1989) as ŌĆ£a temporary emotional reaction triggered by encountering new people and situationsŌĆØ (p. xv), and attempts to identify methods to make classrooms more enjoyable and relaxing so that learners will be able to reduce their shyness and finally become willing to communicate with peers as well as teachers.

Music has been used in various forms in L2 classrooms for years, and its merit has been discussed among many researchers (Higgins et al., 2020; Larsen-Freeman, 1985; MacIntyre et al., 2012; Maley, 1987). MacIntyre et al. (2012) note that both music and language are strong markers of culture and can be considered complementary aspects of the human communication tool kit. They further suggest that playing music can be an effective method of creating a relaxing and enjoyable environment in the classroom. Garcia and Mora (2019) and Kitaoka (2021) posit that playing music is especially beneficial when accompanied by visual images of promotional videos by which L2 learners may have an opportunity to learn not only English pronunciation or expressiveness but also to gain a better understanding of cultural differences by seeing buildings, nature, visual images, as well as people living in the locations where the videos were filmed. Although the use of music in the classroom as a means of motivating L2 learners has been researched before, previous studies have not focused on the use of music and promotional videos that affect studentsŌĆÖ motivation, WTC, and shyness. This study examines, therefore, the effectiveness of using music and the accompanying promotional videos to reduce studentsŌĆÖ shyness and enhance motivation and WTC.

This study aims to reveal whether or not music and its accompanying promotional videos enhance studentsŌĆÖ motivation and WTC and reduce studentsŌĆÖ shyness in the classroom. Three research questions were addressed:

1) Can the use of music in classrooms motivate L2 learners?

2) Can activities using music and a related music video reduce studentsŌĆÖ shyness?

3) Can activities using music and a related music video enhance studentsŌĆÖ WTC?

To investigate studentsŌĆÖ motivation, WTC, and shyness, this research used a mixed methods approach.

A total of 42 students in two classes of a university in Japan participated in the study, with each class consisting of 21 students (female n = 22, male n = 20). Majoring in Human Life Science and Physics, the 42 participants were second-year students ranging in age from 19 to 22. The participants were allocated to the highest-level classes by the test they had taken the previous year. According to their self-assessments, their level of English proficiency varied from the third grade to the second grade on the EIKEN Test (Practical English proficiency) and from a score of 500 to 810 on the TOEIC test. Approximately 20% of the participants said that they had previously stayed or lived abroad. Their periods of stay ranged from two days to one month, with no students living abroad for more than one month.

Fifteen lessons were held within the 2018 fall semester in the CALL classroom. Each class was approximately 90 minutes in duration. From the second lesson to the eleventh lesson, students practiced basic English pronunciation. As well, students completed many pairwork tasks throughout the semester in order for them to become accustomed to talking with classmates and teachers in English, as well as to become interested in foreign cultures. The class procedures conducted in the research is shown in Table 1.

Music was played from the beginning to the end of every class to make the classroom environment more enjoyable and relaxing for students, except for when students needed to concentrate on vocabulary tests or other similar tasks. Music played in the classroom was selected from various genres such as pop music, electronic dance music (EDM), and rock music. For years, the author had introduced students to music from various genres and collected their feedback. Thus, the author is familiar with the types of music the students like, come to like, or do not like.

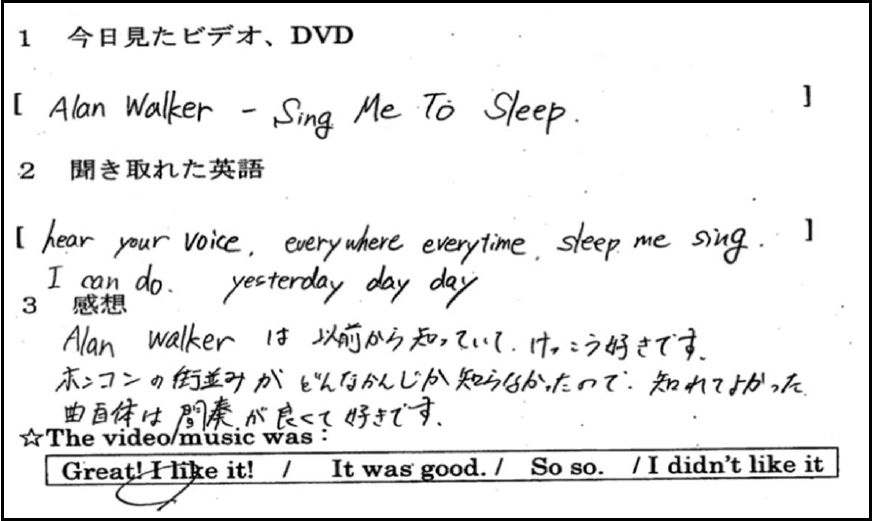

A song with an accompanying music video was also introduced at the end of every class to introduce new songs to sing or to motivate studentsŌĆÖ learning and interest in foreign cultures. In order for students to be familiar with not only English-speaking countries but also other countries where various languages are spoken, music and accompanying videos filmed in various countries, such as in Holland, Bolivia, Hong Kong, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and more, were selected. After the video, the instructor asked students to write English words or phrases they had heard and their comments on the handouts that were distributed before the video was played (as shown in Figure 1).

Singing songs in the classroom can be considered an enjoyable activity that L2 learners can appreciate (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014). However, singing songs in the classroom can also be extremely demanding, especially for students who consider themselves shy. To improve studentsŌĆÖ English pronunciation skills, though, it is of vital importance for learners to practice pronouncing words in class following a model such as an instructor or a song. Therefore, the instructor first sang the song as a demonstration, followed by students singing and performing actions such as clapping or raising their hands to reduce their sense of shyness while singing. The author found that most, if not all, of the L2 learners imitated the performance successfully by the end of the activity. The specific procedure of using songs in the classroom was as follows:

(1) The instructor distributed a handout of the lyrics after introducing the song via YouTube. The instructor also told students that they would need to practice singing the song well and to memorize the first part of the song so as to be able to write the lyrics for their listening test.

(2) In the next class, the students brought the handout and the instructor played the song while advising learners to read the words/sentences carefully.

(3) Before singing the song, the instructor provided learners with easy performance techniques using their hands, such as clapping or making gestures. This activity emphasized classroom enjoyment and classroom conformity.

(4) After practicing all the lines, the learners and the instructor sang the song together twice.

(5) The listening test for each song was held on the last day of practicing the song. The author played the song twice, during which time students needed to write part of the lyrics on answer sheets. When the test was finished, students exchanged their answer sheets and counted how many words were written correctly. The instructor then introduced learners to the next song to sing.

After the instructor gave humorous accounts of daily life while playing music with English lyrics as background music at the beginning of class, students completed a pairwork interview task. During this time, students chatted in pairs using an interview sheet on which learners recorded their partnersŌĆÖ answers. The interview sheet was created based on the pedagogical concept that language needs to be learned through meaningful interactive communication, and was thus designed to teach students how to communicate with their friends in English in real contexts. Students were encouraged to speak only in English when talking with peers, although the instructor did not try to stop them from using their L1 when it was difficult for them to communicate in English.

Students were instructed to give two presentations in front of the class on the eighth, ninth, thirteenth, and fourteenth lesson days of the semester. Giving a classroom presentation can be one of the most anxiety-provoking of language activities for L2 learners (MacIntyre & Gardner, 1991; Peng, 2014; Young, 1991). Although this task was challenging and unpredictable for students, the task was selected for the present study because several studies have suggested that speaking in front of the class is anxiety-provoking but also enjoyable (Dewaele & Dewaele, 2020; Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014). It is noted that presentations are also manageable and have the potential to even be enjoyable for learners as they are given an opportunity to overcome negative emotions such as shyness and language anxiety (Dewaele & Dewaele, 2020).

In the first presentation, the students described what they liked most in front of the audience, such as anime, drama, movies, or pets, and in the second presentation, they talked about the country they wished to visit in the future.

Before the presentations, students practiced basic English pronunciation skills in the classroom. This practice has often been neglected in Japan due to the highly prioritized university entrance examinations which, in general, do not test studentsŌĆÖ speaking ability. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that students need to acquire intelligible, if not nativelike, pronunciation for successful communication (Saito, 2012). In other words, the English pronunciation skill is the ability to be understood by interlocutors, without which L2 learners will have difficulty in communicating with others (Derwing & Munro, 2015). In this regard, this study conducted phonetic instruction in order for students to improve their L2 pronunciation, and to become confident in speaking English in front of others. The procedure of practicing English pronunciation is shown below:

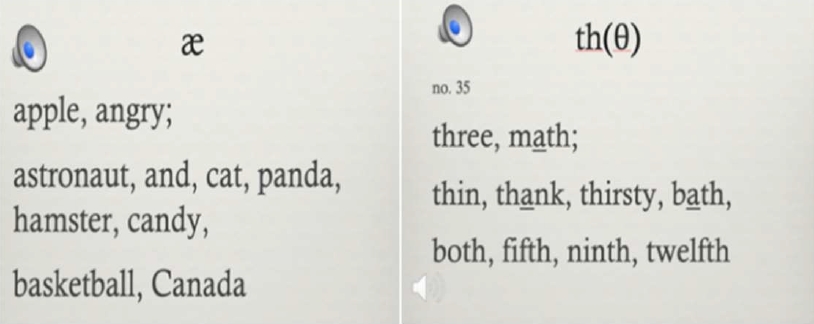

(1) The instructor first showed the students the video of BBC Learning English: Pronunciation Tips (https://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/learningenglish/grammar/pron/) on the web. The instructor told the students to understand how to pronounce phonetics, such as sounds of [r], [l], [╬Ė], [f], or [v], and to imitate the shape of the mouth (see Figure 2).

(2) The instructor showed the slides of word lists using PowerPoint. The word lists and the CD are taken from the textbook The Guidebook of Elementary School Education for Teachers edited by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT, 2009) in Japan. Sample slides used in the study is shown in Figure 3.

(3) The instructor played the sound of each English word attached on the PowerPoint, and students repeated the sound while clapping their hands along to the music originally recorded in the CD.

(4) The instructor then played pop music already attached to the PowerPoint file. Each student needed to raise their hand and read the word twice out loud.

(5) The instructor examined whether the student correctly pronounced the word or not. Since there were ten words on each slide, ten students could complete this practice before the music was automatically stopped.

This basic English pronunciation practice was conducted not only for the improvement of learnersŌĆÖ pronunciation but also for the purpose of classroom enjoyment and overcoming shyness. It was expected that by practicing English pronunciation skills, singing songs and completing pairwork activities, and conducting two presentations which most shy students wanted to avoid, they were finally able to pass ŌĆ£the river of RubiconŌĆØ (D├Črnyei, 2001, p. 88) and some, if not all, were able to feel enjoyment in having done so, even if their accomplishment was not perfect.

For quantitative analysis, surveys were conducted on the first day and on the final day of class (day 1 and day 15) in the fall semester of 2018. The questionnaire consisted of 43 items with a six-point Likert scale (from no. 1: I really donŌĆÖt think so, to no. 6: I really think so, respectively), from which 21 items were used for the present study. Two open-ended questions were also included on the first questionnaire and three were included on the final questionnaire (see Appendix). The items employed in this study were adapted from previous studies. Specifically, five items were adapted from Nishida (2013) and designed to measure intrinsic motivation, five items were adapted from McCroskey and Richmond (1982) and designed to measure shyness, and five were adapted from Nishida (2013) and Yashima (2002) and used to measure L2 WTC. Six of the items were also designed to examine student attitudes toward music. These six items were originally adopted from a scale of motivation (Tanaka, 2009) and adapted by Kitaoka (2021), where the data were shown to have moderate to high reliability. Each questionnaire took approximately five to eight minutes to complete using Google Forms in the classroom. The participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, and that their responses would not affect their course grades. The participants were also informed that the results would be used for research purposes only.

For analysis of these variables, SPSS Ver. 23 was used. Reliability estimates were calculated as CronbachŌĆÖs alpha and shown for each variable (see Table 2). The variables were normally distributed. The reliability estimates were moderate to high, which are considered reliability thresholds. The questionnaire, therefore, was regarded as a reliable measure of motivation and other variables.

Survey data from 42 students were collected by Google Forms. Data of students containing missing data or incomplete responses and mistakes from answering the questionnaire were excluded, leaving a total of 30 participants. Values of negative items (i.e., shyness) were reversed before the aggregation. To discern whether the differences found in the responses in pre- and post-data are statistically significant, data were analyzed by the paired-path dependent t-test comparison and correlation analysis. The paired-path dependent t-test comparison is generally recommended over independent t-test comparison to find the significant differences and effect sizes between pre- and post-data of participants (Takeuchi & Mizumoto, 2019). Furthermore, correlation analysis is regarded as useful and meaningful for researchers to examine the effectiveness of the methods used in the study (Spring, 2022).

The questionnaire used in quantitative analysis also included two open-ended questions regarding motivation and WTC. The questions were no. 1: ŌĆ£Please describe the reason why you are studying EnglishŌĆØ and no. 2: ŌĆ£Please describe the reasons or the situations when you are willing to speak English.ŌĆØ

StudentsŌĆÖ comments were carefully examined and run through the KH coder, following Higuchi (2016). This study used the correlational approach of content analysis and compared pre- and post-qualitative data separately to identify the differences in learnersŌĆÖ motivation before and after class. This analysis is henceforth referred to as qualitative dependent content analysis (QDCA).

First, words written by students were statistically analyzed by the KH coder. To avoid subjectivity on the part of the researcher, only the words mentioned more than twice were calculated and added to the data (Higuchi, 2016).

Second, after coding the words, the data were analyzed by cluster analysis where four to five categories were made for each result. The titles of concepts were named by the author after carefully examining the statistical data of the results. StudentsŌĆÖ comments were written originally in Japanese, then translated by the author, and finally proofread by a native speaker who majors in English education.

Table 3 presents the results of descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, t-value, and effect-size.

The results of the quantitative analysis indicate that, on average, participants were motivated intrinsically by classroom activities involving music, pairwork, and presentations [t(29) = -3.12, p = .04, r = .50], showing a large effect size. Surprisingly, there was also a large size effect on the variable of WTC [t(29) = -4.23, p = .00, r = .62], while there was no significant difference in shyness [t(29) = -1.01, p = .32, r = .19]. The results suggest that although learners enjoyed the conversations with other peers and singing songs together, it was still difficult for them to reduce their shyness in the classroom.

This quantitative result, all in all, may suggest that the use of music and other activities involving music can increase studentsŌĆÖ intrinsic motivation and enhance WTC within an environment where students can enjoy singing songs, listening to music, and watching accompanying entertaining videos. However, it seems that reducing shyness is more difficult.

PearsonŌĆÖs correlation analysis was conducted using the data of post variables. The result is shown in Table 4.

After examining the scatterplots of each correlation, PearsonŌĆÖs product-moment correlation analysis was conducted. There was a moderate positive correlation between IM and music (r = .62, p < .01), and a moderate correlation between WTC and music (r = .38, p < .05). It could be that studentsŌĆÖ intrinsic motivation may have been influenced by music and by learning about foreign countries in their own presentations. Secondly, considering the correlation analysis in shyness variables, shyness has a moderate correlation with WTC (r = .39, p < .05). This may suggest that some learners were able to speak English with their peers without feeling too much shyness. However, there was no significant correlation between shyness and other variables.

StudentsŌĆÖ comments on question no. 1: ŌĆ£Please describe the reasons why you study English below,ŌĆØ were collected and analyzed by the cluster analysis, successfully providing four clusters in both pre- and post-results, below.

Participants answered the same questions at the beginning and at the end of the semester. It is clear that answers written by learners are slightly, or broadly, in some cases, different from the previous answers. One of the unique advantages in QDCA is the ability to find a significant difference between pre- and post-qualitative data, though this approach cannot be statistically calculated to present an effect size in each case.

In the first pre-section, some of the most frequently occurring words were ŌĆ£EnglishŌĆØ (16%), ŌĆ£futureŌĆØ (13%), and ŌĆ£necessityŌĆØ (9%). It can be assumed that many students were describing their imagined use of the English language after graduation, such as in the representative comment, ŌĆ£I am not sure what I will do in the future, but I believe it will be beneficial to study English.ŌĆØ Since these students were allocated in the highest-level class, most, if not all, were motivated learners who considered learning English both beneficial and necessary. Therefore, this category was named ŌĆ£Ideal Use of English in the Future.ŌĆØ

In the post-questionnaire, some of the most frequently occurring words learners used were ŌĆ£EnglishŌĆØ (17%), ŌĆ£thinkŌĆØ (14%), ŌĆ£futureŌĆØ (12%), followed by ŌĆ£necessityŌĆØ (11%). The student who previously had commented ŌĆ£I want to work overseasŌĆØ finally commented ŌĆ£I want to work for the company that is based in overseas from Japan.ŌĆØ The student who had previously commented in the above citation ŌĆ£I am not sure what I will do in the future, but I believe it will be beneficial to study English,ŌĆØ noted in the post-section, ŌĆ£The reason to study English is that it is the most practical, and it is more fun to study than other subjects.ŌĆØ It can be argued that some students came to discern a specific reason to study English, considering it is necessary to learn English. This is partly because L2 learners may come to realize the importance of practicing English in order to succeed via their speech in front of others. Therefore, this category was named ŌĆ£Recognizing the Need for Command of English.ŌĆØ

StudentsŌĆÖ comments on question no. 2: ŌĆ£In what kind of circumstances or reasons would you like to speak English? Please write your answer below,ŌĆØ were collected and analyzed by the cluster analysis. The result of the content analysis of WTC is shown in Table 6.

Students were, all in all, interested in foreign cultures at the beginning of the class. Some of the frequent words used here were ŌĆ£overseasŌĆØ (14%), ŌĆ£EnglishŌĆØ (10%), ŌĆ£foreign countriesŌĆØ (10%), and ŌĆ£travelingŌĆØ (6%). Representative comments include ŌĆ£I want to communicate with foreignersŌĆØ and ŌĆ£To talk with friends and researchers from overseas.ŌĆØ Therefore, this category was named ŌĆ£Interest in Traveling Abroad using EnglishŌĆØ (43%).

In the post-questionnaire, learnersŌĆÖ answers changed moderately, with more responses such as ŌĆ£traveling abroadŌĆØ and ŌĆ£I want to go abroad.ŌĆØ Some of the most frequently used words were ŌĆ£overseasŌĆØ (18%), ŌĆ£EnglishŌĆØ (11%), ŌĆ£travelingŌĆØ (11%), and ŌĆ£speakingŌĆØ (8%). Students chose ŌĆ£traveling and work abroadŌĆØ as the situation where they would be mostly likely to speak English (44%). The next highest frequency category was ŌĆ£communication with peers in classŌĆØ (32%). The student who had previously answered ŌĆ£to talk with friends and researchers from overseasŌĆØ noted in the final comment the following: ŌĆ£When I talk with friends, go abroad, and in English class.ŌĆØ This change may suggest that learners had become accustomed to communicating with classmates in the classroom by completing many tasks in pairs.

The first research question addressed the relationship between motivation and music. Theorists have argued that authentic materials such as movies, music, or drama can improve learnersŌĆÖ motivation (Kadoyama, 2008). The results of this study were largely congruent with Tanaka (2009) and Garcia and Mora (2019) in that the use of authentic materials such as music was successful in motivating students and in relieving language anxiety or apprehension, provoking a wide range of emotions. However, music did not seem to help reduce shyness in this study, as the statistic result also showed there was not a significant effect in the correlation between music and shyness (r = .19). This result seems to suggest that most students remain shy mostly because they are influenced by the specific culture of Confucianism, where being silent or indirect is considered helpful toward creating harmony in society, although there have been many debates over the cultural attributes of East Asia in the literature (Ellwood & Nakane, 2009; Hsu, 2015).

In the same way that many other studies have shown that motivation is an indirect, key predictor of WTC (Peng & Woodrow, 2010; Yashima, 2002), WTC variables in the present study seem to show a correlation with learnersŌĆÖ motivation, and a moderate correlation to shyness (r = .39, p < .05). It could be pointed out that some, if not all, of the learners in the classroom were willing to communicate with other peers while reducing negative feelings, such as shyness, through classroom activities of singing songs and giving presentations.

One limitation of the present study is that it did not have a sufficient sample size (n = 30) to objectively show the effectiveness of using music in the classroom to enhance WTC and classroom enjoyment, and reduce shyness. Although recent studies show that classroom environment is the strongest direct predictor of L2 WTC (Fatemi & Choi, 2016), the conditions of feeling enjoyment are complex and there have been various discussions among researchers to clarify whether or not classroom enjoyment is beneficial to language learning (Brantmeier, 2008; Dewaele & Alfawzan, 2018; Schultz, 2012). Therefore, further research on classroom enjoyment is necessary.

Another limitation is that this study did not investigate the difference between the results of male and female students, as it has already been stated in other research studies that female learners have more positive attitudes toward language learning in general (Baker & MacIntyre, 2000; Gardner, 1985; MacIntyre et al., 2002).

This mixed-methods study aimed to find the interrelationship among shyness, motivation, and WTC, and seek ways of creating an enjoyable and effective classroom situation through music with the intention to reduce learnersŌĆÖ shyness.

To answer the first research question: ŌĆ£Can the use of music in classrooms motivate L2 learners?,ŌĆØ although there was no significant increase in music variables [t(29) = -1.96, p = .06, r = .34], there was a significant increase in motivation variables with a large effect size [t(29) = -3.12, p = .04, r= .50]. Also, correlation analyses found that there was a large, positive correlation between IM and music (r = .62, p < .01). This result reveals that the use of music in the classroom may have been functional in terms of triggering motivation of L2 learners who like music, but not to those who donŌĆÖt like music

To answer the second research question: ŌĆ£Can activities using music and a related music video reduce studentsŌĆÖ shyness?,ŌĆØ there was no significant difference in shyness from the pre- to post-test [t(29) = -1.01, p = .32, r = .19]. However, there was a moderate correlation between shyness and WTC (r = .39, p < .05). Furthermore, the qualitative analysis revealed that the word ŌĆ£shyŌĆØ was seen in the final comments (N = 2, 3%). Summatively, this suggests that though music and classroom interventions can be motivating for students, shyness might be more challenging for L2 learners to overcome.

To answer the third research question: ŌĆ£Can activities using music and a related music video enhance studentsŌĆÖ WTC?,ŌĆØ there was a significant difference with a large effect size between WTC scores on pre- and post-test [t(29) = -4.23, p = .00, r = .62]. Furthermore, because there was a moderate correlation between WTC and music (r = .38, < .05), one could claim that the inclusion in classroom activities of music and a related music video enhanced studentsŌĆÖ WTC, especially for students who like music.

In conclusion, the present study reveals that classroom activities involving music were successful in enhancing studentsŌĆÖ WTC and motivation, although it was not clear whether or not these activities were successful in reducing studentsŌĆÖ shyness. One pedagogical implication emerging from the study is that the use of music in the classroom can be an important inspiration for motivation. However, more work is required to determine the activities or interventions that can realistically reduce studentsŌĆÖ shyness.

FIGURE┬Ā1

An Example of StudentsŌĆÖ Handout Used in the Study

Note. 3. ŌĆ£I know about Alan Walker and like his music. I was glad to know what the city of Hong Kong was like. I like the interlude of the song.ŌĆØ (Trans. by author)

Table┬Ā1.

The Class Procedures

Table┬Ā2.

CronbachŌĆÖs Alpha for Each Variable

| Variables | CronbachŌĆÖs Alpha |

|---|---|

| Intrinsic Motivation | ╬▒ = .91 |

| WTC | ╬▒ = .88 |

| Shyness | ╬▒ = .88 |

| Music | ╬▒ = .85 |

Table┬Ā3.

Results of Descriptive Statistics of the Measured Variables (Paired-Path Dependent T-Test Scores)

| Pre (n = 30) | Post (n = 30) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Items | M | SD | M | SD | t | p | r | |

| IM | 5 | 22.23 | 4.58 | 24.73 | 5.10 | -3.12 | .04* | .50 |

| WTC | 5 | 15.93 | 5.45 | 20.53 | 5.08 | -4.23 | .00** | .62 |

| Shyness | 5 | 14.67 | 4.93 | 15.50 | 5.25 | -1.01 | .32 | .19 |

| Music | 6 | 23.73 | 6.37 | 26.43 | 6.42 | -1.96 | .06 | .34 |

Table┬Ā4.

Correlation Matrix of PearsonŌĆÖs Product-Moment Correlation Analysis Using Post-Class Survey

| IM | WTC | Shyness | Music | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM | - | |||

| WTC | .28 | - | ||

| Shyness | -.07 | .39* | - | |

| Music | .62** | .38* | .19 | - |

Table┬Ā5.

Results of the Content Analysis of Motivation

Table┬Ā6.

Results of the Content Analysis of WTC

REFERENCES

1. Afshan, A., Askari, I., & Manickam, L. S. S. (2015). Shyness, self-construal, extraversion-introversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism: A cross-cultural comparison among college students. SAGE Open, 5(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015587559.

2. Agawa, T., & Takeuchi, O. (2016). A new questionnaire to assess Japanese EFL learnersŌĆÖ motivation: Development and validation. ARELE: Annual Review of English Language Education in Japan, 27, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.20581/arele.27.0_1.

3. Baker, S. C., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2000). The role of gender and immersion in communication and second language orientations. Language Learning, 50(2), 311-341. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00119.

4. Brantmeier, C. (2008). Nonlinguistic variables in advanced second language reading: LearnersŌĆÖ selfŌĆÉassessment and enjoyment. Foreign Language Annals, 38, 494-504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2005.tb02516.x.

5. Carducci, B. J., & Zimbardo, P. (1995). Are you shy? Psychology Today, 64, 34-40.

6. Cheek, J. (1989). Conquering shyness. Dell.

7. Crozier, W. R. (2005). Measuring shyness: Analysis of the Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 1947-1956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.002.

8. Deci, E. L., & Gagne, M. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331-362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322.

9. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

10. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. University of Rochester Press.

11. Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. (2015). Pronunciation fundamentals: Evidence-based perspectives for L2 teaching and research, John Bbenjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/lllt.42.

12. Dewaele, J. M. (2011). Reflections on the emotional and psychological aspects of foreign language learning and use. Anglistik: International Journal of English Studies, 22(1), 23-42. https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/5096/1/Dewaele2011Anglistik.pdf.

13. Dewaele, J. M., & Alfawzan, M. (2018). Does the effect of enjoyment outweigh that of anxiety in foreign language performance? Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(1), 21-45. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.2.

14. Dewaele, J. M., & Dewaele, L. (2017). The dynamic interactions in foreign language classroom anxiety and foreign language enjoyment of pupils aged 12-18. A pseudo-longitudinal investigation. Journal of the European Second Language Association, 1(1), 12-22. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla.6.

15. Dewaele, J. M., & Dewaele, L. (2020). Are foreign language learnersŌĆÖ enjoyment and anxiety specific to the teacher? An investigation into the dynamics of learnersŌĆÖ classroom emotions. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 45-65. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2020.10.1.3.

16. Dewaele, J. M., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 237-274. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5.

17. Dewaele, J. M., Magdalena, A. F., & Saito, K. (2019). The effect of perception of teacher characteristics on Spanish EFL learnersŌĆÖ anxiety and enjoyment. The Modern Language Journal, 103(2), 412-427. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12555.

18. Dewaele, J. M., Witney, J., Saito, K., & Dewaele, L. (2018). Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: The effect of teacher and learner variables. Language Teaching Research, 22(6), 676-697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817692161.

19. D├Črnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Longman.

20. D├Črnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2009). Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. Multilingual Matters.

21. Ellwood, C., & Nakane, I. (2009). Privileging of speech in EAP and mainstream university classrooms: A critical evaluation of participation. TESOL Quarterly, 43(2), 203-230. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00165.x.

22. Fallah, N. (2014). Willingness to communicate in English, communication self-confidence, motivation, shyness and teacher immediacy among Iranian English-major undergraduates: A structural equation modeling approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 30, 140-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.12.006.

23. Fatemi, H., & Choi, C. W. (2016). Willingness to communicate in English: A microsystem model in the Iranian EFL classroom context. TESOL Quarterly, 50(1), 154-180. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.204.

24. Garcia, A. F., & Mora, M. C. F. (2019). EFL learnersŌĆÖ speaking proficiency and its connection to emotional understanding, willingness to communicate and musical experience. Language Teaching Research, 26(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819891868.

25. Gardner, R. C. (2019). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. Edward Arnold.

26. Gregersen, T. (2020). Dynamic properties of language anxiety. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 67-87. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2020.10.1.4.

27. Gregersen, T., Meza, M. D., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The motion of emotion: Idiodynamic case studies of learnersŌĆÖ foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 98(2), 574-588. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12084.

28. Griffiths, C., Oxford, R. L., Kawai, Y., Kawai, C., Park, Y. Y., Ma, X., Meng, Y., & Yang, N. (2014). Focus on context: Narratives from East Asia. System, 43, 50-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.013.

29. Higgins, L., MacIntyre, P. D., Ross, J., & Sparling, H. (2020). The terror management effects of a disaster song. Psychology of Music, 48(1), 137-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735618792404.

30. Higuchi, K. (2016). A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis: KH coder tutorial using Anne of Green Gables (Part 1). Ritsumeikan Social Sciences Review, 52(3), 77-91.

31. Horwitz, E. K., & Young, D. J. (1991). Language anxiety: From theory and research to classroom implications. Prentice Hall.

32. Hsu, W. H. (2015). Transitioning to a communication-oriented pedagogy: Taiwanese university freshmenŌĆÖs views on class participation. System, 49, 61-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.12.002.

33. Imai, Y. (2010). Emotions in SLA: New insights from collaborative learning for an EFL classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 94(2), 278-292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01021.x.

34. Kadoyama, T. (2008). Teaching communication through the use of films. ARELE, 19, 243-252. https://doi.org/10.20581/arele.19.0_243.

35. Kang, S. J. (2005). Dynamic emergence of situational willingness to communicate in a second language. System, 33, 277-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2004.10.004.

36. King, J. (2013). Silence in the second language classroom. Palgrave Macmillan.

37. Kitaoka, K. (2021). An empirical study of classroom enjoyment and negative emotions: A model of the use of authentic materials in the Japanese EFL context. ATEM Journal, 26, 87-100.

38. Kormos, J., Kiddle, T., & Csiźer, K. (2011). Systems of goals, attitudes, and self-related beliefs in second-languagelearning motivation. Applied Linguistics, 32(5), 495-516. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amr019.

39. Larsen-Freeman, D. (1985). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford University Press.

40. MacIntyre, P. D., Dörnyei, Z., Clément, R., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal, 82, 545-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x.

41. MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: A review of literature for language teachers. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign Language and second language learning (pp. 24-43). McGraw-Hill Education.

42. MacIntyre, P. D., Clément, R., & Donovan, L. A. (2002). Sex and age effects on willingness to communicate, anxiety, perceived competence, and L2 motivation among junior high school French immersion students. Language Learning, 52(3), 537-564. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00226.

43. MacIntyre, P. D., & Gardner, R. C. (1991). Methods and results in the study of anxiety and language learning: A review of the literature. Language Learning, 41(1), 85-117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1991.tb00677.x.

44. MacIntyre, P. D., Potter, G. K., & Burns, J. N. (2012). The socio-educational model of music motivation. Journal of Research in Music Education, 60(2), 129-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429412444609.

45. Maley, A. (1987). Poetry and song as effective language-learning activities. In W. Rivers (Ed.), Interactive language teaching (pp. 93-109). Cambridge University Press.

46. McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1982). Communication apprehension and shyness: Conceptual and operational distinctions. Central States Speech Journal, 33, 458-468. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510978209388452.

47. MEXT. (Ed.). (2009). Shougakkou gaikokugokatsudo kenshu gaidobukku [The guidebook of elementary school education for teachers]. Obunsha.

48. Nishida, R. (2013). The L2 self, motivation, international posture, willingness to communicate and can-do among Japanese university learners of English. Language Education & Technology, 50, 43-67. https://doi.org/10.24539/let.50.0_43.

49. Noels, K. A., Clément, R., & Pelletier, L. G. (1999). Perceptions of teachersŌĆÖ communicative style and studentsŌĆÖ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 83(1), 23-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00003.

50. Peng, J. E. (2014). Willingness to communicate in the Chinese EFL university classroom: An ecological perspective. Multilingual Matters.

51. Peng, J. E., & Woodrow, L. (2010). Willingness to communicate in English: A model in the Chinese EFL classroom context. Language Learning, 60, 834-876. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00576.x.

52. Pilkonis, P. A. (1977). The behavioral consequences of shyness. Journal of Personality, 45(4), 596-611. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1977.tb00174.x.

53. Saito, K. (2012). Effects of instruction on L2 pronunciation development: A synthesis of 15 quasi-experimental intervention studies. TESOL, 46(4), 842-854. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.67.

54. Saito, K., Dewaele, J. M., Abe, M., & In’nami, Y. (2018). Motivation, emotion, learning experience and second language comprehensibility development in classroom settings: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Language Learning, 68(3), 709-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12297.

55. Schultz, L. M. (2012). Affect with Chinese learners of English: Enjoyment, self-perception, self-assessment, and abilities across level of language learning. Quarterly Journal of Chinese Studies, 5(2), 65-81.

56. Sette, S., Baldwin, D., Zava, F., & Baumgartner, E. (2019). Shame on me? Shyness, social experiences at preschool, and young childrenŌĆÖs self-conscious emotions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 229-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.12.012.

57. Spring, R. (2022). Free, online multilingual statistics for linguistics and language education researchers. Center for

Culture and Language Education, Tohoku University Nenpo, 8, 32-38. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12037.63202.

58. Takeuchi, O., & Mizumoto, A. (Eds.). (2019). Gaikokugo Kyoiku Handobukku (4th ed.) [Handbook of foreign language education research]. Shohakusha.

59. Tanaka, H. (2009). Mittsuno reberunonaihatuteki doukidukewo takameru: Doukidukewo takameruhouryakuno koukakennsho [Enhancing intrinsic motivation at three levels: The Effects of motivational strategies]. JALT Journal, 31(2), 227-250. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTJJ36.1-5.

60. Teimouri, Y. (2017). L2 selves, emotions, and motivated behaviours. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 39, 681-709. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263116000243.

61. Ueki, M., & Takeuchi, O. (2015). Study abroad and motivation to learn a second language: Exploring the possibility of the L2 motivational self-system. Language Education & Technology, 52, 1-25.

62. Weaver, C. (2005). Using the Rasch model to develop a measure of second language learnersŌĆÖ willingness to communicate within a language classroom. Journal of Applied Measurement, 6(4), 396-415.

63. Yashima, T. (2002). Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. The Modern Language Journal, 86(1), 54-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00136.

64. Yashima, T., MacIntyre, P. D., & Ikeda, M. (2018). Situated willingness to communicate in an L2: Interplay of individual characteristics and context. Language Teaching Research, 22(1), 115-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816657851.

65. Yashima, T., Noels, K. A., Shizuka, T., Takeuchi, O., Yamane, S., & Yoshizawa, K. (2009). The interplay of classroom anxiety, intrinsic motivation, and gender in the Japanese EFL context. Journal of Foreign Language Education and Research, 17, 41-64. http://hdl.handle.net/10112/768.

66. Young, D. J. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does language anxiety research suggest? The Modern Language Journal, 75, 426-439. https://doi.org/10.2307/329492.

Appendices

APPENDIX

Questionnaire Used in The Study With Their English Translations (by Author)

(The survey is modified from the questionnaire used for the study to focus on targeted variables)

stem-2023-24-1-55-app1.pdf

- TOOLS

- FOR CONTRIBUTORS

-

- For Authors

- Instructions for authors

- Regulations for submission

- AuthorŌĆÖs checklist

- Copyright transfer agreement and Declaration of ethical conduct in research

- Conflict of Interest Disclosure Form

- Disclosure Form for People with Personal Connections

- E-submission

- For Reviewers

- Instructions for reviewers

- How to become a reviewer

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print